In this Post

From the

Editor

Historic Nansen Sledge Gifted

The Enduring Love of Those Huskies

Flush at Stonington in 1964

Film Review: Atautsikut – Leaving None Behind

The Qikiqtani Qimuksiqtiit Project

Web News: Greenland Travel Guide; Inuit Literature Website; Another failed social experiment

Defining the Inuit Dog: web pages refreshed

Historic Nansen Sledge Gifted

The Enduring Love of Those Huskies

Flush at Stonington in 1964

Film Review: Atautsikut – Leaving None Behind

The Qikiqtani Qimuksiqtiit Project

Web News: Greenland Travel Guide; Inuit Literature Website; Another failed social experiment

Defining the Inuit Dog: web pages refreshed

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor's/Publisher's

Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch Website and

Publications of the Inuit Sled Dog– the

quarterly Journal (retired

in 2018) and PostScript – are dedicated to the aboriginal

landrace traditional Inuit Sled Dog as well as

related Inuit culture and traditions.

PostScript is

published intermittently as

material becomes available. Online access is

free at: https://thefanhitch.org.

PostScript welcomes your

letters, stories, comments and suggestions.

The editorial staff reserves the right to

edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

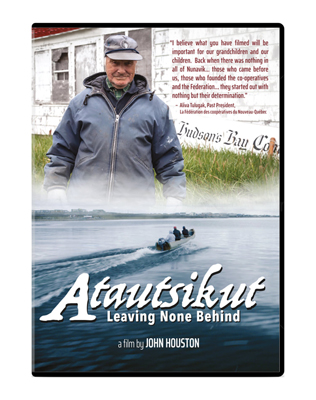

Atautsikut:

Leaving None Behind

a film by John Houston

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

a film by John Houston

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

Traditionally, before the arrival of outsiders, Inuit harvested animals from the land, sea and skies for their own needs, be it food, clothing, heating (seal oil for the qulliq) and virtually all their tools from bone needles and sinew for sewing; to hunting weapons; to hides for harnesses, footwear and summer housing; to qajaat and umiat for summer travel and qamutiit in the winter. Some material came from non-living sources – stones and rocks. Polar Inuit (Greenland) even fashioned implements from their Cape York iron meteorites until Robert Peary stole them (1894/1896) and sold them to New York City’s American Museum of Natural History.

Outsiders in the North had many motives for being there, among them was the recognition of a “goldmine” of fur bearing animals that would bring them enormous wealth sold to the European market. Initially starting out as “gifts” from first encounters, Inuit found some offerings alluring or useful. This was followed by Inuit trading for these items. Their “currency” was furs: principally white fox pelts. Strategic posts were established across the North and Inuit were encouraged to harvest as many pelts as possible. The mid-1600s marked the early beginnings of one of the best known of the fur trading businesses, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC or The Bay).

HBC outposts evolved into more than just trading furs. They became the place to buy goods of all kinds – a general store. Their profitability depended on how large a margin they could extract (and how they would do that) from Inuit and Cree who became increasingly dependent on and desiring of items they either previously fashioned from their hunting efforts, or hunting implements themselves, or things unrelated to those such as tobacco, flour, sugar, tea, coffee and cloth material. This system persisted. From their very beginning, with the HBC “the only game in town” calling the shots, it was the white man who set the rules of exchange and to his advantage.

From his childhood, Canadian John Houston has been immersed in the lives and culture of Eastern Arctic Inuit. His body of work is reflected in his skilled filmmaking revealing a deep-rooted understanding of and respect for northern culture. Atautsikut: Leaving None Behind is his frank examination of the evolution of the Inuit cooperative system, born literally out of hunger and the struggle for independence from the domineering Hudson’s Bay Company system of “doing business” with (or perhaps viewed as sticking it to) Inuit and Cree of Arctic Quebec (what is now Nunavik).

Inuit interviewed in this candid documentary acknowledge that life as nomadic hunters and trappers was often a struggle, but the freedom to make their own choices was theirs. This freedom began to erode first with the lure of offerings by outsiders: sweets, tobacco, etc. Powerful archival footage later shows scores of Inuit men and women toiling to move huge barrels and wooden crates from a ship to a Hudson’s Bay post building. Treated as second class citizens in their ancestral home, how could it possibly have come to be?

The cost of a rifle would be fox pelts piled has high as the rifle on end. But the HBC staff would compress that pile of pelts as much as possible to “up” the cost of the rifle. Zebedee Nungak told the story of his grandfather who was leaning over the counter to view some folding knives when the HBC employee, unprovoked, punched him hard in the side of his head. HBC kept ledgers indicating in their opinion which Inuit and Cree were worthy of loans. “Yet another example of abuse of power”, Houston later explained. “Inuit lived in fear of being marked down in that ledger, afraid they would be cut off from the loan of a couple of pounds of flour, sugar, lard, a few replacement leg-hold traps, a few bullets… because without that loan, they would effectively be cancelled as providers, becoming wards of the Inuit community. This was textbook colonialism, with qallunaat or white people holding all the cards.”

These exploitations and mistreatments were what inspired the cooperative movement. As Lucy Grey stated, “The co-ops were started because Inuit were piss, piss poor.” In the old days, if a hunter had poor luck finding game, he’d be helped by others in the group. But now when Inuit were hungry, starving, unless they had something to trade, HBC storehouses full of food remained locked.

