In this Post

From the

Editor: The Art of Storytelling

Driving Dogs During the Golden Era of Antarctic Exploration

A Bridge of Ice

Book Review: Burnt Snow

“Arctic-adapted dogs emerged at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition”

QIMMEQ research paper podcast

New payment option: Ken MacRury’s master’s thesis

Driving Dogs During the Golden Era of Antarctic Exploration

A Bridge of Ice

Book Review: Burnt Snow

“Arctic-adapted dogs emerged at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition”

QIMMEQ research paper podcast

New payment option: Ken MacRury’s master’s thesis

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor's/Publisher's

Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch Website and

Publications of the Inuit Sled Dog– the

quarterly Journal (retired

in 2018) and PostScript – are dedicated to the aboriginal

landrace traditional Inuit Sled Dog as well as

related Inuit culture and traditions.

PostScript is

published intermittently as

material becomes available. Online access is

free at: https://thefanhitch.org.

PostScript welcomes your

letters, stories, comments and suggestions.

The editorial staff reserves the right to

edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

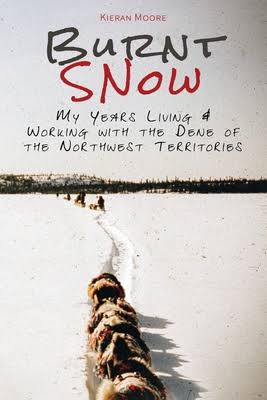

Burnt Snow: My years living & working with the Dene of the Northwest Territories

by Kieran Moore

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

I met Kieran Moore in November 2005 at the annual Snow Walker’s Rendezvous in Fairlee, Vermont. A first time attendee to this three-day gathering, he was a first time presenter as well. Moore was introduced to the audience described as a “true Irish seanchaí” (anglicized as “shanachie“), the Gaelic word for storyteller.

The other speakers’ offerings that weekend were accompanied by visual aids remotely operated at the podium – either a slide projector or a bells and whistles Power Point program of still images or videos accompanied by music, and often a combination of all that. Moore, on the other hand, didn’t walk to the podium at the front of the room. He stood in the aisle in between the two sides of the audience, towards the back a little, carrying some notes and a few printed clear plastic sheets to display using an opaque projector. Looking back I could describe Moore’s visual aids as old-tech, but I remember subsequent years when he was asked to speak again (and again) where he even went no-tech. The old adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words” did not apply to Moore. The saying “Less is more” did. This seanchaí didn’t necessarily need much, if any, in the way of visual aids.

For the rest of the weekend and for the subsequent years Moore returned to tell his stories, his appreciative audience prodded, “When are you gonna write a book? You’ve gotta write a book!”

Fifteen years later, August 2020, Burnt Snow: My years living & working with the Dene of the Northwest Territories by Kieran Moore was finally published.

Moore’s printed words offer the same captivating style that enthralled his listeners at the Snow Walker’s Rendezvous. Storytelling is an art form and this Irish seanchaí ranks right up there with top notch raconteurs the likes of Jean Shepherd, Daniel Pinkwater and even Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain).

The tradition of storytelling was an integral part of the Dene way, and I learned a great deal by listening and sharing in that tradition. These stories I tell here reflect the level of my personal engagement with them. These stories are told in the spirit of the storytelling tradition of the Dene and that of my Irish ancestors. (“Introduction” page 1)In January 1971 a restless young Irish immigrant living in Winnipeg, Manitoba headed north seeking purpose to his life and found it in the wilds of Canada’s Northwest Territories. There he met the Dene (pronounced den-A). This was a period of time on the cusp of enormous transition for these First Nations people. Moore was not just a witness. Welcomed into Dene society, he embraced their culture and all manners of their subsistence lifestyle, coming to understand and respect them as few other outsiders could or wanted to. When necessary, he fiercely defended Dene rights when they were threatened. On one occasion in particular, heartbreaking consequences were the result of Moore’s support.

Because he sought out anyone who would tell him stories, the scores of positive responses he received resulted in his documentation of the Dene’s rich culture. During one such personal encounter Moore wrote:

The woman sat in a corner with a young girl by her side, who acted as a translator…she began her story, “I know most of you have heard all the legends about Edzo. I have a story about him that has never been told. I am getting old and feel it is time for me to pass the story on.” Then she directed the following comment to me. “This story is for you to pass it on to others. This will now be your story to tell.” (“A Gifted Story” page 69)Moore also details arduous dog team travel, some under horrific conditions. One tale in particular describes a dog in his team that appeared to drop dead in harness. Not breathing, he could not be revived even with mouth-to-nose resuscitation. Lightly buried in a snow bank so his remains might be of use to wild animals, the group of hunters and their dog teams returned to their home village after the long and exhausting search for food. The next day that very dog was seen coming off the frozen lake and trotting back into the community!

Moore not only recounts Dene stories and legends. Pearls of wisdom abound. He describes many examples of ingenious problem solving: how the community didn’t wait for the arrival of bulldozers and dynamite to clear away enormous boulders from a planned village air strip; the way to portage heavily laden canoes or dog sleds to where rivers could be safely navigated; how to survive travelling over broken ice; why you shouldn’t burn snow.

Burnt Snow is Moore’s personal journey as he lived, worked, traveled and hunted side-by-side with his Dene friends and adopted family. The fifty-one short stories/“chapters” also offer ethnographic details of Dene life during centuries of being hunter-gathers and then as they transitioned to a more sedentary existence under Canada’s colonial rule. This makes Moore’s narrative as valuable to anthropologists as it does to everyone curious about a fruitful encounter between two cultures. Burnt Snow: My years living & working with the Dene of the Northwest Territories is difficult to put down. Readers will crave even more tales after the last page is turned.

|

| This dog blanket was handmade in Gameti by Bella Bekale, mother of Kieran Moore’s Dene friend, John Bekale. With silk embroidery, dog blankets were often decked out with bells on the top. The lead dog’s leather collar often had a stiff wire sticking up from the top with a beautiful woolen pompon on the end. This opulent display of a woman’s handiwork would be exhibited on special occasions such as when trappers returned to the Hudson Bay posts to trade furs or when entire families would arrive in town for Christmas celebrations. The entourage of silk-blanketed dogs teams coming in the distance with their bells ringing and pompons swaying was an amazing site to behold! |

***

Here is a ten minute video of Kieran Moore offering a Snow Walkers Rendezvous outdoor program on how to assemble a traditional cariole dog sled. In the background you will see a team of Mahoosuc Guide Service’s aboriginal Gwich’in Dogs whose bloodlines go decades back to various parts of the Yukon Territories, where they were originally bred by native people. For the benefit of their many clients, Mahoosuc refers to their dogs as “Yukon Huskies”.