From the Editor: A Kaleidoscope of Activity

Is there a vet in the house?

The Sledge Patrol update

In Search of John Flick

My Life with Dogs

Canadian Inuit Dogs I have owned, raised and trained:

a photo essay; Part 2

Inuk VOD Release

From the NFB Archives: How to Build an Igloo

Film Review: People of a Feather

IMHO: What Do You See?

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

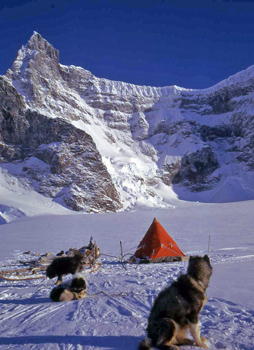

My team the "Ladies" at Snick Pass, the head of the Grotto Glacier on Alexander

Island, with the Antarctic Peninsula in the background. Isolde as leader, Sue (white)

and Tramp (black) as first pair, Konga by himself (a Greenland import in 1971),

Sid and Dave, Andy and Wolf (hidden) as back pair. The missing dog was transferred

to my colleague when he lost a dog down a crevasse, making his team under-powered.

Photo: Edwards

My Life with Dogs in Antarctica 1972-75

by Chris Edwards

When I was a child my knowledge of dogs was limited to a brown miniature poodle, then a black one, then a white one. Quite intelligent dogs in their way, apparently bred as hunting dogs, but it was hardly training for what was to follow.

I first went to Antarctica as a young earth scientist in late 1972 and had no thought of dogs. My first summer work season was the first time the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) dared to try snowmobiles in the field in areas potentially dangerous with crevasses, and away from the solid ground around a base hut. We survived crossing glaciers unscathed despite sitting astride our own personal crevasse probes. However, trying to perform the necessary servicing on a vehicle in temperatures of -10°C and lower was a chore, especially when hot soapy water was not easily available. With an unmodified simple push throttle on the handlebars, “skidoo-drivers thumb” was a constant uncomfortable hazard.

At the end of that first summer I was transferred to Stonington Island, which lies at 68° 11’S 67°00’W near the southern end of the Antarctic Peninsula. This small island contained the main field operations base for the BAS and because of its location there was easy access onto the Antarctic Peninsula via a snow ramp from the island up on to the surface of the Northeast Glacier and thence to the whole of the continent.

The island (0.8 km x 0.3 km) had been home to a number of expeditions through the 20th century: the United States Antarctic Service Expedition’s East Base hut dating from 1940 was reoccupied by a private US expedition in 1947-8 led by Finn Ronne, contemporaneous with a Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS, later BAS) base which had been established two hundred metres away in 1945. Ronne had brought aircraft and heavy tractors, as well as dogs from Chinook Kennels, Wonalancet, New Hampshire but about half of his 43 dogs had perished from distemper on the way south. The survivors had been supplemented by a motley selection of dogs supplied from the streets of Valparaiso by the local police, including a hairless whippet! The tractors were unsafe in the local terrain but after a bit of local rivalry, the Americans and the British co-operated with the dogs and aircraft allowing more productive work. The British dogs had been sourced in Labrador and been brought south with the expertise acquired in Greenland by some of the team members. They formed the roots of what was to become a huge dog family tree, which, unbeknown to me at the time, I was to witness and be part of its’ withering, thereby breaking that last link with the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration which stretched back to the first use of dogs in Antarctica by Borchgrevink in 1899 and Nordenskjöld in 1902.

Andy, a stunning dog with a thick coat.

Photo: Edwards

A BAS dog was typically stocky in stature, with a deep chest and capable of pulling a fully laden sledge of 350-450 kgs. for 8 hours a day with a 5-10 minute rest every hour or so. The dogs weights were typically 30-45 kgs. Their multi-coloured coats varied from very long staple to short hair but all with a dense undercoat which allowed them to overwinter outside in temperatures as low as -30ºC and wind speeds sometimes in excess of 100 knots.

Arriving on base with the relief ship, there was much to be done: hails and farewells, moving stores inbound and outbound, exploring one's immediate surroundings and saying hallo to the huskies. Over the next few days base life settled into a routine but the ever present dogs had to be fed and cared for as well as new drivers introduced to their teams.

Those times are a bit of blur now but a diary does help. About 150 dogs were spanned up on the surface of the glacier five minutes walk from the base hut, and at first sight seemed a ferocious group, fortunately all secured by a stout chain to a wire hawser secured firmly in the ice. Later I would realise that you were more likely to be exuberantly licked rather than bitten. The noise was intense with stifled barks but the most haunting sound occurred when the random noise would gradually die away to be replaced by one dog starting a howl to be joined by all the others. The howl would often stop quite abruptly as if choreographed by an unseen conductor.

