Table of Contents

*

Raising Sled Dogs

*

The Good, the Bad and the ‘Eskimo’ Dog

*

The Russian Connection

*

Honoured Symbol Under Fire

*

Iqaluit Team Owner Speaks Out

*

The Homecoming

*

Niels Pedersen, D.V.M:

Challenging Folk Remedies

*

Janice Howls:

Maintaining the ISD Roots

*

Book Review:

Portrait of Antarctica

*

First Hand Account:

Exploration of Antarctica

*

IMHO:

Dog Ownership in Modern Society

*

Baking: Carnivore Brownies

*

Behaviour Notebook:

Silent and Induced Heat

*

ISDI Summit Postponed

*

Memorable Inuit Dog Encounters

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The Fan

Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

by Isaija Atagutsiaq

A poorly treated dog is thin and has a

sad appearance, but

a well cared for dog is fat, healthy and

appears happy.

In the past dogs were our only source of power and we relied on them for transportation. Sled dogs were raised from birth. Each female was different; some were good for breeding and some were not. A man with a good sized dog team was able to find out which of his females produced the best sled dogs, and he would use her just for breeding. Others would have puppies too, but they would not be bred. That's how sled dogs were raised.

Puppies were cared for as soon as they were born. The owner tried to make sure the mother had plenty to eat so her puppies would be fat and healthy. If a breeding female isn't fed well her puppies will be skinny and small, and will never grow to full size. If a man wants to have strong full grown dogs he has to look after them very well.

Once the puppies were weaned, they were trained to eat only what they were offered. Being dogs, they would of course roam around looking for food, but the owner tried to train them not to eat meat left lying around. When it was time for the dogs to eat, the owner would call them and gather them together, and then feed them. This was the way it was done, and some men had very fine dogs as a result. Other men, though they seemed well off and important, nevertheless had poor dogs - skinny and very small.

When puppies are growing up they should not be punished every time they do something wrong. A badly beaten dog never learns to obey and will not respond when scolded. A dog that has not been punished too much will stop disobeying immediately when spoke to sharply. In this way dogs were trained to know the difference between what was allowed and what was not.

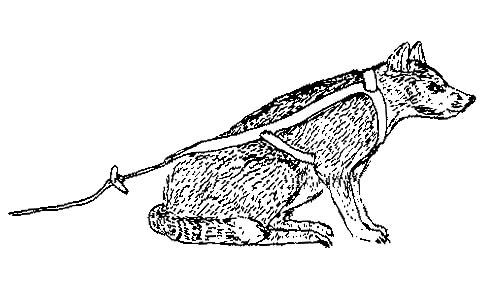

This dog is frequently beaten. It is

not really sitting but

is instead cowering, afraid of being

struck again. Drawn

by Francois Quassa.

When a young dog was old enough to be trained to pull a qamutik, it was added to the team. Again, as the dog learns to pull properly it should not be punished severely if the owner wants it to learn to work hard and obey.

We also tried to train our team to recognize tone of voice. When hunting caribou or polar bear we would speak very quietly, in order not to be heard by the animals. A badly treated dogteam will never learn to pay attention to a change in tone of voice, but a well trained team will be alert and ready, knowing something is about to happen. They will give full attention to whatever they are commanded to do. That is how we were advised to train our dogteam, by teaching them all kinds of things.

Whips are a part of the equipment used for a dogteam, but they must not be overused. Whipping dogs unmercifully will only harden them physically and mentally and then, if the owner uses his whip to signal the team to go faster, they will be confused and wont respond. Teams that have not been terrorized respond to whip signals very well, but dogs that live in fear of the whip never learn to obey.

Dogs were also trained for polar bear hunting, for which they are very useful. When a polar bear is sighted, the dogs must remain calm, and if the owner tells them to follow or not follow it is essential that they respond well. When the dogs become accustomed to polar bear hunting they should never be given a false alarm. If they are teased and told a polar bear is nearby, they will at first believe it and get excited; but after having been teased that way more than once or twice, they will never believe what their owner tells them, even when there actually is a polar bear nearby.

