Table of Contents

*

Fan Mail

*

Featured Inuit Dog Owner: Ken MacRury, Part 2

*

Page from the Behaviour Notebook: Death and Transfiguration

*

Lost Heritage

*

Antarctic Vignettes

*

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part 4

*

News Briefs:

ISDI letter to the Editor of Mushing Magazine

Inuit Dog Thesis International Sales

Update: Traveling Dog Exhibit

*

Product Review: The Original Zipper Rescue Kit®

*

Janice Howls: PETAphiles

*

IMHO: Means, Motive and Opportunity

*

Index to The Fan Hitch, Volume 5

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

John Killingbeck drives the last team of huskies across the Antarctic. Killingbeck photo

A Lost Heritage

by John Killingbeck

There was a strange, slightly melancholy, feeling as John and I flew over the vast landscapes of the Antarctic. In the centre of the 'Twin Otter's' fuselage was a 12 ft Nansen sled and along the sides were our companions for the next two months, the husky dogs. Peering over the sledge were the friendly faces of the siblings, Roy and Pris, the gnarled old face of Max, the reserved and sad eyes of Pujok, the sharp inquisitive Morgan and the neurotic Urza. These dogs, called the Huns, and another team called the Admirals were about to set out on the last sledge journey on this continent.

In 1945 huskies were brought down to the Antarctic from Labrador to support the work of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (later known as the British Antarctic Survey). In these early days small bases were set up by ship on the Antarctic coast and the only way to travel inland was to use dog sleds. At one time over 200 dogs were being used and challenging journeys, lasting months, were made over mountains, sea ice and ice shelves.

The working life of these husky dogs came to an end in 1975, by which time aircraft, tractors and skidoos had taken their place. Some teams were left and played an important part in the life and morale of the bases, especially during the isolated winter months. The dogs provide the link with the Inuit people, with whom our knowledge of polar travel originated, the link with Scott, Shackleton and the dogs of Amundsen's Pole journey in 1911, and the link with the British Grahamland Expedition which had first explored these areas of the Antarctic Peninsula in the 1930s.

Under the 1991 Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty, the dogs had to leave the continent by April 1, 1994, as they were deemed by the international community to be non-indigenous species. The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) had only two teams left. As they represented an important genetic stock, it was decided to return them to their ancestral home in Labrador and to give them to the Inuit community.

Our journey was a final farewell to these dogs and a 'thank you' to generations of loyal, friendly animals. My travelling companion, mountaineer and polar traveller John Sweeny, and I intended to use the dogs in the traditional way, for supporting scientific work. We were not trying to complete a long, epic journey.

The bond between the working animal and man is a very special one. In the Antarctic their life depends on you and your life on them. The wolf connection is important. We foster the pack instinct and accept and build on the natural development of the King dog (the 'alpha male' or 'top dog' or 'boss dog' in the pack's hierarchy) within the team. One can't forget the wolf when one hears that haunting, yet beautiful, howl of the dogs on a cold moonlit night, echoing between the mountains across the snow and ice.

Our destination was Alexander Island, comparable in size to Denmark. Spectacular mountains rise to over 6,000 feet. To the east are the steep escarpments of the Douglas Range and to the west the Bach and Wilkins Ice Shelves fronting the Bellingshausen Sea. We were involved in a survey programme to fix the position of some of these peaks for future satellite-based mapping. We were also working on a glaciological project to drill ice cores every 10 km to establish a data bank of temperatures for the monitoring of climatic change.

Travelling is basic and simple. There is a compass on the sledge handlebars and a bicycle wheel with mileometer behind. As the dogs only travel at three to four mph, navigation by dead reckoning is used. The dogs love to pull and it is not difficult to drive a team. Words of command are short and simple: -drawn-out 'Ah now. . . down dogs.' An intelligent dog is selected and trained for the lead role. King dogs usually stay at the rear, as they are normally heavier and stronger than the others, but not necessarily more intelligent (often the reverse). The lead dog is often a bitch, since the leader does not do much of the actual pulling.

The Huns were always excited when we emerged from the tent with their lampwick harnesses at the beginning of the day. Starts are frantic and one hangs on the handlebars trying to keep the sledge-load upright. It is exhilarating and the adrenalin flows. For the first few miles the dogs defecate and urinate on the run. As soon as the teams are settled we ski alongside the sledge with a safety waist loop over the handlebars. Crevasses are our major concern. Dog harnesses are hand-tailored to fit snugly, so if a dog falls down a crevasse it is held on its trace, dangling above the abyss, and can be recovered. To have your team of dogs 150 feet in front is very definitely a safety factor.