Learning to drive dogs efficiently was not easy for a novice. With no instruction manual to refer to and perhaps only the briefest of handover notes or incomprehensible comments from the outgoing driver, it was very much a case of trial and error with, hopefully, a helping hand from an experienced sledger starting his second year.

At Stonington it was normal to run nine dogs in centre trace formation i.e. four pairs and a lead dog out front capable of responding to the simple commands. Of course there were other ways to harness dogs to a sledge – the fan and modified fan being the most common. Apparently the centre trace system was used in areas where trees were present but it had the advantage in not having a huge tangle of rope to sort when dogs changed their running position. The sledge was invariably a twelve-foot long Nansen, made of ash and lashed together with linen cord or rawhide, making a flexible all-terrain vehicle. A more rigid sledge running over sastrugi (a wind-sculpted snow surface) would likely suffer breakages. The runners were shod with a cloth-based phenolic resin board, which provided a low-friction bearing surface. The driver ran, skied beside or, (rarely) stood on the extension of the runners at the rear by the handlebars. For man and dog to get the most enjoyment out of the experience required an understanding of dog psychology and a keen observation and interpretation of interactions between team members. Huskies have two main aims in life: to pull sledges and to have a good scrap (when the boss isn’t keeping a watchful eye) in order to assert ones authority over ones neighbour. With using the dogs almost every day, I estimated that becoming a passably proficient dog driver, as well as necessarily physically fit, took about six months.

Exploring along a windscoop (the wind whistles round a rock outcrop

and prevents snow accumulation) Photo: Edwards

The first few weeks with a new driver behind an existing team of dogs would tend to be a relatively straight-forward honeymoon. But gradually it would dawn on those dogs that the voice behind the sledge was different, and that they could get away with bad behaviour much more than they could with their previous human boss. Unless this feature was recognised and acted upon swiftly by the new and probably inexperienced driver, the situation would quickly deteriorate until chaos reigned and mass fights would ensue with nine dogs all in a tangled snapping mass. With acute observation of the attitude of dogs towards one another – the slope of the ears, tail and head and how they walked past and presented themselves to each other – one could stop a fight even before it started, making for less stress and less time spent dressing and stitching up puncture wounds or torn ears. But of course to recognise the signs took practice. I did not subscribe to the notion of the alpha dog as the pack leader keeping the others in order. The driver had to be the “king dog”.

Worldwide, dog driving commands are simple, but I have seen a whole lexicon of unnecessary commands offered as “the” way to drive dogs. The BAS commands probably originated in Labrador and may have been modified during usage but there was nothing magic about any command structure other than it had to be sufficiently distinctive to the dog’s ear, and be presented to the dogs authoritatively. To go right it was a sharp “Owwk! Owwk!” (as in owl with a “k”). To go left was quite different and made by rolling an “r” by vibrating your tongue into an “Irrrrrr-a! Irrrrr-a!” Of course this required a little trial and error and it was amusing to hear some drivers first attempts. One wonders what the dogs made of them! My leader, Isolde, who I trained up, would respond to “Owwk-a-bit” or “Irrra-a-bit” if I wanted to make only small course corrections. Stopping was accompanied by an “Aaaah, now” said softly and applying the brake at the same time. Starting off rarely required any command, especially first thing in the morning, but if anything was needed then a push of the sledge to un-stick it from the snow and a “Hup, dogs, Hweet” or other similar encouragement usually sufficed. Infractions were greeted with a long “Noooo!” and a correct interpretation of commands with an encouraging “Yes, yes”.

During long journeys on the Antarctic Plateau up at around 1500 metres with perhaps only very distant mountains to aim for and nothing to smell, most teams would tend to get a little bored as a dog’s eye height may mean only a limited horizon. Tails would droop, the speed would slow and the general demeanour of the team would be lethargic. To stimulate more effort drivers would resort to making curious noises, singing songs or performing other tricks which would help. Then tails would go up, ears would perk up and the dogs would turn, look at the driver to see what the silly noise was all about and trot on. A normal field party would consist of two men, two dog teams and one tent. The travelling regime would alternate daily as to who would lead and break trail. Loads on the sledges would be adjusted to make the leading sledge slightly lighter than the follower.

Each dog had an individual cotton lampwick harness made and fitted by the driver. Lampwick was softer than the nylon webbing often used today on commercially produced harnesses. The design was simple and consisted of a neck hole and two leg loops, which crossed over the chest and fed back to a D-ring on the back. The centre trace sections were about five metres long nylon rope with a eye spliced loop in either end with similar one metre long side traces. Splicing rope was another skill to be mastered. No neck trace (neck line) was used. Drivers were not prescriptive in insisting that a particular dog stayed on one side of the centre trace or other, but generally each dog had a preferred position. The members of a team were not “cast in stone” as dogs were swapped and changed due to injury, pupping, new pups being introduced etc.