Three qallunaat were featured in the documentary as being allies, helping Inuit to rise above their dire situation.

James A. Houston (1921-2005), the filmmaker’s father, arrived in Nunavik in 1948. An artist and a visionary, Houston saw the enormous potential of Inuit talent. He continued to encourage Inuit to develop their carving as well as print making and other artistry. He is considered instrumental in bringing awareness and fostering an important worldwide market for Inuit creativity.

“First Caribou”

John Houston, writer/director of Atautsikut: Leaving None Behind, reflects on this soapstone

carving given to his father by Conlucy Nayoumealook (1881-1966) in 1948. In the film, Sarollie

Weetaluktuk explained to John, “This small carving of a caribou actually saved Inuit lives after

Nayoumealook carved it as a gift for your father and your father in turn made it known worldwide.”

In the documentary there is a touching scene where this very carving is lovingly passed among

many of Nayoumealook’s descendants who speak in awe of its significance: “This was the first.”

“I never thought I’d hold this… never thought I’d see it.” Photo: Dennis Minty

Peter Murdoch (1929-2015) initially worked for the HBC, but he preferred to help people in need, encouraging indigenous people to become independent yet still cooperate among themselves. Inspiring Inuit to lift themselves out of poverty while still working for the HBC, Murdoch secured the permission of Inuit in the camps to set aside 5% of their earnings from every trade. Through their carvings and pelts, Inuit saved enough that they could buy tools and boats without a loan.

Father André Pierre Marie Steinmann, OMI (1912-1991) was a missionary who was described by Puvirniturmiut as never having converted one Inuk during the many years he ministered in their area. Able to speak Inuktitut, he was more concerned with peoples’ need to never be hungry, to have something to look forward to in life. With few natural resources in the Nunavik community of Puvirnituq, he worked to promote Inuit carvings, even reaching the ear of Canada’s Prime Minister. He organize a carvers’ society (along with Peter Murdoch). Fr. Steinmann opposed the use of the Inuktitut word for bosses applied to HBC employees, insisting that Inuit had the same brain and capabilities as qallunaat. He was credited with what was to become the motto of the cooperative system’s federation “Atautsikut: Leaving none behind.

Attributed to Sammy Kakkinerk of Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik

Courtesy of Ilagiisaq/FCNQ

Starting with nothing but raw determination, the first co-op was established in George River, now known as Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik in 1959. La Fédération des coopératives du Nouveau-Québec (FCNQ), established eight years later, represents the co-ops in the fourteen Nunavik communities. Early on, when the European popularity of fox garments dwindled, carvings took over as the major commodity. Added to this were other handicrafts such as limited edition prints, dolls, baskets and, adopted as the widely known symbol of Canadian trade, the ookpik (owl) made of fox, then of seal fur. Starting up, some co-ops were more successful than others. Remembering how Inuit were starving while the HBC coffers were full, the co-op system set aside 1% of its income to help those members in need.

Today, the FCNQ website describes itself as “…the largest non-government employer in the region…managed exclusively by Inuit and Cree staff, thereby ensuring that the knowledge and experience gained from operating their collective enterprises remains an asset of the community…” The Federation is well diversified: “Operating retail stores with a wide selection of merchandise at competitive prices, often paying back savings in cash and shares to members at the end of the year; banking, post offices, cable TV and internet services; management training, staff development and auditing service; marketing Inuit art across Canada and around the world; operating hotels, a travel agency and hunting and fishing camps, bulk storage and distribution of crucial oil & fuel supplies; construction projects in Nunavik for housing, schools, etc.”

Their success has not gone unnoticed elsewhere. FCNQ delegations have traveled to South America advising indigenous groups there to better organize and improve their struggling co-ops. Ilagiisaq/FCNQ is also the recipient of the Co-operatives and Mutuals Canada (CMC) Large Co-operative of the Year Award. This award honors Canadian organizations that have made a significant contribution to the co-operatives and mutuals sector in Canada and/or internationally.

Atautsikut: Leaving None Behind is the powerful story of the development of the cooperative system, from millennia of Inuit fortitude surviving by their own wits before outsiders arrived, then interrupted by entities such as the HBC, followed by a reawakening of their natural talents and ability to adapt, to learn new skills, to survive and to succeed in a dramatically changing socio-economic landscape. This is an astonishing transformation of a culture for whom money was once an abstract concept to one managing a half-billion dollar enterprise! At the FCNQ’s 50th anniversary celebration, Aliva Tulugak, sculptor, former FCNQ president and co-author (with Peter Murdoch) of A New Way of Sharing: A Personal History of the Cooperative Movement in Nunavik, proclaimed, “People who live in the land of the qallunaat find it astonishing. How can a people who never learned the French and English languages and have never been in a university progress? By moving forward together, leaving none behind!”

Great good friends:

John Houston and Aliva Tulugak

Photo courtesy of John Houston

Atautsikut: Leaving None Behind, 2019, is 60 minutes-long and includes versions in English, Inuktitut and French; with lots of personal stories told, archival stills and footage including some of Inuit Dog teams. Available from Houston Productions in Blu-ray or DVD for $30.00 CAD plus shipping; Also available as Video on Demand from Vimeo (rental).