From the Editor: The Season for Sharing and Giving

Investigation of the pre-Columbian Ancestry of Today's Dogs of the Americas

Raising Eskimo Dog Puppies for Use in a Fan Hitch

Stareek and Tsigane

In the News

Baker Lake, Nunavut and the Canadian Animal Assistance Team (CAAT)

The End of the Beginning: The First Five Years of Veterinary Services in Baker Lake, Nunavut

Fan Mail

Book Review: The Meaning of Ice

IMHO: Finding Purpose in Retirement

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

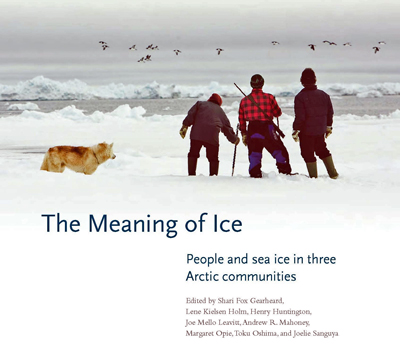

Hunters at the floe edge off Pond Inlet, Nunavut, 2008.

photo: Gretchen Freund

The Meaning of Ice

People and sea ice in three Arctic communities

edited by

Shari Fox Gearheard, Lene Kielsen Holm, Henry Huntington, Joe Mello Leavitt,

Andrew R. Mahoney, Margaret Opie, Toku Oshima and Joelie Sanguya

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

“If you were born by the sea ice, played as a child on the sea ice, raised a family of your own on the sea ice, depended on it, worked with it, think and dream about it, day in and day out – how do you describe such an integral part of your life, something exotic to most people, but familiar to you? Through the words, pictures, artwork, stories, and ideas of Inuit, Inughuit, and Iñupiat, this book tries to provide a first-hand account of the meaning of sea ice to Arctic communities. Of sea ice itself it shares great depth of knowledge, but more importantly, it shares ways of knowing, and what knowing sea ice means to those who live with and from it.”

(page xxxiii)

In The Meaning of Ice three closely related polar cultures and their communities are intimately chronicled: Iñupiat of Barrow on Alaska’s North Slope on the Beaufort Sea; Inuit of Kangiqtugaapik (Clyde River) on the east central coast of Nunavut, Canada’s Baffin Island on Baffin Bay; Inughuit of Qaanaaq in far northwest Greenland at the southern entrance to Smith Sound.

This book, actually better thought of as a comprehensive reference journal or encyclopedia, is the result of an undertaking that took place in these three communities between 2006 and 2010. The Siku-Inuit-Hila (Sea ice-People-Weather) Project drew together aboriginal people and scientists to “exchange knowledge, experience and skills related to sea ice...to better understand the dynamics of human sea-ice relationships...to characterize sea ice and its use by people...to document changes in the sea ice, consequent impacts on human use, and the human response to these impacts.”

Following the fascinating contributor bios (representing a diverse background, many originally from and/or currently living in the circumpolar North with upbringing in subsistence hunting, fishing and dog teaming) and generous sections devoted to the three polar communities, The Meaning of Ice is thoughtfully organized (all of which has been explained to the reader) into four main sections: the sea ice as “home”, “food”, “freedom” and “tools and clothing”.

Images in The Meaning of Ice include human portraits; beautiful paintings; archival and current photographs of landscapes and seascapes, communities and people engaged in activities on the sea ice (including a generous selection showing dogs at work); drawings; diagrams of the anatomy of animals harvested for food, fuel and tools; illustrations of the seasonal hunting/harvesting cycles of various hoofed, finned, winged and other animals and sea plants; diagrams of how animal skins are cut to make clothing; lists of terms, definitions and aboriginal names of sea ice tools; diagrams of dog harnesses, traces and qamutiit; descriptions of the various forms and conditions of sea ice are illustrated and explained.

Over forty contributors write about their past and present knowledge of and experiences with the sea ice as home, food, freedom and the creation of tools and clothing. Readers craving accounts of life in the words of the People themselves will especially appreciate the vast quantity and diversity of stories included. And those interested in the role that dogs played in arctic survival will particularly enjoy the references to this subject including Kangiqtugaapik resident Joelie Sanguya’s boyhood recollections of hunting polar bear by dog team:

“...Sometimes our fathers used to qaqqaliaq (go to higher place likes rocks on the land, or icebergs for good vantage points) to scan an area for any animal they could find. If they saw a polar bear, they tried not to come back to the dogs in a hurried manner, or talk about it when they were near the dogs, so the dogs would not know they had seen a bear. Many times though, the dogs did find out about what was going on, probably from our fathers’ energy, and the dogs would start to get excited...As we near the polar bear and the tracker dog, we can now hear the dog barking. My father unleashes the other dogs and we keep going on the qamutiik with the momentum. Then we finally stop, too close to the bear for my comfort. Dogs encircle the bear with what seems to be like music, as the dogs bark at the bear with a different tone in their voice than normal. One dog bites the bear from behind, and as it turns, another dog bites it from the other side...” excerpted from pages 120, 122The scope of this publication is truly overwhelming. Cover-to-cover, it provides readers with a far-reaching understanding of circumpolar life, past and present – from the perspective of the People who have occupied the North for millennia – that likely will not be collectively found elsewhere. Those of you who have an interest in polar culture and tradition (and dog team travel) will most definitely want to have your own copy!

At the publisher’s list price of $50.00 US, The Meaning of Ice: People and sea ice in three Arctic communities ISBN 978-0-9821703-9-7 (2013) – in hard cover and beautifully jacketed, 11.5” x 10.75” x 1.75”, with 416 pages, 645 color illustrations, 22 maps, 7 figures, 9 tables all in five-and-a-half pounds – is a bargain at twice the price! It is published by the International Polar Institute Press and distributed through the University Press of New England; also available through online booksellers. And with all proceeds from the sale of The Meaning of Ice: People and sea ice in three Arctic communities being directed to programs in the three communities described, the copy you purchase will have a special meaning of its own.