In this Post

From the

Editor

Passage: William John ‘Qimmiliriji’ Carpenter

QIA, Canadian Government Settlement

Media review: Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants

Media review: One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk

Update: A Book is Born

Passage: William John ‘Qimmiliriji’ Carpenter

QIA, Canadian Government Settlement

Media review: Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants

Media review: One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk

Update: A Book is Born

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor's/Publisher's

Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch Website and

Publications of the Inuit Sled Dog– the

quarterly Journal (retired

in 2018) and PostScript – are dedicated to the aboriginal

landrace traditional Inuit Sled Dog as well as

related Inuit culture and traditions.

PostScript is

published intermittently as

material becomes available. Online access is

free at: https://thefanhitch.org.

PostScript welcomes your

letters, stories, comments and suggestions.

The editorial staff reserves the right to

edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Harry and Innuatuk, Craig Harbour, 1931

Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants:

The Biography of Harry Stallworthy, RCMP

reviewed by Jeffrey Dinsdale

This review is of yet another book about a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Harry Stallworthy, his service throughout, and his incredibly strong relationship with Canada’s North. I was surprised to learn that the first edition of Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants was released in 2004, fifteen years ago. Where have I been, why had I not discovered this book earlier? Thank you to a very kind and insightful friend for gifting this book to me.

I was particularly intrigued by this book’s title which prompted a bit of research. I learned that ‘serge’ (of French origin) is the name given to a type of strong, twilled fabric made from worsted wool (sometimes mixed with silk) that is often used in making military uniforms. The term ‘red serge’ refers to the distinctive scarlet jacket of the dress uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). As for the term ‘polar bear pants’, I had always wondered about photos of some dog mushers/hunters wearing very distinctive pants made of polar bear fur. The men in these photos have always seemed to be Inuit and they always seemed to be from Greenland. I now know that these men were Inughuit, Greenland Inuit. The appropriateness of this book title becomes increasingly obvious as the story of the life of Harry Stallworthy unfolds and two very separate aspects of his world become one.

I would direct interested readers to the succinct yet comprehensive information contained in William R. Morrison’s foreword to this book. He highlights the fact that while the life and accomplishments of Harry Stallworthy are not well known, all will agree, especially after reading this work, that Stallworthy is “one of the most accomplished northern explorers in Canadian history.” Perhaps even more importantly, Stallworthy, an Englishman, was deeply involved in the ongoing and increasingly poignant issue of establishing and maintaining Canadian sovereignty over its arctic territories.

The author, William Barr, is Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Saskatchewan and a research associate at the Arctic Institute of North America which is located in the University of Calgary. Barr had access to the significant life-long correspondence that existed between Harry Stallworthy and his brother Bill, a resident of Gloucestershire, England. This correspondence, along with Harry’s wife Hilda’s diaries as well as a substantial volume of Harry’s reports, photographs and documents all ended up at the Arctic Institute of North America. These materials, augmented by Harry Stallworthy’s RCMP service file and medical file, provided the bulk of the personal information that is the basis for this work although other members of the extended family shared relevant correspondence and photos as well as family history. Additional information came from the family of Paddy Hamilton, an RCMP Constable who served with Harry Stallworthy at both the Bache Peninsula and Craig Harbour RCMP posts on Ellesmere Island. Harry was also deeply involved with a number of high profile and well documented arctic issues and developments.

Throughout this review I have quoted from this book. I should also note that this book includes a wide selection of photographs and other visual images that significantly complement the narrative. There are also excellent bibliography, notes and index sections to this book, no doubt reflecting the author’s experience as a researcher.

This book is a biography of the life of Henry (Harry) Webb Stallworthy, born in Gloucestershire, England on January 20, 1895 and died on Christmas day, 1976 in Comox, British Columbia at the age of 81 years. It “is not a political or administrative history…rather it documents the life of a young man who like so many others of his era and background (including my own grandfather), came to Canada just before World War I (and) found a new and adventurous life.” In the case of Harry Stallworthy, this life was largely spent throughout the northern/arctic regions of Canada and so this book is a valuable documentation of the history of a region “that was only then beginning to be incorporated into the Dominion” (of Canada). Perhaps inadvertently but certainly fortuitously, in the process this book offers up an unabridged, unique and truly comprehensive look at the historic working lives of the Inuit Dog and those who drove them.

