From the Editor: The Statistics of Sharing

Fan Mail

Contaminated Water! Yet Another

Long-standing Debacle in Iqaluit

Searching for the Shelters of Stone

How to Loose a Husky Team

A New Home for the BAS Husky Memorial Bronze Statue

Historical and Climatic Prerequisites of the

Appearance of the Population of Sled Dogs of the

Shoreline of the Chukotka Peninsula

The Sledge Patrol documentary update

Major Virus Issues in Canada’s North and

Canine Parvovirus Infects Inuit Dogs in

Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, 1978

A Decade of Service: The Chinook Project’s

2015 Labrador Animal Wellness Clinic

Inuk’s release in North America!

Book Review: Games of Survival: Traditional

Inuit Games for Elementary Students

IMHO: The Presumption of Good Faith

Index: Volume 17, The Fan Hitch

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The chimney top at Knutsbu Photo: Uren

Searching for the Shelters of Stone

by Gisle Uren

Thanks to the GPS on my phone, I know I am in the right place, but the stone hut that should have been right in front of me is nowhere to be seen. I have stopped the team thinking I will have to search the immediate area. Then I notice it, a little dark spot in the snow about 20 meters further ahead. I start the team forward, directing my lead dogs Trym and Nalle towards the spot. I have found it, Knutsbu, a little stone hut in Hardangervidda National Park. Only it isn’t in front of me, it’s below me. Buried under three meters of snow. The dark spot I have seen is the top of the chimney barely sticking out of the snow. It’s time for lunch, so we take our break practically on top of the hut while contemplating if it’s worth the effort to excavate to find the door.

Hardangervidda

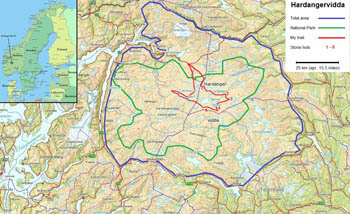

It is late April and I am on Hardangervidda on a five-day solo trip with my eight Greenland Dogs. Hardangervidda is a mountain plateau ("vidde" in Norwegian) in central southern Norway. Perhaps calling it a high mountain plain is more accurate because Hardangervidda is the largest plateau of its kind in Europe. It has a cold year-round alpine climate and one of Norway's largest glaciers, Hardangerjøkulen, is situated here. The plateau itself covers an area of about 6,500 square kilometers and has an average elevation of 1,100 meters. Approximately half of Hardangervidda is protected as a national park.

Hardangervidda has had human occupants for thousands of years and several hundred nomadic Stone Age settlements have been uncovered in the area. Ancient trails cross the plateau, linking western and eastern Norway and more recent historic stone huts and shelters are quite abundant across the whole plateau. Visiting some of these stone huts is partly the goal of this trip.

Stone huts

My primary goal is as always my love of experiencing the great outdoors in the wintertime with my dogs. The stone huts are a nice incentive though and help me choose the route for the trip.

The huts are from many different eras, some of them nearly ancient, some of them more recent. There is a variety of reasons behind the huts: giving shelter to travelers and traders following the ancient trade routes, shelter for shepherds, reindeer herders, hunters and so forth. They also vary greatly in size, shape and location. My plan is to visit four or five of them during my journey and if possible sleep over in a couple of them as well. The majority of the larger stone huts are privately owned and used as holiday cabins both winter and summer time and for the most part locked. Many of the smaller and more primitive ones though are open and stocked with firewood, a welcome haven for weary travelers.

It’s still early in the day, so I decide it isn’t worth the effort to dig my way into Knutsbu. I look at my map and take a new compass bearing before heading for the area of the next cabin on my list.

Arriving at Muran Photo: Uren

Traveling on Hardangervidda is comfortable this time of year. The terrain is gentle and the strong winter storms have made the snow compact and firm, making sledding easy for both the dogs and myself. The spring days are also long, the sun high in the sky and the temperatures are mild.

I have twelve year-old Trym my most experienced and attentive lead dog in front along with his son Nalle. We move along at a steady pace and I can direct the dogs right or left as I please. Trym is an experienced wilderness traveler and seems to almost intuitively know where I want to go. As I skijor along behind the sled I feel the worries of everyday life lifting off my shoulders. I take a few deep breaths and feel like the most fortunate person in the world.

Mountain trip or arctic expedition?

Going on a winter trip in Norway’s mountains necessitates bringing along much of the same equipment you would on an arctic expedition. The conditions can be quite horrific when a storm hits, so it’s important to have safety margins on my side. This means my sled is well filled and heavy, but I am still below what I consider the breaking point between weight and efficient speed. Over the years, I have found that if I can keep the weight of the sled to no more than 30 kg per dog, we move along at an even pace over almost any terrain. A heavier load than this means considerably tougher traveling in softer snow or over steep terrain.

