From the Editor: Fed Up!

IsumaTV’s First Annual Online Film Festival

Paving over Cultural Identity

Retracing Twenty-Five Year Old Foot and Paw Steps

Okpik’s Dream Update

Bannock – On the Frozen Sea, in the Woods or at Home

Media Review: Romance of the Far Fur Country

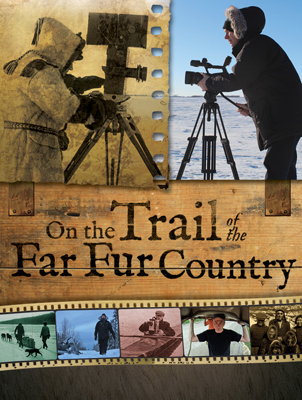

Media Review: On the Trail of the Far Fur Country

IMHO: Truth, History and Dogs

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

It is an understatement to simply say that the movie On the Trail of the Far Fur Country, completed and released in 2014 is a companion movie to The Romance of the Far Fur Country (sometimes referred to in this review as the original movie). To state that the two movies are complementary, while certainly very true, is also an understatement. On the Trail of the Far Fur Country offers much more than just an explanation of how and why the original movie was made and it provides much new information. On the Trail of the Far Fur Country bravely grabs hold of the many social, cultural, political and ecological issues that leap out from The Romance of the Far Fur Country and addresses them, but with a refreshing sensitivity and subtlety.

Perhaps the word sensitive summarizes the whole “tone” of this movie. From the soft and insightful narration, the musical score, even to the grippingly emotional visual images of members of Inuit and First Nations communities seeing their grandparents and great aunts and uncles come alive before their very eyes….“It’s really touching to know what he looked like.” There is a softness to the dialogue. Even the most vocal critics of past paternalism and abuse were able to state that “there were good guys in there too, even the missionaries had the best of intentions…but they did damage to the culture.”

This sensitivity is very evident in the videography. The scenes before us move effortlessly from 1919 to 2014, from stark black and white to colour and then back again. In some scenes the characters literally do “come alive”, in sync with the words that are being spoken by those people who are viewing the footage on a hand held tablet…“It would be nice to go back for five minutes and talk to the ancestors.”

In On the Trail of the Far Fur Country, effort was made to re-create or at least to revisit visual images from the original movie. The rocks that comprised the dock in Kimmirut harbour in 1919 are still there, right next to the more modern manufactured dock that has replaced it. Many of the original HBC buildings are still in place. In Fort Chipewyan, while many of the original HBC post buildings are gone or have been scattered around the community, the videographer does take us right back to the site of the original HBC Fur Trade Post, with the same panoramic view of Lake Athabasca that was part of the 1919 film. In Moose Factory, a trading post that was established by the HBC in 1673, we are taken back to the original site, the whole fur trade infrastructure – the warehouses, residences, stores and docks – has disappeared. In some cases the contrasts are jolting. This is particularly true of the scenes, past and present, of Fort McMurray. But then virtually the whole country has been numbed by the changes taking place in the Athabasca Tar Sands.

Those behind the making of this movie are to be loudly commended. Those who had the foresight to make this movie were inspired. While it does follow the travelogue format that was featured in The Romance of the Far Fur Country, it is much more. It is a true documentary. Lots of footage from The Romance of the Far Fur Country is included, but it doesn’t rigidly follow the sequence of the original storyline. Footage is often used out of the original context to illustrate some important aspects of the original movie or to illustrate one of the many issues that have been spawned by the original movie. There is also historic footage from sources other than The Romance of the Far Fur Country. It is understood that photographer Harold Wyckoff actually shot eighteen hours of footage and no doubt some of the “new” footage in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country is from some of the original footage that ended up on the cutting room floor. In addition, there is footage that clearly seems to be from other sources, most likely the HBC 250 Year Anniversary Pageant celebrations.