For those readers who have, or actually do mush sled dogs, this man’s life story could be viewed as a dog musher’s dream come true. In the course of his travels by dog team he visited and opened cairns left by Robert Peary, Donald Baxter MacMillan and other arctic explorers; he travelled with the very Inuit who actually supported both Cook and Peary in their quests to reach the North Pole; he ran dogs and guarded gold shipments over the trail to the Klondike; he followed the route of the Lost Patrol by dog team along with Sergeant Dempster, the man who had discovered the fate of Fitzgerald and the rest of that ill-fated patrol; he met arctic explorer Peter Freuchen, who had travelled extensively with Knud Rasmussen; he was part of several lengthy long distance patrols, travelling thousands of kilometres by dog team in the process.

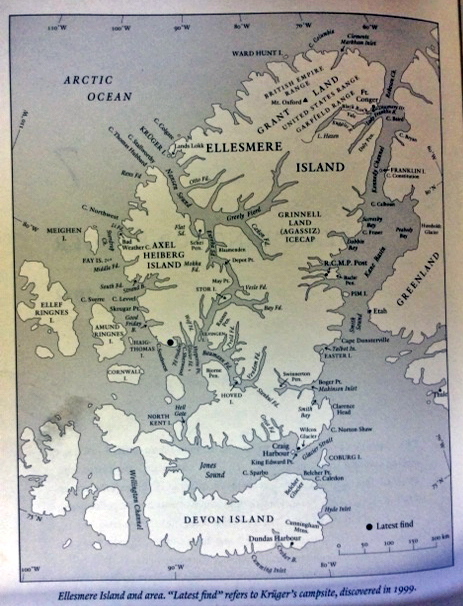

Ellesmere Island and the proximity of Bache Peninsula to Greenland

Mrs. Marilyn Croot

Harry Stallworthy… Life Chronology in North America

• November 1913: At age 28 he emigrated to Canada. His brothers were already living in Canada. He worked in Alberta doing farm labour and for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

• Outbreak of WWI.: A keen horseman, Harry saw that Royal North-West Mounted Police were looking for 500 recruits to form a cavalry detachment that would head to France as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

• September 25, 1914: He joined Royal North-West Mounted Police. The Expeditionary Force did not materialize.

• 1915: He posted to the Yukon at Dawson City, Whitehorse, Pelly Crossing and Selkirk.

• Spring of 1918: The RCMP did form an Expeditionary Force and Harry did go to France to fight.

• End of WW I: He returned to Vancouver, British Columbia and then back to the Yukon at Carmacks and Pelly Crossing where he patrolled the winter stage route that ran from Whitehorse to Dawson City (part of present-day Yukon Quest race trail) by dog team. He started gaining experience with sled dogs, ran five to eight dog teams using single file tandem hitch and wooden toboggans, enduring a very gruelling 388 mile trip to Ross River and return, half of which was by dog team.

• November 1919: The RNWMP became Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Harry stationed back to Dawson City.

• 1921: As a member of sled dog patrol under leadership of Staff Sergeant W.J. Dempster (of Lost Patrol fame), he traveled one thousand miles from Dawson to Fort McPherson and return, the last police patrol made on this route.

• 1921: He resigned from the force, took an extended prospecting trip in Yukon by dog team, canoe, on foot, thus experiencing wilderness living.

• May 1923: He re-engaged in the RCMP and posted to Chesterfield Inlet. He travelled on the famous HBC vessel Nascopie and met Peter Freuchen. Chesterfield Inlet is a hamlet located on the western shore of Hudson Bay at the mouth of Chesterfield Inlet in the Kivalliq region of present-day Nunavut. This marked the beginning of Hallworthy’s close relationship with Inuit. Naujaa became a very close friend and mentor. He was introduced to Inuit Dogs, learned how to run dogs Inuit style, and the Inuit way of life, completing several long patrols by dog team.

