From the Editor

Fan Mail

In the News

Evolutionary Changes in Domesticated Dogs:

The Broken Covenant of the Wild, Part 4

An Examination of Traditional Knowledge:

The Case of the Inuit Sled Dog, Part 1

Greenland Dogs of the Eiger Glacier

Boss Dogs and Lead Dogs

Tip: Pack Your Parka

IMHO: Two "New" Dogs

Navigating

This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor's/Publisher's Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal of

the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four times

a year. It is available at no cost online

at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

This article

is available for download in .pdf format.

Click here

to begin download

West Siberian Laika male with his owner, Carol Stanton, in USA.

Photo: Vladimir Beregovoy

Evolutionary Changes in Domesticated Dogs:

The Broken Covenant of the Wild

Part 4: Preservation

by Vladimir Beregovoy

Buchanan, Virginia, USA

West Siberian Laika male with his owner, Carol Stanton, in USA.

Photo: Vladimir Beregovoy

Evolutionary Changes in Domesticated Dogs:

The Broken Covenant of the Wild

Part 4: Preservation

by Vladimir Beregovoy

Buchanan, Virginia, USA

Preservation of hunting, working and primitive aboriginal breeds

After domestication of the wolf, evolutionary changes in the dog went through three successive and overlapping time periods: 1) primitive aboriginal dogs, 2) cultured breeds and 3) show-pet dogs. Now, all hunting and working breeds are threatened by genetic pollution and replacement with genetically crippled show-pet dogs.

Conservation of aboriginal breeds is possible only if they are preserved as parts of their natural habitat, including their work and way of life. Unfortunately, people abandon a traditional way of life along with the dogs of their ancestors even in parts of the world remote from industrial centers. In the long run, the future of the majority of primitive aboriginal dogs seems rather bleak. However, there are a few hopeful projects subsidized by governments and charitable funds aimed at preservation of aboriginal dogs within their environment. In Bulgaria, Atila and Sider Sedefchevs are working on the preservation of the whole natural complex of their country, including the Karakachan dog, the Karakachan sheep and the Karakachan horse. The project covers predators as well, such as bears and wolves, without which the work of the Karakachan dog would not be needed. In Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan livestock guarding dogs became recognized as national breeds and they are still used for protection of sheep in open mountain pastures. Sheep guarding dogs were imported to the United States of America from several countries of their origin. Therefore, they represent a mixed stock. Nevertheless, they originated only out of aboriginal dogs of similar functional purpose and now form a healthy population. Interesting work on preservation and restoration of national livestock protecting dogs is being done in Portugal and sled dogs and reindeer herding dogs in Russia.

The same is going on with aboriginal sight hounds. However, some of them are represented by both working and show lines and genetic exchange between the two may ruin the working lines.

Attempts to rescue aboriginal dogs by breeding them in an urban environment with a plan to return them back in their home country when economic situation improves may help, but only as a temporary measure. There are several pedigreed breeds derived out of aboriginal dogs and adopted by major kennel clubs. Trying to save them this way is as futile as saving Siberian tigers by breeding them in zoos, while their habitats in Siberia are vanishing.

If aboriginal dogs

continue to be used and bred for hunting or other

traditional service in countries of their origin

or elsewhere, they could survive and remain with

us indefinitely. Pauloosie Kooneloosie with his dog team after a seal hunt on the sea ice north of Qikiqtarjuaq, Nunavut. May 2001 Photo: P. Mahoney |

Preservation of hunting and other actively performing cultured breeds is more hopeful. There are many good strains used and selected for active performance specific of the breed. Using several strains of one breed for periodic genetic exchange would be helpful to maintain heterozygosis. A major obstacle in preservation of hunting dogs is the shortage or even absence of land and game for hunting. If we want to save hunting and other physically performing dogs as national heritage of humankind, lands for hunting with dogs are needed. This can be easily done without hurting wildlife communities, because traditional species hunted with dogs are usually abundant in every suitable habitat, are not threatened by extinction and they easily rebound. Even the wolf, if its populations increased to a sustainable level, can be hunted with Borzois, Staghounds and Taigans. It is debated whether or not the Chart Polski and the Hortaya Borzaya, popular among Russian hunters, are different breeds. They are very similar, except in one meaningful in evolutionary sense which is obvious. The Chart Polski is a show-pet breed, but the Hortaya is a hunting breed. To save the Chart Polski from degeneration its breeders and users have to be hunters. Dog breeds developed for active performance should avoid crossbreeding with show-pet strains to avoid genetic contamination by hereditary ailments. Bad genes do not fade away, do not become absorbed or eliminated except by patient line breeding and culling. To avoid this time consuming work, it is better to stay away from show lines.