This reviewer is comfortable stating that there is no question that it makes complete sense to view the original movie before watching On the Trail of the Far Fur Country. This writer experienced very different emotions while watching each. The experience of watching The Romance of the Far Fur Country was like a discovery and a wonderful escape into a special world. It was like receiving a very special gift to be treasured, and safeguarded. The experience of watching On the Trail of the Far Fur Country was exciting but exhausting, as this viewer worked hard to make sense of the “pieces” of the larger picture that had now been presented by both movies.

Watching On the Trail of the Far Fur Country will add a great deal to the viewer’s comprehension of the many historical and logistical issues that influenced the “shape” of the original movie. There are little things. For example in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country there is “new” footage that wasn’t part of The Romance of the Far Fur Country. A panoramic shot of Kimmirut reveals that indeed there was a small church already standing in 1919, and there are scenes of a church service being held outside this building. The church did have an early presence in that community after all. This in turn suggests that changes to a traditional Inuit way of life were probably further advanced than this writer first thought. And after viewing On the Trail of the Far Fur Country, it is clear that the Nascopie didn’t off-load all of the supplies for the lower James Bay area at Charlton Island. The vessel went all the way to Moose Factory and, with the benefit of hindsight, why wouldn’t it? HBC vessels had been sailing to that spot since 1673.

While viewing The Romance of the Far Fur Country, this reviewer wrestled with some very basic questions. I was hoping that viewing On the Trail of the Far Fur Country would help me to come up with answers.

Why was The Romance of the Far Fur Country made? The bland response is that the HBC wanted to celebrate the fact that this incredibly successful company was, in 1920, 250 years-old. We all like to mark milestones, often with a celebration. Surely the HBC wanted to accomplish this by creating something that was truly unique for its era. A blockbuster mega-movie would build on the public’s enchantment and fascination with a new medium, and it would draw as much public awareness as possible to the Company, no doubt with the hope that this would engender even more (financial) success in the future. Is this cynicism justified?

Making the original movie required a lot of arduous work, particularly when it came to documenting the activity of the trapper on the trap line. The logistics of travel alone are mindboggling. On one hand you have to admire people like Wyckoff who “…see beauty and grandeur, others see discomfort. I can’t tear myself away from good photographic subjects.” While there were others, like his filming assistant Bill Deer, who it would appear couldn’t wait to leave the expedition when offered the chance to do so in Winnipeg. There are the self deprecating jokes like “now you can realize why the HBC has had a monopoly of the fur trade for so many years….no one else would want it.” It was tough work and the HBC seemed to believe that if it wasn’t physically demanding then it probably meant you weren’t working hard enough. Certainly this theme comes through repeatedly when one reads autobiographies written by HBC fur traders. It is almost as though the HBC knew no other way to do things.

In January 1920 in Fort Chipewyan filming was completed and in May 1920, when the movie was premiered, it “flaunted the romance of the expedition and the Company’s history.” Was this really romantic?

Who was the intended target audience for The Romance of the Far Fur Country? It may be difficult to place ourselves into the shoes of the 1919 viewing audience. Public perceptions, attitudes and opinions change with time. There is good reason to believe however that the fur trade was perceived very differently in 1919 than it is now, and that the public was indeed attracted by a way of life seen to be adventurous, exciting, emancipating and indeed romantic. The literature from this era suggests this as do biographical accounts of actual fur traders, many of them working for the HBC. Jack London’s Call of the Wild, written in 1903 (and which is still in print, over 5 million copies later), had a “freeing” impact on a whole generation. It is also no accident that the intertitles of The Romance of the Far Fur Country include quotations from the writings of Robert Service.

Interest in The Romance of the Far Fur Country, however, was apparently short-lived. Possibly in an attempt to prolong its life span, more than one version of the final movie was produced, one for North American audiences and one for English audiences. Also, the full movie was made into a number of shorter movies, possibly to appeal to those with very specific interests or to those who might not be interested in sitting through two hours of trees and rocks and rocks and trees and trees and rocks…….