• 1925: At the end of term in Chesterfield Inlet he was posted to Edmonton, Alberta where he dealt with serious personal health issues. Following extended treatment, he posted to Jasper, Alberta where he met his future wife, school teacher Hilda Austin. In a 1927 letter to his brother Bill and in true RCMP reporting fashion Harry describes Hilda as “a very fine girl, 26, Canadian, pretty, slim, blond, blue eyes, good teeth.”

• 1928-1930: He posted to Stony Rapids where he established and essentially constructed a new detachment in this developing community located at the eastern end of Lake Athabasca. This was a period of development along the north and northeast shoreline of Lake Athabasca with the eventual establishment of mining communities including Goldfields, Uranium City and Stony Rapids (which is actually in the province of Saskatchewan but just south of the Northwest Territories – NWT – border). The established First Nations community in this region was Fond du Lac, home of the Chipewyan or ‘caribou eaters’ First Nation. There was considerable ‘traffic’ back and forth between Stony Rapids and Fond Du Lac. In retrospect, the 1930s was the commercial high point of the fur trade economy and several fur traders and trading posts were spread throughout this area. The major centre on Lake Athabasca was Fort Chipewyan which had been established in the 1790s by the Northwest Company. Enroute to Stony Rapids Harry travelled by rail to Waterways (Fort McMurray), down the Athabasca River to Fort Chipewyan by RCMP schooner to Fond du Lac and eventually to Stony Rapids. Everything needed to establish a new RCMP post in a new community was also being shipped at this same time and Harry picked up sled dogs and dog mushing equipment (toboggan and tandem collar harnesses) at the various stops enroute. There is a good chance that these dogs would have been Mackenzie River Huskies as Lake Athabasca is part of the Mackenzie River watershed. One of his first tasks once at Stony Rapids was to establish a fishery for dog food. The area beyond Stony Rapids was vast and ‘empty’ and Harry gained significant experience travelling by dog team. On one epic trip he estimated that he had covered 984 miles in thirty-three days of travelling. As he travelled northeast from Stony Rapids, actually entering the Keewatin area of the eastern arctic, “they encountered fresh Inuit sled tracks heading south along a river.” This would have been a significant moment in dog mushing history as the tracks of Harry’s toboggan pulled by five or six Mackenzie Huskies harnessed in single file crossed those of the Inuit qamutiq pulled by a team of Inuit Dogs running in the fan hitch. If he had kept travelling northeastward, he would have ended up at Chesterfield Inlet, NWT. This period of time was also his first experience with aircraft and he had one memorable flight over this vast area with legendary northern bush pilot icon C.H. (Punch) Dickens.

• 1930, Harry posted to be in charge of the remote detachment of Bache Peninsula at almost 80 degrees north latitude on the eastern coast of Ellesmere Island. This was the type of posting that Harry had been hoping for. The inhabitants of this post (Harry, his fellow officers and a few Inuit assistants) were the sole residents of Ellesmere Island. The big reason for the establishment of this remote post was Canadian concerns to clearly establish sovereignty over Ellesmere and other arctic islands. The more northerly site of Bache Peninsula was chosen as it was closer to the areas where Inughuit crossed Smith Sound to hunt muskoxen. In fact, at this period, the Canadian government was depending on the RCMP to act as an instrument for the establishment of Canadian sovereignty throughout the whole of the arctic. As an aside, this was also one of the main reasons for the establishment of the RCMP floating detachment, a sturdy little ship known as the St. Roch which operated primarily in the western and central arctic, but which also was the first vessel to complete both a west-east and an east-west journey through the Northwest Passage.

• “Hans Kruger, a German geologist and his party had passed through Bache Peninsula in March 1930, heading for Axel Heiberg Island and points beyond.” It was anticipated that Kruger and his party would return to Bache Peninsula before the summer of 1931. “When there was still no sign of him by the end of the year, it became evident that Kruger and his party had gone missing.” Harry (indeed the RCMP) and several Inughuit became involved in a lengthy, far ranging yet unsuccessful search for Kruger or at the very least for some indication of his travels and of his fate. This search involved the mustering of a significant amount of resources…men, dogs, supplies and equipment. The RCMP’s involvement was ultimately dictated by the desire to demonstrate Canadian sovereignty over this vast area. As recently as 2004 evidence of Kruger’s expedition was still surfacing, but without any confirmation of what exactly may have happened to the expedition members.