We travelled every day except for two lie-ups in raging blizzards. Temperatures rose as high as 8 °C (40°F) but by 'night' were down to -15°C (9°F). At this time we travelled early, before the surfaces melted, and rested the dogs in the midday period. Winds are always the controlling factor: -5°C (23°F) with 30 mph winds is cold, and we suffered at the beginning with split lips and fingers and burnt noses and cheeks. Eating Marmite biscuits was a torture. The sunburn is exacerbated by the hole in the ozone layer, and seemed far worse than 30 years ago.

The Nansen sledges are works of art and have changed little over the last 50 years. They are made of ash with oak or beech laminated bridges. The runners are shod with 6 mm (1/4") polyethylene and there is a bamboo 'cowcatcher' at the front. Treated hide thonging and flax lashings provide flexibility over the bumpy ice. A piece of sprung wood with metal studs acts as the footbrake, and we use additional rope brakes under the runners on steep descents. The sledge bag on the handlebars at the rear holds spare gloves, thermos and bits and pieces. Food and gear are kept in boxes which fit on the sledge. The long polar tent, emergency gear plus the old-fashioned wooden-handled shovel lie lashed on top of the load.

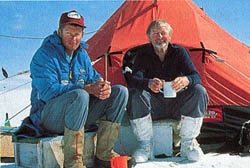

John Sweeney and John Killingbeck

outside their tent.

Killingbeck photo

We have a well rehearsed camping routine, quick and efficient. Dogs are spanned out and fed their bars of dehydrated Nutrican, the tent is erected, radio aerial and solar panels are fixed, snow blocks cut for water and all items made safe against blizzards. Within 20 minutes of stopping, a meal can be ready, cooked on the paraffin primus stove. Dog harnesses and clothes are hung to dry in the apex of the tent and a check is made on the air vent. Carbon monoxide poisoning is probably our greatest hazard. What luxury it is at the end of the day to slip into our down sleeping bags. The only words spoken during this time will probably be friendly ones to the dogs.

This way of life is based on years of experience and tradition. It is very simple and basic, without heroics, and it works. We live with our environment and try not to fight it; the Antarctic is far too harsh. We all wonder and marvel how the dogs can live outside in the blizzards down to temperatures as low as -50°C (-60°F). They curl up with noses on their paws, their great bushy tails covering them completely. They never come inside unless they are ill. Their friendliness comes from having been constantly handled since birth. It is virtually unknown for anyone to be bitten by one of them. They pull their own weight, so with dogs weighing between 70 and 100 lb a full team will pull around 1,000 lb.

Max & Pujok: the huskies live

outside even in blizzards.

Killingbeck photo

Our final traverse took us past the Schubert Inlet, the Corelli Horn and through the Quinalt Pass to the Colbert Mountains. We camped on the Purcell snowfield, but our music was not Schubert, Corelli or Purcell but the sound of the wind, the avalanches and the crunch of the sledge runners over the hard snow. Very few humans had passed this way before and, although we were not discovering anything new, there was still a sense of awe and privilege to have lived and travelled by dog sledge in this area of Alexander Island. Two proud, fit teams returned to their home at Rothera on Adelaide Island.

Among base members taken out for local sledge trips just before we departed the continent was Luke Bullough (BSc - Biology 1990) who was involved in a fascinating underwater biological survey among the icebergs off Rothera.

As each dog was led up the steps of the Dash 7 aircraft for the flight to the Falkland Islands, we could see and feel the sadness around. The dog spans were empty, the harnesses and traces hung in the hut. There was no waving of hands, just silent tears as the huskies departed on February 22, 1994.

The dogs spent three weeks in the Falkland Islands, spanned out on the grass behind Port Stanley. Here they were inoculated and adapted to a very different world, full of new experiences: horses, cats, children and new smells. They were a great attraction.

They travelled well on the 18-hour flight to Britain on an RAF Tristar, spent one night in quarantine at Heathrow and then flew British Airways to Boston, USA. John Sweeny then sledged the younger dogs 500 miles on the ice of Hudson Bay to their new home, Inukjuak. The older dogs later joined them by air. We hope the breeding programme will be successful and that they will contribute to the cultural revival of the Inuit dog.

Footnote: Sadly, during the summer six of the dogs died of a canine virus, though they had all been inoculated in the Falklands. Seven young dogs are left and one of the bitches is in pup. We hope that they and their offspring will survive and multiply.

John Killingbeck (BA, Geography, 1960) worked in the Antarctic for two and a half years as Base Leader in the South Shetlands after leaving Bristol. He was invited by the BAS to undertake this last sledge journey as the representative of hundreds of past drivers.

This article was first published in Nonesuch, the University of Bristol Magazine, Spring1995.

The Huns and the Admirals pause on

their farewell

journey. Killingbeck photo

Geneviève Montcombroux comments: All the dogs subsequently died. However, the story is a little murky. The pups may have survived and been taken away. Or it may be than one of the young males fathered a litter with a local not-so-pure Inuit dog. Or it may be that several dogs survived and.….