As I am traveling Nordic style, skijoring along with the sled, I can add or remove my bodyweight as I feel is necessary to either help or slow down the dogs. Three of my eight dogs are ten years or older, so being able to slow down the younger ones is sometimes needed. My oldest, Edda, is actually just a few weeks away from her thirteenth birthday. I have built my team slowly and I now have four generations with me this season. Edda, her daughter, granddaughter and great-grandson.

The door at Muran Photo: Uren

Hut number two

In the early evening I arrive at the next hut, Muran, with the anticipation of sleeping indoors. As I cross the lake Geitvatnet I see the top of the hut well above the snow so everything looks promising. I stop the team, remove my skis and walk the few meters to the cabin hoping to find the entrance unblocked. I find the door easily enough, but only to discover someone has left it ajar. Whoever was here before me has not bolted the door and it has been blown open during one of this year’s frequent snowstorms.

I peek through the crack and find the hut filled with a big snowdrift covering the floor, table, chairs and even the lower two bunks. I don’t even consider starting to dig my way in. After looking around the area for a bit, I find a nice place to make my camp for the night. As I start the dogs towards the campsite, Edda feeling her workday has been long enough gives me a reproachful look telling me exactly how little I am worth to her right now. Having gone more than 35 km with a well-loaded sled today and as always Edda doing her best, I have no trouble understanding her. As I stop the sled after a only a short distance, pull the stakeout chain from the sled and start digging holes for the dead-man anchors, we make up and are friends once more.

After staking out the dogs, I quickly pitch the tent, unpack the sled and tend to the dogs. I spend some time with each of them thanking them for their help today, rubbing their tired muscles and checking their paws. After feeding them, I take a few pictures of our camp and the surrounding area before retreating to the tent to make my own meal. Before entering my tent, I look at the beautiful light of the setting sun reflecting off the three distinct mountain tops Melrakknutan. “Melrakk” is an Old Norwegian name for arctic fox; “nut” is a Norwegian word for peak.

My camp in front of Melrakknutan Photo: Uren

To my surprise, on this trip I seem to find the tent much smaller than I remember from previous years. I use this tent mainly for solo-trips and it is several years since I’ve used it. I know the tent can’t have shrunk and I know I haven’t grown. I do however discover that over the years I have more than doubled the amount of gear I bring along. The advantage or perhaps disadvantage of sledding with a larger team becomes very clear. I have also adopted the practice of packing much of my “inside the tent” gear in two plywood boxes. Very practical in keeping everything organized, but they do take up quite a bit of room. I fall asleep that night wondering if I should either rethink my packing regime or simply buy a bigger tent before my next solo trip instead. We’ll see, we’ll see.

Reindeer

There are many appealing things about Hardangervidda. Its size, its elevation and its polar climate are some of them and thanks to these, its fauna as well. One of Hardangervidda's most exciting animals are the reindeer. Norway has Europe’s last remaining wild tundra reindeer with an estimate of about 25,000 animals. The largest herds, about 6,000-7,000 animals at present, are found on Hardangervidda. Reindeer migrated here following the gradually receding ice sheet about 12,000 years ago.

Interestingly Norway’s reindeer show genetic evidence of having migrated from two different areas. The reindeer on Hardangervidda and surrounding areas have migrated from the south (mainland Europe) while reindeer found further north have migrated from the east (Beringia). Neither of these two areas were glaciated during the last ice age and both had large herds of reindeer as well as other animals.

Gradually groups of hunter-gatherers followed in the footsteps of their main prey, reindeer. Today reindeer pits are found all over Hardangervidda and other mountainous areas of Norway. These are stone pits used for trapping reindeer and are normally accompanied by leading fences or walls, also made from stone, which would have guided the animals towards the pits. In some areas one can also find bow rests - stone built hiding places for hunters equipped with bow and arrows.

Team photo at Knutsbu Photo: Uren

Hut number three

After short hours sledding the next day we pass stone hut number three on my list. Bakkehytta, the hut on the hill, is as its name implies situated quite a bit up a hillside. I’m glad I didn’t continue here last night because there is quite a distance from the hut to where I would have had to leave the sled and stake out the dogs; either that or have a suicidal start from outside the hut the next morning. From the location of the cabin, overlooking a small valley with a few small lakes, I feel that this has perhaps been a hut used while hunting and fishing in the area in the past. To support my assumption I find on the map that the lakes are named Feitfisktjønnan, Fat Fish lakes. This must be a good place to stay in the summertime.