• 1933: The Bache Peninsula Post closed down and detachment moved south down the eastern coast of Ellesmere Island to Craig Harbour with Harry in charge. Bache Peninsula had proven to be somewhat inaccessible when it came to reliable resupply of this post. The Craig Harbour Post had actually been established in 1922 and throughout its lifetime saw intermittent use. It should be noted that there was also one additional arctic RCMP Post at Dundas Harbour on Devon Island. This post had been established in 1924 and saw use as both a police post and a Hudson’s Bay Company Trading Post. In 1934 approximately fifty Inuit from Cape Dorset, NWT were relocated to Dundas Harbour to establish an actual community, but all returned to the mainland thirteen years later. Dundas Harbour was populated by the RCMP again in the late 1940s to maintain a patrol presence, but it was closed again in 1951 due to ice difficulties, and this post was relocated to Craig Harbour.

• November 1933: Harry and Hilda (Remember her, the school teacher from Jasper from 1927, the girl with the good teeth?) were married in Ottawa, Ontario. They honeymooned in England where Hilda met Harry’s family. While in England Harry met with Edward Shackleton, son of the antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton regarding the mounting of the ‘Oxford University Ellesmere Land Expedition’. The desire was that Harry would be part of this expedition and would lend his knowledge and expertise regarding the arctic and arctic travel. “The main aim of the expedition was to explore and map Grant Land, the area of northern Ellesmere Island that lay between Lake Hazen and the Arctic Ocean and to conduct geological and biological research in that area.”

• February 1934: Posted to the RCMP Barracks at Rockliffe, just outside of Ottawa, Harry wrote an article regarding his experiences in the Yukon and at Chesterfield Inlet and Bache Peninsula and this was published in the October 1934 issue of the RCMP Quarterly.

• July 17, 1934: The Oxford University Ellesmere Land (Shackleton) Expedition leaves from St. Katharine’s Dock, London, aboard the Norwegian sealer Signalhorn with the support of the Canadian government and the RCMP. Harry spent some time in Etah (Greenland). He then travelled throughout Ellesmere Island as part of the Shackleton expedition. During this period, Hilda remained in England with Harry’s mother. The main objective of the expedition was to explore Grant Land from a base at Fort Conger or, if necessary, Bache Peninsula. However, the expedition was forced to winter 400 miles south due to pack ice. Despite this fact, they still hoped to make a brief visit to Grant Land, although there would be no time for scientific work.

• 1936: At the conclusion of the Shackleton expedition, Harry began his career as a ‘southern Mountie’. He had various postings with varied duties, beginning with a little bit of re-orientation/refresher training in Regina, Saskatchewan regarding the day-to-day duties of a regular RCMP member. He was posted to Fredericton, New Brunswick but stationed at Gaspé, Quebec with responsibilities for smuggling prevention, now at the rank of a full Sergeant. This was after all, the prohibition era.

• 1939: Harry was posted in charge of the detachment in Fort Smith which meant that he was in charge of a sub-division with eleven detachments under his control. This was truly the most southerly of all northern deployments. Fort Smith is located in the NWT on the Slave River, right on Alberta’s northern border.

• 1942: He left Fort Smith, posted to Thorold, Ontario, then Toronto.

• 1944: He was assigned to the security forces stationed in Quebec City on the occasion of the second meeting between President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, hosted by Prime Minister Mackenzie King.