In 2015 the majority of viewers are most likely viewing The Romance of the Far Fur Country through the eyes of someone interested in the history of the North, the fur trade and possibly the HBC. In addition they may also be looking at this movie through the eyes of someone who is trying to set into perspective the unfolding history of the past, almost 100 years of Canadian, Northern, First Nations, Fur Trade and HBC history. This audience was not anticipated by the original filmmakers. However the footage is now an invaluable historical document.

In On the Trail of the Far Fur Country there are scenes of present-day trapping in Fort McMurray that will no doubt lead to some angry letters to the editor. It is my belief that those responsible for making this movie hoped these trapping scenes might lead to some earnest discussion. Almost one hundred years after the making of The Romance of the Far Fur Country, public attitudes toward many things have changed. The HBC’s shift towards developing larger retail sales outlets, as clearly shown in The Romance of the Far Fur Country was an indication that even in 1919, public attitudes toward wearing furs was changing.

The Fort McMurray trapper is an amiable but no-nonsense individual who talks very matter-of-factly about the business of fur trapping. He seems to be a very knowledgeable trapper. He tells us that his trap line is actually located along cut lines that were bulldozed through the bush by the oil companies as part of their exploration process in pursuit of oil-bearing bitumen and that this has saved him a lot of work, making it easier to get around. I am struck by the similarities between the actions of this trapper and those of the workers in the Oil Sands, both extracting a valuable resource. The trapper could argue that he is harvesting a renewable and non-polluting resource, but so were the whalers that have driven the world’s whale population to the point of extinction and so were the buffalo hunters in what is now present-day Wood Buffalo National Park which necessitated the imposition of hunting restrictions at a time when the First Nations people in Fort Chipewyan were dependent on that meat as a source of food. There is also the question of the impact of all types of resource extraction on animal habitat which has led to the near extinction of the Mountain Caribou in British Columbia.

What was the message or story that the HBC wanted to deliver in the Romance movie? The narrator of On the Trail of the Far Fur Country infers that the intent of the original movie was to tell the story of the “great and romantic history of the fur trade” and that if there were any problems or fallout from this approach, they weren’t important, “they were just footnotes.”

The makers of On the Trail of the Far Fur Country, however, do not avoid the reality that the original movie clearly highlights: significant social and cultural issues (and in some cases the very origins of these social issues) that continue to pre-occupy First Nations, Inuit and non-native Canadians today. These issues include the paternalistic attitude and assimilation policies of the major non-native players in the Canadian North, starting with the fur trade companies, the national government, and the churches; the tragic legacy of the residential schools; the whole issue of Native sovereignty; in a few cases the impact of the treaty process and the dramatic shifts in lifestyle and the associated loss of culture and significant ecological/environmental concerns. It is for these reasons that this movie is much more than just another travelogue.

The creators of On the Trail of the Far Fur Country chose Native spokespersons who were particularly vocal and articulate about these issues. It was moving to observe modern Inuit spokespersons viewing the footage of their First Nations sisters and brothers, people that they certainly didn’t know and who were alive almost 100 years ago, but recognizing as they viewed on tablets the footage from The Romance of the Far Fur Country that both groups were dealing with the exact same social, legal and cultural issues and their impact on their way of life. To quote one Inuit woman commenting on the words of a Chipewyan Chief, “I felt proud in that moment that he would stand up and say that.”

How did the creators of The Romance of the Far Fur Country deliver this message? It appears clear to this reviewer that after the arduous canoe poling trip upstream, against the strong current of the Abitibi River from Moose Factory to Cochrane Ontario, the original moviemakers (and there weren’t many of them: photographer Harold Wyckoff, his assistant Bill Deer and Captain Edmund Mack) realized that their movie was lacking some punch so they made some significant changes to their original plans. While this may have been in the works all along, Captain Mack was replaced by Captain Thomas O’Kelly (the Factor), who becomes the “star” of the movie, clearly tying things together for the rest of the film. We are told in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country about another change, the decision to travel north to the HBC stronghold of Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca. The original plans had apparently been to travel to The Pas in northern Manitoba.

