In This Issue....

From the Editor: New Realities

In the News: Must-visit WebsitesBAS Vignette: Memories of a Non-Doggy Man

Sledge Dog Memorial Fund Update

Lost and Found: Recovering Dogs Gone Astray

Book Review: Hunters of the Polar North

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor's/Publisher's Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The

Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled

Dog, is published four times a year. It is

available at no cost online at:

https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

John Shepherd with the Mobster's sledge photo: Shepherd

Memories of a non–doggy man

or

Why I bought the painting of Changi

by John Shepherd, Devon, England, 16 Feb 2008

In the latter part of the 1950s my father was an officer in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and twice during this period he was posted to Singapore and the family went with him. In those days Singapore had three RAF stations: RAF Changi, RAF Seletar and RAF Tengah. We lived at Changi. As children living on a tropical island, for a total of three and a half years, we had a fantastic time. School was mornings only (but that did include Saturday mornings), but each afternoon was spent roaming the beaches or down at the swimming pool. When we left I was about twelve years old and already had many happy memories of Changi and Seletar.

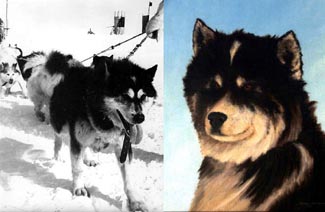

I believe it was an ex-Royal Air Force technician, who later became a FID at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) base at Halley Bay (aka Halley II), and who named the litter of six dogs born to Frosty and sired by Balasuaq after these RAF stations. The other three pups were named Luqa, Fedu and Sharjah, which were RAF stations in Malta, the Maldive Islands and the Persian Gulf respectively. The litter was born in 1966, but at that time little did anyone realize that two of the dogs, Changi and Seletar, were destined to become two of the best lead dogs ever born at Halley Bay.

I joined BAS in 1970 as a wireless operator mechanic and arrived at Halley Bay in the Antarctic summer of 1970/1971. Halley Bay was and still is a scientific station, famous for its 1985 discovery of the ozone hole. In the period up to the summer of 1969/1970 it was also a major field base concentrating on the geology of various nunatak ranges some 200 to 400 miles (322 to 644 km) from the base. This work was completed in the 1969/1970 summer and when my intake arrived at Halley Bay late in 1970, we found a fully operational field base with about fifty huskies, and it has to be said a few vehicles, but essentially there was no field program. This was quickly remedied because the local area work, glaciology and mapping, had been neglected in favour of the work in the mountains. It thus became a great opportunity, for all those who normally would be tied to base by their jobs, to get out on field trips. And because there were two wireless operators at Halley Bay in 1971, we were able to cover for each other when one was out in the field.

My first field trip was with base electrician Mike Taylor and an eleven-dog team lead by Frosty (Changi's mother) on a standard, center trace with five pairs plus the leader. The scientific reason for the trip was to go out onto the sea ice and measure the seawater temperature at intervals down to a depth of 109 yards (100 m). I can remember on one occasion we had left the team securely staked out and were some distance away, lowering our measuring equipment into the water, when we saw a lone Emperor penguin walking straight toward the team. In an effort to save the over-curious bird we started running back to the sledge. Frosty, however, was a wily old girl. She had deliberately backed off so her trace was slack when the penguin unfortunately got within her range. Before we returned to the sledge, Frosty had grabbed the bird and pulled it back into the team. From the resulting eruption of noise we expected the worst, but suddenly the penguin shot out from the pack, moved about ten feet from the team, stood up and stared at them. Amazingly the bird appeared to be totally unharmed. I suspect a couple of the dogs had got a firm clout on the nose from a powerful flipper and got discouraged somewhat. The score was definitely Dogs 0 - Penguin 1.