• 1945: Harry retired from the RCMP and established the vacation retreat Timberlane on Vancouver Island

Inughuit

Inughuit were first contacted by Europeans in 1818 when explorer John Ross led an expedition into their territory. Ross dubbed them ‘Arctic Highlanders’. They have also been referred to as ‘Polar Eskimos’. They are believed to have lived in total isolation, to the point of being unaware of other humans. In the 1860s, an Inuit shaman, Qitdlarssuaq, led a group of approximately fifty followers from Baffin Island, eventually connecting with Inughuit in Greenland. It was through this contact that Inughuit regained much of their lost traditional knowledge about hunting and survival on the land. Inuit from Baffin Island intermarried with Inughuit, forming strong connections that are celebrated to the present day. In 1908 and 1909 Inughuit were instrumental in assisting Frederick Cook and Robert Peary on their claimed conquests of the North Pole. Their northernmost settlement was the village of Etah on the northwest coast of Greenland, a point that is very close (across Smith Sound) to Ellesmere Island. They then moved to Thule but in 1953 were displaced by the United States’ Thule Air Base at which time they relocated sixty-seven miles north to Qaanaaq.

Polar Bear Pants

“Harry’s first impressions of the Inughuit (particularly two assistants, Nukappiannguaq and his father Akkamalingwah) were very positive. Inughuit men were the only people among the Inuit who normally wore polar bear pants as a mark of their prowess as hunters…Dressed in these distinctive pants, these two men seemed vigorous, healthy and supremely self-confident. These adjectives applied particularly to Nukappiannguaq and his father Akkamalingwah who had worked for the RCMP at Bache Peninsula since 1925…(When Harry arrived at Bache Peninsula) he still had his caribou-skin parka (inner and outer) and pants from Chesterfield Inlet and he used these as his regular outerwear. But he was quite delighted when Enalunguaq took his measurements and shortly afterwards presented him with a pair of polar bear pants, as he felt that this was a sign that he had been elected an honorary member of the Inughuit.”

The Inuit Dog

The following is quoted directly from The Fan Hitch website and the Fan Hitch PostScript with significant thanks to Sue Hamilton, the person responsible for helping all of us develop an awareness and an understanding of the following significant classification.

“Although the Inuit Dog is often referred to as a ‘breed’, its proper identification is that of an aboriginal landrace:

• a class of domestic dogs that emerged as an ecotype within a specific ecological niche;

• largely the result of environmental adaptation, mostly under conditions of natural selection; influenced by human preferences and interference;

• fits the requirement of a specific human society living in a particular ecosystem.

Johan and Edith Gallant from their

Breed, Landrace and Purity: What do they mean?

The Inuit Dog is also a ‘primitive aboriginal dog.’ Profoundly different from ‘cultured’ breeds, they are still domestic but:

• have evolved by natural selection under conditions of free life and close interactions with people;

• are a unique piece of nature, time bound and place bound, most similar to zoological subspecies;

• are historically associated with ethnic groups and cultures;

• are the oldest and the only natural…dogs in existence.”

It should also be noted that “The term ‘primitive’ is sometimes disputed as incorrect and belittling of aboriginal dogs. The word ‘primitive’, in dog context, means natural, functionally justified and undistorted in appearance, behavior and health.”

Vladimir Beregovoy, PhD. from his

Evolutionary Changes in Domesticated Dogs:

The Broken Covenant of the Wild, Parts 1 and 2

Information about the sled dogs used by Stallworthy, the RCMP and Inughuit throughout the High Arctic is presented by this book’s author in a matter-of-fact, objective and impersonal manner. It should be remembered that the author is repeating information that he has researched from reports and letters. No attempt is made to present any of the dogs as individuals; there are no references made to any unique appearances, personalities or individual working abilities, and at no point is there any reference to any personal relationship between the dog drivers and their dogs. This reviewer believes that the documentation regarding the Inuit Dogs in this book lends further credence to the Gallant’s and Beregovoy’s classification of these dogs as a landrace.

All of the ‘sleds’ in use were in fact traditional qamutiit. It is clear from the text that these were the one and only type of ‘sled’ that could stand up to the incredibly rough treatment that was dictated by the brutal conditions. I note, however, that there are references to the fact that the runners of these qamutiit were shod with steel as there are no references to the traditional Inuit method of coating runners with frozen mud and water or urine. It is interesting to note that virtually all of the dog mushing equipment used was very traditional Inuit equipment. The harnesses, lines, dog boots were made of hide, probably seal skin for the harnesses and walrus hide for the traces and whips, with bone or ivory toggles. Caribou and bear hides were used for clothing, shelter and warmth. Igloos were usually the shelter of choice when on the trail, kayaks were used for hunting when the ice was not an issue. All of this very traditional equipment was ‘meshed’ however with kerosene fired burners and cloth tents. Radios were used as were motor powered launches or boats.