It isn’t clear just when a decision was made to travel to Alert Bay on tiny Cormorant Island off of the eastern coast of Vancouver Island, even though there was no significant HBC connection with this location. The closest HBC post was Fort Rupert which was established near the present day community of Port Hardy on the east coast of Vancouver Island in 1846.

No doubt the decision to travel to Alert Bay was one made to capitalize on the world’s infatuation with the culture of the Kwakwaka‘wakw people of this area, with the hope that this would create yet another reason why the general public would want to view the original movie. In 1914 Edward S. Curtis made a film based in Alert Bay that was a melodrama with an all First Nations cast. There was a worldwide fascination with the artistically rich and intact West Coast culture of this First Nation.

Just why they felt there was a need to regroup at this point is a matter of speculation. The fact is that photographer Harold Wyckoff did a fantastic job and he captured priceless footage. Given the unwieldy equipment at his disposal, the unforgiving landscape within which he had to work, the harsh weather conditions, we are all beholden to Wyckoff for creating a historic document and for giving us the footage that it is now our privilege to view and appreciate. While Wyckoff was the photographer, he was also expected to develop the storyline, literally as he was recording whatever it was that he was filming at the time. This was a herculean task and the end result was that while the footage of the ever-changing landscape was interesting, it was not everyone’s cup of tea, and unless something more could be added to the finished product, it might not prove to be the success that was envisaged.

Another result of the decision to shift direction in “mid-movie” and to travel to Alert Bay and Fort Chipewyan was that the moviemakers essentially ran out of time. Their travel was completely dependent on the weather and when they arrived at Athabasca Landing to begin the journey down the Athabasca River to Lake Athabasca and Fort Chipewyan, the water levels were too low for river travel. It becomes quite evident, winter had arrived. The urgency of their precarious situation is well developed in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country. It is now clear that the makers of The Romance of the Far Fur Country deserve one big HBC medal for making that movie happen, and for filming even as one calamity after another was unfolding. They actually turned the desperate journey along the upper Athabasca River into a pretty exciting bit of footage.

The footage from Alert Bay highlights a very poignant legacy of the making of The Romance of the Far Fur Country and one that will provide the basis for much future discussion. It is impossible to watch this movie in 2015 without setting the scenes into the perspective that almost a century of change offers the present-day viewer. In 1919, the photographer went out of his way to highlight the fact that in 1885 the Potlatch Ceremony had been banned among all First Nations, particularly the Kwakwaka’wakw people of Alert Bay, by the national government. There is now a widespread belief that this was a government decision designed to eliminate all First Nations culture and to “take the Indian out of the Indian.” We are told that Captain O’Kelly went to great lengths to negotiate the scene for The Romance of the Far Fur Country where four young men wore the banned Potlatch regalia for the camera, demonstrating that while “officially” forbidden, the Potlatch was alive and well and underground. Was this scene an act of sensationalism designed to stimulate the interest of the viewing public or was O’Kelly making a defiant statement that the banning of the Potlatch was not acceptable? No matter what, it was a clear public statement. The ban was not rescinded by the Canadian government until 1951.

This is but one example of what later viewers would perceive to be a significant example of cultural injustice. In hindsight, it is now possible to see in The Romance of the Far Fur Country other indicators of the significant and very negative changes that were in store for a vibrant First Nations way of life.