Feral populations of dogs founded by cultured breeds also deserve preservation. They are biologically superior over pedigreed strains of show breeds and are valuable for evolutionary studies and as a potential source of healthy and intelligent puppies to be kept as house pets and as service dogs in different capacities.

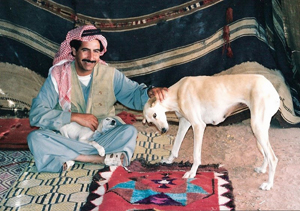

Taken in Jordan Picture donated by Sir Terence Clark

Allen, G. M. 1920. Dogs of the American Aborigines. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, LXIII, 9. Cambridge, Massachusetts: 432517 and 12 plates.

Beregovoy, V. H. and J. M. Porter, 2001. Primitive Breeds-Perfect Dogs. Hoflin Publishing. 424 pp.

Budiansky, S. 1992. The Covenant of the Wild. Why Animals Chose Domestication. William Morrow and Company, Inc. New York. 190 pp.

Coppinger, R. and L. Coppinger. 2001. Dogs. A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior, and Evolution. Scribner, New York, London, Toronto, Sydney, Singapore, 352 pp.

Corbett, L. K. The Dingo of Australia and Asia. Comstock/Cornell, Ithaca and London. 200 pp.

Das, G. 2009. The Indian Native Dog (Indog). PADS Newsletter, No. 21.

Gallant, J. 2002. The Story of the African Dog. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Gallant, J. and Edith Gallant. 2008. SOS Dog. The purebred Dog Hobby Re-examined. Alpine Publications.

Meggitt, M. J. 1965. The Association between Australian Aborigines and dingoes. In: Man, Culture and Animals. Ed. by A. Leeds and A. P. Vayda: 1729.

Mitton, J. B. 1997. Selection in Natural Populations. Oxford University Press, 240 pp.

Olsen, S. J. and J. W. Olsen. 1977. The Chinese wolf, ancestor of New World dogs. Science, 197: 533-535.

Pal, S. K. 2005. Parental care in free-ranging dogs, Canis familiaris. Elsevier, Applied Animal Behavior Science, 90: 31-47.

Savolainen P, Zhang Y-P, Luo J, Lundeberg J, Leitner, T. 2002. Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Science 2002:298, 1610-1613.

Sedefchev, A. and S. Sedefchev. 2009. The Karakachan Dog. Preservation of the aboriginal livestock guarding dog of Bulgaria. PADS Newsletter, No. 18.

The Natural History of Inbreeding and Outbreeding. Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. 1993. Thornhill, Nancy Wilmsen, Editor. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London. 575 pp.

Wayne, R. K. 1993. Molecular Evolution of the Dog Family. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. Vol. 9, no. 6.

Vladimir

Beregovoy

graduated from Perm State University as a

biologist in 1960. He defended his dissertation in

1964 and was awarded a Degree of Candidate of Sciences

from the Institute of Biology, Uralian Branch of

Academy of Sciences of the USSR, where he worked as a

zoologist. He taught at the Kuban State University,

Krasnodar. During his work as a zoologist, he traveled

to Ural, West Siberia, Volga River region, Kazakhstan

and North Caucasus.

Vladimir

Beregovoy

graduated from Perm State University as a

biologist in 1960. He defended his dissertation in

1964 and was awarded a Degree of Candidate of Sciences

from the Institute of Biology, Uralian Branch of

Academy of Sciences of the USSR, where he worked as a

zoologist. He taught at the Kuban State University,

Krasnodar. During his work as a zoologist, he traveled

to Ural, West Siberia, Volga River region, Kazakhstan

and North Caucasus. In 1979, Beregovoy immigrated with his family to Vienna, Austria and in 1980 to Oregon, USA. He worked on series of research projects in North Dakota State University and in 1989 accepted a position as Senior Agriculturist in the Department of Entomology, Oklahoma State University, where he worked until retirement in 2000.

From 1991 to 1996, he imported five West Siberian Laikas, three males and two females, as the foundation stock of this breed, newly introduced in North America. Currently, he is retired and lives with his wife, Emma, and their favorite Laikas on a small, 90-acre farm in Virginia.

Beregovoy has published several articles in popular magazines and two books: Primitive Breeds-Perfect Dogs and Hunting Laika Breeds of Russia. He is also the advisor and curator of the Primitive and Aboriginal Dog Society (PADS) as well as a member of the editorial board of the PADS Newsletter.