Once in the High Arctic/Ellesmere Island, there is no question that all of the dogs used were Inuit Dogs and it would probably be safe to state that these dogs were all sourced from Inughuit of Greenland. As the reviewer, I have chosen to select quotes from throughout the book’s text that convey an image of the conditions under which these dogs were living and working. My comments are not to be seen as a narrative, and no attempt has been made by me to list the quotes in any kind of chronological order. It is hoped that this approach might demonstrate just how this aboriginal landrace evolved in response to meeting the conditions, challenges and realities presented by the environment in which these dogs lived. All references are to experiences with these dogs in either Greenland or on Ellesmere Island.

• “Extremely important to procure dog food (bear, narwhal, walrus, fish or seal) before freeze-up since the detachment’s dog teams were crucial for transport. Harry found that imported dog pemmican was a poor substitute. When (Harry) took over, the detachment had 21 dogs (a total of two dog teams), while Nukappiannguaq and Akkamalingwah probably each had about 10 or a dozen dogs.”

• “Frozen meat (walrus, polar bear, seal, caribou) is chopped and pried out of a frozen pile and chopped up and fed to the dogs during the dark period…”

• “Initially the police dogs were not of very good quality, most of them being quite old...Harry made a conscientious effort to rectify this situation over the winter. He shot a total of eight old dogs and replaced them with eight younger dogs—six bought from visiting Greenland Inughuit and two from Nukappiannguaq or his father. He also improved the situation by breeding from the better bitches so that by the end of his first year (30 June 1931) he had 15 good pups from this source, plus a further six pups that came with one of the bitches he had bought.”

• [At Godhavn on Disko Island] “Harry had let it be known that he was looking for dogs and when he went ashore about 200 were presented for his inspection. Of these he chose the 50 that in his view ‘would compare favourably with some of the best average dogs in Northern Canada’…”

• [At Jakobshavn] “Harry selected and bought a further 20 dogs and a quantity of sealskin line. He also bought….4 ½ tonnes of dried fish for dog food…”

• “…Harry hired his old friends Nukappiannguaq and Inutak…along with their wives Enalunguaq and Natow, sledges, dog teams (25 dogs apiece), kayaks, hunting gear and household effects…”

• “Feeding, exercising and generally looking after the dogs took up much of each day. [The dogs] were provided with windbreaks made of boxes and snow…cutting up frozen walrus meat or fish provided the expedition members with some quite strenuous exercise...each dog received about 1½ kg. every other day.“

• “The [Shackleton] expedition members spent time learning to drive their own teams, with varying degrees of success….They were using a fan-hitch and so they all had to learn to deal with the task of unravelling the tangled knot…that resulted when the dogs jumped over each other’s traces….as they ran along.”

• “The detachment maintained five dog teams throughout the winter—an average total of 100 dogs, since the Inughuit drove teams of 14 – 19 dogs.”

• “...they carried the last of the outfit up the hill, then took up the five sledges and 59 dogs and loaded the sledges…once the loading was complete Harry and Moore [A.H. Moore was the biologist and photographer for the Shackleton expedition] set off….driving a team of 14 dogs and lifting the sledges over rocks in places. They descended to the shore ice…they saw that only a narrow icefoot clung precariously to the cliffs. They decided to wait for high tide since at low tide a slip would mean a fall of some 12 feet onto rocks. The icefoot was also less likely to collapse at high tide...”

• “Harry and his party made their final preparations. They filed the sledge runners, which had been scored by scraping across rocks and gravel...the total weight of their outfit approached 3,000 lbs.—the largest item being dog pemmican at some 1,500 lbs. The men’s own rations weighed 480 lbs., kerosene 240 lbs., robes, skins, spare clothes, camping equipment, cameras and film, scientific instruments, firearms, ammunition, hunting gear and other miscellaneous items came to

approximately 750 lbs. The total load on each of four of the sledges was 650 lbs...”