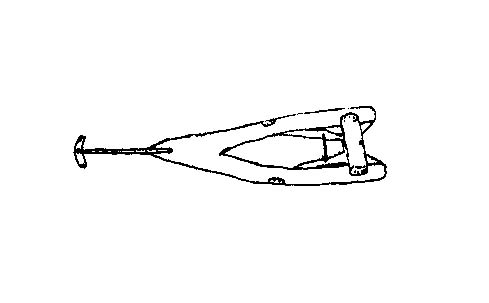

The harness as seen from the top.

In summertime people used to walk inland for weeks to hunt caribou, and they always brought dogs along. A man would choose some of his dogs and the dogs would know whether he wanted them to follow or not. Their behavior then depended on the quality of their training, and badly trained ones would try to come along even though they were not supposed to. There were a few well trained teams that would do exactly what their owner told them.

In those days humans and dogs were always helping each other, and the dogs were extremely useful. They pulled the qamutik in winter, and in the summer they carried meat, tents and other equipment in special packs. When used for hunting, either in summer or winter, they were always put on a leash. Dogs had to be well trained to hunt caribou or polar bear.

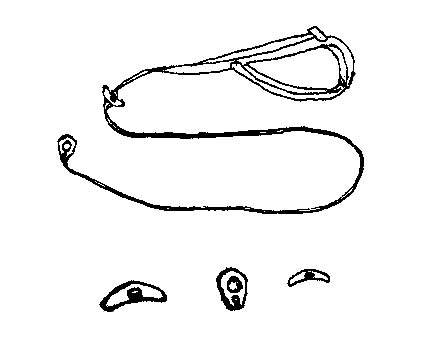

The dog harness is fastened to the

trace with a

closer view of the fastening ring and

toggles.

Drawn by Francois Quassa.

Each trace should have a fastening ring (uqsiq). If a loop is tied in the trace instead, it will be difficult to unhook. Each trace should also have a toggle (sanniruujaq) attaching the trace to the harness. This is because it is easier, when hunting polar bears or feeding the dogs while traveling, simply to unhook the toggle instead of having to unharness the dogs. We tried to make every thing convenient for all situations. When a hunter sights a polar bear unexpectedly, he can unhitch the dogs quickly and easily by unhooking the toggles. If there were no toggles and the traces were tied to the harnesses, the traces would have to be cut if a polar bear were nearby, and we would never want to cut the traces. Toggles also save time, enabling the hunter to release the dogs without having to remove the harnesses, later having to put them back on. The toggle is positioned at the end of the harness so the dogs can move freely while attacking the polar bear, for otherwise, if the traces were still attached to the harness, they would all get tangled.

There were men who had very fine dog teams and others who didn't. We were advised how to train our dogs properly and we learned a great deal. In the past, we used them well, but nowadays they are no longer used as much. I have not told this story from what I have heard, but instead I have told it from my own experience. I understand dogs very well because I used them myself.

This story originally appeared in the #73 (1991) issue of Inuktitut Magazine, which retains exclusive copyright. We are grateful to the magazine for granting us permission to reprint it here. Inuktitut Magazine is the national cultural and educational magazine which documents oral history and knowledge of Canadian Inuit. The magazine publishes the work of Inuit writers, photographers and artists, and also encourages cultural exchange among Canadian Inuit communities, and promotes Inuktitut language literacy. It is now published bi-annually in two versions, the northern version containing syllabics, standard orthography and English, and the southern version replacing the standard orthography with French. The broad range of topics covered is an excellent resource for a large number of subject areas: current affairs, native studies, French immersion, language and linguistics, geography, social studies, and ethnic literature. Inuktitut presents excellent information on past and current Inuit culture and life, which cannot be obtained anywhere else. The price is $28.00 CAD by check, Visa or Master Card. Please indicate your preference for either the northern or the southern version.

Contact information:

Inuit Tapirisat of Canada

510-170 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa ON K1P 5V5

(613) 238-8181 ext. 228

(613) 234-1991 fax