Sledge wheel with Isolde, Sid, Andy, Sue and Dave. The sledge wheel

was our distance-measuring device. Photo: Edwards

Out in the field away from base the dogs were spanned at night, either on the main trace or on a thin wire line with short chain sections for those dogs prone to chewing nylon rope.

On base the feeding regime was based on 7 lbs. of seal meat and blubber (usually crabeater seal) every second day. Out in the field a pre-prepared 1 lb. block of dried and compressed meat, cereal and fat was fed on a regime of 1,1,2 on a three-day cycle. Depending on how much work the dogs were undertaking and the climatic conditions, some dogs lost weight and others remained fairly static. Any unconsumed butter in the man-food rations was distributed fairly and disappeared in a flash.

In mid-1974 a communiqué was issued by the British Antarctic Survey, which dictated that virtually all the travelling in future years would be undertaken with snowmobiles using aircraft to deposit summer-only scientists into the field adjacent to their work areas. As a result the nearly 160-strong dog population became surplus to requirements by the end of the 1974-75 summer field season. A decision to retain 42 dogs was insurance that, in the unlikely event that snowmobiles could not be operated safely, there was a nucleus of animals to recreate a number of teams. Most of the drivers knew in their heart of hearts that this was an extremely remote possibility and in reality this proved to be the case.

In one bloody afternoon a cull, using a .45 revolver, effectively destroyed the illustrious history of the dogs of the British Antarctic Survey, and gave me a psychological trauma which has taken years to come to terms with.

People often ask, “Why didn’t you bring them back to the UK or elsewhere?” Frankly, I was given no such option and in any case, Inuit Dogs are not family pets, though these were loyal and loveable. In contrast the Australian and New Zealand huskies were transported to and lived on in Minnesota.

Over the succeeding years from 1975 intermittent breeding did take place in the remaining population of 42 dogs and bitches. By the early 1990s discussions within the Antarctic Treaty nations centred around the possibility that phocine (seal) distemper could be passed from the Antarctic dogs to the seals as something similar was suspected in the northern hemisphere. This seemed highly unlikely as the dogs had been born and bred in Antarctica since 1946, and indeed transmission of a ringworm-like infection to, rather than from, dogs in the 1970s was thought to have originated in seal debris exposed during excessive melting of snow on Stonington Island. However, a decision was made that no non-indigenous animals or plants (except man himself!) was to be permitted in the Antarctic Treaty area (south of latitude 60°S). I asked the BAS if I could have one of the last dogs but this was denied. Consequently in 1994 the remaining 14 dogs, the ancestors of which had been moved from Stonington Island when it closed in 1975, at the British research station at Rothera Point, Adelaide Island were removed and flown via the Falkland Islands, Ascension Island, the UK and eventually to Canada. A small community on the east shore of Hudson’s Bay had been offered the dogs as a symbolic gesture to return them to their “ancestral home”. The denouement was not pretty – within six months half of the dogs that arrived in Canada were dead and the remaining six were taken to Toronto Zoo where a further four died. Someone who knew of their history and could provide them with the necessary facilities rescued the last two. All in all, a sad end to a glorious heritage and one which the modern science organisation of the BAS seem reluctant to acknowledge – donations from drivers and others enabled a bronze husky memorial to all the dogs to be erected in the grounds of the Cambridge headquarters in 2009, but has now found a more welcoming site at the Scott Polar Research Institute, also based in Cambridge. Fortunately, Kevin Walton and Rick Atkinson in Of Dogs and Men compiled some of the stories solicited from drivers who had run and loved the dogs through the years and this must be their epitaph.

Pyramid tent and dogs spanned out for the night.

Photo: Edwards

Further reading:

Darlington, Jennie. 1956. My Antarctic Honeymoon: A year at the bottom of the world. New York, Doubleday, 284 pp.

Edwards, Chris. 2015. Husky Man. Houndsounds.co.uk/huskyman.html. Transcribed in The Fan Hitch V. 18, N. 1, Dec 2015.

Ronne, Finn. 1949. Antarctic Conquest. New York, Putnam’s Sons, 299 pp.

Walton, Kevin. 1955. Two years in the Antarctic. London, Lutterworth Press, 194 pp.

Walton, Kevin and Atkinson, Rick. 1996. Of Dogs and Men: Fifty years in the Antarctic. Malvern, Images Publishing, 190 pp.

Chris Edwards is one of the last of the “Fids” (British Antarctic Survey personnel) to use dogs as a prime means of transport in Antarctica during two successive summers and winters. In February 1975, as the “doggy man” in charge of the veterinary work and breeding, he spared the other dog drivers and took on the dreadful task of having to cull over a hundred of the BAS dogs. He has had to live with that memory ever since.