• “…they ran across the sledge tracks of two Inughuit heading north on a bear-hunting trip. They met the two men who were heading south from their bear-hunt north of the Humboldt Glacier. They had seen no bears, had been unable to get any seals for their dogs (who) were starving. They had already lost five out of 18 dogs and had just killed two more to feed to the others. The men’s faces were badly frostbitten. Harry and Moore gave them 1 lb. of pemmican for each of their dogs, and a good meal for themselves”

• “By now the dog food was almost exhausted and they were feeding what was left mostly to the bitches since the Inughuit were anxious that at least their breeding stock would survive. The objective now was to reach either the cache at Cape Southwest or country where game was available before all the dogs died Since leaving Cape Thomas Hubbard they had been travelling 18 – 20 hours per day and the dogs were very thin and towards the end of each day some dogs in each team had to be carried on the sledges.”

• “The dogs although being [fed] regularly on pemmican, were getting poorer through lack of fresh meat and subsequently becoming slower.”

• “The hunters killed two small bears at the cape and these were fed to the dogs.”

• “By morning the fog had cleared...travelling conditions were as bad as ever and the dogs were slowing visibly. By evening some of the younger dogs were riding on the sledges; and that night they fed the dogs the last of the pemmican. When they emerged from their snow house in the morning, the men found that several dogs had broken loose and had eaten some of their traces as well as Nukappiannguaq’s qulitaq [parka].”

• “I knew I would never again depend upon (pemmican) as a source of dog feed…True, so far it had kept the dogs alive, but that was all that could be said in its favour. It had given them diarrhoea, and at times, had caused them to vomit. Now they were thin and unable to pull. It might have been all right provided we had had quantities of seal or walrus fat to mix with it...here in the middle of the Arctic no man’s land, where the dogs had to be on the move every day pulling heavy loads, it was absolutely useless…the stark truth was that we had no dog feed of any kind, and the outlook was grim.”

• “They reached the cape at midnight, having killed only one small bear en route. The Inughuit had to stalk it on foot since the dogs no longer had the energy to pursue a bear and bring it to bay; during the crossing, five more dogs died of starvation. Fortunately, at Cape Southwest they found that Inuatuk and Seekeeunguaq had killed and cached enough bear meat before they started for home to give the remaining dogs a feed. Pushing on along the south coast of Axel Heiberg Island, it took the party 24 hours to cover the 50-odd miles to Glacier Fjord through deep snow. The men had to walk alongside the dogs to encourage them along the way. On spotting a herd of 18 muskoxen grazing on the west side of the fjord, Paddy reluctantly decided to shoot three of them to feed both dogs and men.” [Note: Since 1917 all arctic travellers were under strict orders from the RCMP (the Government of Canada) that under no circumstances were muskoxen to be killed. This reflects concerns about diminishing numbers of muskoxen throughout all of Canada’s North, it also reflects concerns that it was Inughuit hunters from Greenland that had historically been hunting these animals on Ellesmere Island (Canadian soil).]

Paddy Hamilton's team, Bache Peninsula, 1932

from the Arctic Institute of North

America’s Stallworthy Collection

• “At midnight on the 18th the three sledges headed for Hoved Island, but a southeasterly blizzard brought them to a halt and pinned them down for the whole of the 19th and 20th…when the storm abated on the evening of the 21st they started off again…Nukappiannguaq spotted a large bear approaching. He took the best of the dogs from the three teams and drove off in pursuit of the animal…he eventually caught up with the bear and shot him…by morning the snow was hard and the dogs were well fed and rested...they made good progress and the men were able to ride on the sledges again”.

• “Having killed two caribou during the day they had enough meat to tide them over and so when they reached the head of Makinson Inlet …they stayed there for two days to let the dogs rest and eat and also to repair sledges and harnesses while a northerly blizzard blew itself out.”