| Seletar photo: Shepherd |

Mike Skidmore's Changi portrait, won by John Shepherd |

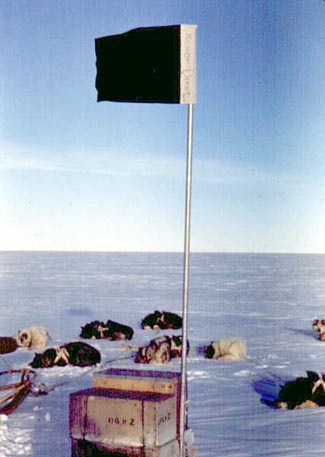

The Mobsters resting at the Kilroy Depot

photo: Shepherd

The following day we ran into a bit of trouble. We had been mapping the coastline all morning, about 100 yards (91 m) upslope from the ice cliffs. We had just turned a corner when one of the back pair of dogs dropped his hind legs into a crevasse. He struggled out and luckily did not make a fuss. Obviously we could not stop the sledge at that point, so we carried on about ten yards and then Muff went back to check. The hole was seven to eight feet (2-2.5 m) across and at ninety degrees to our course. The problem was we could not go down-slope because of the ice cliffs and there was another crevasse upslope running parallel to our course. So armed with the bog chisel (crevasse detection device), Muff went off to find a safe route through the crevasses. There are some days when you are just glad you were not a G/A. All I had to do was enjoy the view and stay with the dogs who, if you stopped for more than a few minutes, always curled up and went to sleep. It was one of those rare days when the sun was shining and air was so clear you could see forever. I could see the hundred foot (30 m) ice cliffs of the Riiser-Larsen glacier stretching for miles in a gentle curve, all the way to the eastern horizon. The sky was pale blue with a few fluffy, white clouds that contrasted sharply with the dark-blue sea and the pristine, immaculate tabular icebergs drifting slowly west down the coast. I could also see a very tiny dot in the distance waving at me. It was time to go.

"Muff" Warden carefully checks for crevasses

photo: Shepherd

I walked down the main trace to Seletar the leader and took out the front picket. When I turned around I had all eleven of the dogs staring at me, giving me their 100% attention. The dogs were not only ready but practically quivering with excitement. One wrong word or a sudden movement would have triggered them and I would have lost the sledge. That would have been the ultimate embarrassment. I walked slowly to the back of the sledge. When you take out the back picket on the sledge on your own, I was taught never to stand on the snow and pull it out. That is just another good way to lose a sledge. You stand on the sledge and kick the picket out. The first kick did not free it so I was about to try again when the dogs lurched forward in their harnesses and dragged it out. We were off! I immediately shouted the "GO" command just to let the dogs know they were acting on a command and not on their own initiative. I don't really think I convinced them. The sheer exhilaration of that ride along that long slope and down onto Riiser-Larsen Glacier is probably one of the best memories I have of those days. Eleven dogs running flat out pulling a light sledge. It doesn't get better than that! I remember shouting encouragement to them, but I don't think they needed it as they were doing what they loved to do.

There were days on base when you were snowed under with work and fed up and the only cure was to climb out (Halley II was buried thirty odd feet (9 m) under the snow surface) and go to see the dogs. If you went out at night during an aurora display, all the base surface lights would be turned off, because the all-sky camera would be running and the sky would be full of pulsating green lights. Ground drift would be snaking lazily across the surface. With luck the dogs would be singing for you. There is something primeval about a large number of huskies howling. It was impossible to record and difficult to photograph, but it is an enduring memory.

There were many happy memories but some sad ones too. I remember doing the base radio sked in early February 1972, with the sledge parties returning from a trip through the hinge zone, when they reported in the loss of their sledge and all nine members of the Hobbits team, including Changi who was their leader. The rear of their sledge had broken through a crevasse lid running parallel to their course. So narrow was the crevasse that the two men travelling with the sledge ended up on opposite sides of the hole. The sledge and team were gone in seconds. The subsequent salvage operation measured the depth of the crevasse at over 180 feet (55 m), with no intermediate bridges to break their fall. They must have died instantly.

I am proud to have been at Halley, especially when the dogs were there, and feel very privileged to have been able to go out with them. It is very unlikely I will ever do anything like it again, so the painting of Changi represents to me all the dogs at Halley and all the memories of those days. It is not my intention, however, to keep the painting. Halley VI, the latest British base to be built on the Brunt Ice Shelf, is due for completion next year and I am hoping they will give the painting a permanent home. The huskies are part of my history and they are also part of the history of all the FIDS who go to Halley. It will be good to remind future generations that we were not always alone down there.

The Mobsters team in modified fan trace

photo: Shepherd