As I turn the team around and head west, the dogs notice a fox crossing the valley in front of us. It gives a warning bark and speeds up the side of the mountain where it from a safe perch looks down to see if we follow or not. The dogs are more than willing to give chase, but I boringly opt for continuing in our planned direction. Sadly, this was a red fox that has replaced the now quite rare arctic fox.

Once Hardangervidda had a large population of this fascinating winter white fox, but as a result of massive trapping they became nearly extinct. In spite of having been protected since 1930 the population is still dwindling. Norway and Sweden have both started programs to try to help the arctic fox to repopulate its former habitats. Hardangervidda is one area where foxes have been released in recent years, hopefully to settle, thrive and repopulate this great mountain area.

Mother Eqqo (L) and son Branoq (R) Photo: Uren

Marked trail

I continue towards the next stone hut and after a while come to a marked ski trail between two of the Norwegian Trekking Association's cabins. I am a little surprised to find it still marked this late in the season. Normally the trails are marked from a few weeks before to a few weeks after Easter. The good thing is I don’t have to look at my map quite as often to find my way, the bad is I lose some of the wilderness feeling I have had until now. I could always choose a different route, but the marked trails usually follow the best and most logic routes between different areas. As I am looking for specific stone huts, these are also often situated along these same routes.

The trail markings are thin, straight saplings of birch, ash, roan, willow and possibly a few other species I don’t recognize from their bark. They are two to three meters tall and supple enough to hold up well in the strong storm winds, although sometimes they need to be replaced because they are buried by the accumulating snow. The saplings are also preferably at least one year old before they are used. Fresh saplings mean frequent replacements because reindeer find them very tasty and eat them as they pass along.

The trail I am following passes Lågaros, both the name of a Trekking Association cabin and the source of Norway’s third longest river, Numedalslågen. Norway is a mountainous country and most of our rivers are steep and short, and Numedalslågen, though being a good river for salmon fishing, is only 359 km long. Lågaros is also the location of Råstugu, the fourth hut on my list. This is a nice sized dwelling with four beds, a table and a wood-burning stove. I consider stopping here, but it is still fairly early in the day so I continue for the fifth and last stone hut on my list.

Elk Lake Hut

After a short rest outside the Trekking Association cabin Lågaros, I continue towards the stone hut Elsjålægeret. The name of the hut would translate into Elk Lake Hut in English. Though we are fairly high in the mountains, Hardangervidda has a large number of the animal known as elk in Europe and moose in North America that graze on the lush vegetation during the summer.

As I get close to where the cabin should be I get a feeling this one might be snowed in as well. There is no hut in sight as I cross the lake Elsjåen. But I do see a small cairn like structure, almost resembling an inuksuk. As I get closer I see that it is actually the stone chimney of the hut I have spotted. My premonition was right. Elsjålægeret is almost completely buried in snow. I want to sleep in at least one stone hut on this trip, and having passed up two other huts today, this is my last chance. I have to start digging. But where do I start?

From the roof ridge protruding from the snow I can tell that this hut is quite small. I make an educated guess that the door is placed at the same end of the hut as the stove, leaving the other end free for bunks. I start digging and about 50 cm down I find the top of the door. A while later I uncover the first hinge and keep digging. After another 50 cm I find a second hinge. I have lucked out, the door is divided into two separate wings. I only have to dig half as deep as I first feared.

Elsjålægeret and the upper half of the door placed on the roof Photo: Uren

Breaking and entering

After the top half of the door is clear, I find it has no door handle. There is a small brass bolt lock, but no handle. The door is jammed shut and due to moisture it has swelled so there is not even a slight crack between the door and frame.

Someone has most likely been here earlier this winter and pulled the handle off the door trying to get in. There are now only two screws with the pointy end sticking out of the door where there once was a handle. I try prying the door open with my limited amount of tools, an axe, a shovel, a knife, a pair of pliers, a couple of screwdrivers, etc., but nothing lets me get enough grip or leverage to open the door.

I find the handle in the pile of snow I have removed. It is made from the bend of a Juniper branch. The screws sticking out of the door seem to be firmly fixed so I make an attempt of re-screwing the middle of the handle to the door. I then grab both ends of the handle and gently increase pressure until suddenly the door pops open.

Feeling like part cat burglar and part mole, I crawl inside the upper half of the door to look inside. Most Norwegian huts and cabins have a book/journal where visitors enter their name, date of visit and most often a short account of their journey or something else you would like to share. From the book at Elsjålægeret I see that no one has been here since late September, seven months ago.