One small vignette in The Romance of the Far Fur Country proudly features the “well scrubbed” children of the Alert Bay Girls’ Home. This same vignette is re-visited in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country where it is pointed out that one of the young girls makes a defiant “smirk” at the camera as she walks by. The Girls’ Home was a precursor to St. Michael’s Indian Residential School which opened in 1922. Ninety-five years later, the dark legacy of the Indian Residential Schools is now only too evident throughout Canada, which has just been through a painful yet uplifting process of Recognition, Apology, Reconciliation and Healing for everyone, but particularly for the survivors of Canadian Residential Schools. As On the Trail of the Far Fur Country shifts its focus to Alert Bay, one of the first images that comes into view is a large red brick building. This was St. Michael’s which had been sitting empty and crumbling since 1975, after 8,000 First Nations children had passed through its doors. Perhaps it is very significant that the film then examines the decaying remains of the “smirk” and the “frown” house poles, which had been moved to the site of St. Michael’s from their original location. They had been featured in The Romance of the Far Fur Country as the proud thunderbird house poles in front of the very impressive Great Hall with the huge opening beak entranceway. On February 18, 2015, the community of Alert Bay, members of the ’Namgis First Nation and First Nations and non-First Nations people everywhere celebrated the demolition of St. Michael’s.

Please allow me one indulgence. I have to make mention of a very magical scene in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country. It relates to the history of the use of working sled dogs in the North, which is the primary reason that I have been so drawn to these movies. Robert Grandjambe is a First Nations dog musher/kennel owner who resides in Fort Chipewyan. His dogs appear in On the Trail of the Far Fur Country. He raises dogs that look very much like the Mackenzie River Huskies featured throughout The Romance of the Far Fur Country.

Robert runs his dogs in a very traditional manner. Using padded leather collar harness the dogs are run in single file in what is called a tandem hook-up because each harness has two (tandem) leather traces that run down each side of the dog and which are fastened to the harness of the dog running immediately behind. The dogs are fitted out with brightly coloured and embroidered dog blankets or “tapis”, which fit over the dog’s back and are fastened to the back pad of the harness. In addition, the dogs have brightly coloured collar horns made of wool and ribbons, which are fastened to the tops of the padded collars on the harness. There may also be some bells fastened to the harness.

The dogs are hitched to an oak toboggan sixteen inches wide, has eight feet of contact with the snow and has a beautifully rounded, completely symmetrical curl or “hood” at the front of the toboggan. The wooden handlebar is ingeniously fastened to the toboggan itself with the use of ropes. The tension of the ropes keeps the handlebar in place but nothing is rigidly bolted so that as the toboggan flexes everything moves and nothing breaks. The toboggan is fitted with a canvas wrapper or “carry-all” capable of carrying a huge load.

Robert wears an embroidered jacket made of a heavy wool duffel or stroud fabric complete with fringes. He also wears a pair of very rare leggings, also made of a heavy wool fabric, and of course moose hide moccasins with duffel liners. It is obvious that for Robert running dogs is more than just mushing. He is also living mushing's history.

In the On the Trail of the Far Fur Country there is a scene that begins with some black and white footage taken from The Romance of the Far Fur Country of a dog team moving away from the camera. The photographer is filming from the back of the team. At some point this dog team becomes Robert’s dog team, still in black and white and still moving away from the photographer. Slowly this scene of the moving dog team transitions into full colour. It is one of the most beautiful scenes of a moving dog team that you will ever see. While very common at the time that The Romance of the Far Fur Country was made, this scene has now disappeared, except as a well-staged act of living history.

Both The Romance of the Far Fur Country and On the Trail of the Far Fur Country are now available through the Winnipeg Film Group. Get one individually, or as a combo pack. For the restored 1920 film, this is a special double disc region free DVD packed with extras: approximately six hours of video content. A heads up for collectors, archivists, teachers, cinephiles and fur trade history lovers out there, this is a limited edition.

Ed. Two of Jeff Dinsdale’s many passions are sled dog and polar history. Enjoy more of these accounts on his Mushing Past blog. He is also one of the organizers of the annual Gold Rush Sled Dog Mail Run. Jeff and his family live in British Columbia where for a very long time he has raised and traveled with Inuit Dogs.