• “They killed a bear later in the day...the next day they crossed Talbot Inlet, which was bounded by a spectacular glacier front…Passing through the narrow strait behind Paine Island, they were halted by open water lapping at the cliffs…after retracing their steps for eight kilometres they found a route overland across a glacier. The descent from the glacier back down to the sea ice was precipitous; they had to unharness the dogs and line the sledges down individually. At this point a further three dogs that had still not recovered from their protracted period of starvation on the west coast died.”

• “Hamilton’s patrol had lasted 49 days during which time he...had covered approximately 1,510 km. Because of the paucity of game, they had lost 17 dogs from starvation.”

• “The next few days were spent in final preparations, which included building another komatik to replace Ittukusuk’s which was in very poor condition. Meanwhile the women were kept busy until the last minute, sewing bearskin pants, socks, mittens and other clothing.”

• “Since getting fresh meat was a primary concern at this point, they discarded one sledge and some equipment at Fort Conger and combined the dogs into two teams of 16 dogs each. Before leaving Fort Conger they fed the dogs a small amount of the canned meat from Hansen’s cache, along with some sealskin kamiks and harness, cut into small pieces...since this was the most northerly patrol undertaken by any member of the RCMP, Harry also left a brief note with a request that the finder forward it to RCMP Headquarters in Ottawa.”

• “Next morning an ujjuk (walrus) surfaced near camp; Inuatuk shot and killed it but it floated towards the ice edge with the strong current. Inuatuk fortunately managed to harpoon it before it disappeared under the ice…all the worries about dog food were now over since the meat and blubber totalled about 800 lbs. and they were able to feed the dogs to repletion.”

• “During the dark period from 18 October to 23 February, all five men and the teams were kept busy hauling dog feed back to the detachment from the various caches of walrus, narwhal and seal meat accumulated in the fall. Most of them were within 20 miles of the detachment, but the largest trip involved a round trip of about 70 miles. As usual the snow was loose and deep, making for heavy sledging and/or fairly light loads. Harry put a positive spin on all this activity: ‘The two police and three native teams were all kept in good condition at this work which was also a benefit to the members of the detachment in that there was an objective and good reason to get out and travel in the winter...meat hauling trips accounted for a total mileage of 7,000 miles over the winter.”

• “As was so often the case, the frequent easterly winds had blown the ice out, leaving a stretch of open water to the south of Foulke Fjord. As a result, they had to ascend the Brother John Glacier and cross the icecap...the glacier front was snow free and they had to chop steps in the ice.”

* * *

Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants: The Biography of Harry Stallworthy, RCMP by William Barr; ISBN 978-0-88864-433-6; is a 6” x 9”, 400 page paperback available from the publisher, University of Alberta Press, for CAD34.95, USD34.95, GBP24.99 and from online retailers.

A recommended complementary read to Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants is The Long Exile – A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic (Melanie McGrath), published by Alfred A. Knopf Division of Random House, 2007.

Other titles regarding RCMP presence in the Canadian North:

The Lost Patrol (Dick North)

The Mad Trapper of Rat River (Dick North)

Northern Service (Doug Byer)

Yukon Memories – A Mountie’s Story (Jack ‘Tich’ Watson and Gray Campbell)

Pursuit in The Wilderness (Charles Rivett-Carnac)

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Richard L. Neuberger)

Mountie in Mukluks – The Arctic Adventures of Bill White (Patrick White)

Dauntless St. Roch – The Mounties’ Arctic Schooner (James P. Delgado)

Arctic Assignment – The Story of The St. Roch, (F.S. Farrar)

And if facts aren’t enough there is always fiction, like Scarlet Riders – Pulp Fiction Tales of the Mounties (edited by Don Hutchison).

About the reviewer:

One of Jeff Dinsdale’s many passions are sled dog and polar history. Enjoy more of these accounts on his Mushing Past blog. The other is as one of the organizers of the annual Gold Rush Sled Dog Mail Run. Jeff and his family live in British Columbia where for a very long time he has raised and traveled with Inuit Dogs.

Ed. The Fan Hitch thanks both Jeff Dinsdale for seeking permission and the University of Alberta Press for granting the inclusion of extensive quotes for this book’s comprehensive review.