Warm spring evening

Nearly everything inside is covered in a centimeter thick layer of hoar frost. After removing it and lighting a fire in the stove I go back outside while the hut is drying out and warming up. I find a bare patch of ground behind the hut and spend a few hours in the slightly warm gradually setting spring sun. I bring my thermos, a large bar of chocolate and a few booklets containing reprints of old traveling journals and articles from Svalbard.

Enjoying the evening sun Photo: Uren

Rock ptarmigan males singing from the snow covered mountainsides set a perfect wilderness mood. Mating season is getting close and they have all claimed their own little spot of bare turf, singing to ward of other males and entice the females to join them. Singing is a term used quite liberally; it is more a low guttural clucking and rattling than a song. Rock ptarmigan have a very distinct sound which is quite enchanting to listen to.

As the sun dips beneath the mountains to the west, the air gets a bit nippier so I take a few last pictures and retreat inside my now warm and slightly less damp shelter of stone. To mark the occasion I have brought along a nice piece of reindeer tenderloin, vegetables and Norwegian almond potatoes. I’ve even brought along a portion of chocolate pudding for desert.

The food is delicious but what makes the evening even better is the knowledge that I am only half way through my journey and still have several days before I reach my car.

Just in time for a late lunch

On my last day out, as I get closer to Dyranut where I parked my car, I find myself taking more and more frequent breaks. It’s not too warm and the dogs aren’t really tired but I simply don’t want the trip to end. Any excuse to prolong it is welcome. Speaking of the dogs, they have been exemplary the whole trip, calm, attentive and hard working. As close to a perfect dog team as I will ever get.

The kilometers pass by relentlessly though and much sooner than I hope I suddenly see Dyranut as we climb what is clearly the last ridge. The Trekking Association cabin Dyranut takes its name from the small peak behind it. The name Dyranut suggests that this small peak once was a good spot for reindeer, reinsdyr in Norwegian, Deer Peak.

The dogs see kite skiers for the first time in their life Photo: Uren

As we get closer, I see a number of kite skiers tacking back and forth in the head wind. Naturally, they both need and love the open and windy areas found here as much as mushers do. My dogs, seeing this activity for the first time in their lives, are keenly fascinated. As their initial excitement wears off and the kiters are recognized as non-edible, I use this as my last excuse to make a stop. I take some pictures and spend a few minutes planning how to navigate my way to the parking lot. As a precaution, I move young Branoq to the back of the team and move reliable old Viking a few notches forward. Branoq is young and curious. Viking is focused on pulling straight ahead.

About 100 meters from the parking lot there are two kiters sitting in the snow just a few steps to the side of the trail. I think to myself they’re probably untangling their kites and preparing to start off again. Then, when we are too close to stop and just as my lead dogs are passing them, I see that they are actually eating lunch. I feel a sense of dread as almost in slow motion I see all my dogs veer off the trail and pounce on the two perplexed and panicking kiters. Always observant Viking takes a lunge in between them and comes back out with most of their remaining lunch in his mouth. Brilliant idea to move him to the front of the team, I think to myself.

I drop anchor, unhook myself and quickly straighten out the tangle of dogs and kiters. I then pry Vikings mouth open and grab hold of what just a few seconds ago I think was bread, cheese and red bell peppers in a plastic bag.

With the team back in order I head over to the kiters with the soggy red and white lump in my hand. I look at it for a few seconds and know it’s no use even trying to give it back. I just turn around and stuff it into my sled before they get a good look at it. I then apologize to them the best I can and offer to repay them for their lost food.

Luckily they are more relieved than angry. They even say they were almost finished eating anyway, so it was no big deal. Now that they no longer feel their lives are at risk, though not quite able to laugh about it, they assure me it was even worth the experience as they now have a great story to tell their friends. I apologize again, try my best to look contrite and continue on the last bit to my car.

As I pull out of the parking lot a while later, I see them kiting happily back and forth in the distance. I can’t help but laugh a little at the absurdity of the situation. It’s a beautiful day, you’ve been kiting all morning, you’re enjoying your lunch in the warm sun, admiring the beautiful dog team passing by when suddenly before you can react you find yourself in the middle of a pack of frenzied dogs – dogs you don’t know if they're attacking you or not; dogs that are much too big and strong to be pushed aside; dogs that are eating all your food…and then the great relief you feel when the dogs all just end up licking your face instead of eating you!

This must be the most uncivilized return to civilization I have ever made. So much for my perfectly well behaved dog team.

Gisle Uren, his partner Anne and their three children live outside Roros, Norway. One of Gisle’s great passions is outdoor - especially winter - activities. For more than 20 years he has been going on trips of varying distances in the Norwegian mountains. He bought his first Greenland Dog in 1998 and now has a team of eight adult dogs.