Table of Contents

*

Featured Inuit Dog Owner: Brian and Linda Fredericksen

*

Lake Nipigon - Solo

*

Inuit Dogs in New Hampshire, Part II

*

The Inuit Dogs of Svalbard

*

Update: Uummannaq Children's Expedition

*

Update: Iqaluit Dog Team By-Law is Official

*

Poem: Instinct

*

The Homecoming: Epilogue

*

Product Review: Sock Sense

*

Tip for the Trail: Wet Equals Cold

*

Janice Howls: More Than Meets the Eye

*

Page from a Behaviour Notebook: Hunting

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The Fan

Hitch

The Fan Hitch

home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

by F. Murray Clark

as told to Mark and Sue Hamilton

"This is September 13, 2000 and this is a conversation between W. Murray Clark of Lincoln, New Hampshire and Mark and Sue Hamilton of Connecticut concerning the subject of Eskimo dogs which they would prefer to refer to as Inuit Dogs." We had traveled nearly 5 hours to this central New Hampshire town for the long anticipated interview. But W. Murray Clark quickly set the tone of our meeting with his opening statement. As it turned out, we were there with our tape recorder, not to hear W. Murray Clark answer a bunch of questions, but to listen attentively to his chronicle of the Clark family's involvement with "Eskimo Dogs", beginning over two decades before Ed Clark, Sr. imported his first one into the United States.

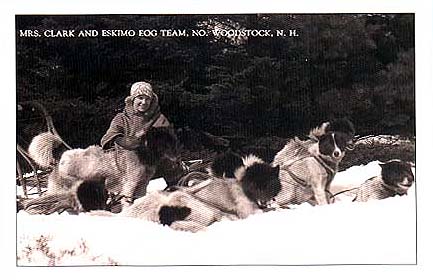

Clark Photo

Edward P. Clark, the son of a medical doctor, was born in Mamaronek, New York in 1888. He loved the outdoor life and enjoyed hunting and trapping. In 1908, at the age of 21, he began a fourteen-year career in the fur trade, taking his first ever job at the raw fur business his uncle Charles S. Porter was managing in New York City for G. Gottig and Blum, German international fur merchants. In 1917 the young Clark was sent by the firm to Labrador. The company's representative there was not responding to telegrams sent from New York inquiring about what was happening to the money he was receiving to finance his northern outpost nor was he shipping out any raw furs. Clark, exempt from the WWI draft due to a heart murmur, traveled to Cartwright, Labrador to meet with this non-communicative employee, audit his books and find out why he was not sending out any furs. He found that the factor was using the company funds to finance the captive raising of foxes and other fur-bearing animals for their pelts. This was the beginning of fur farming. He was also experimenting with the freeze storage of Ptarmigan and cod fish to see if they could be thawed out long after and still remain edible. But these activities, financed by Porter's funds, produced no tangible benefit to the New York division of the German fur merchant. And so the factor, Clarence Birdseye, was fired.

Within a few days of his arrival in Cartwright, Labrador, Edward P. Clark began to explore the area. "My father couldn't help but notice these rugged outdoor dogs with powerful shoulders and wonderful personalities. Within a few days he fell in love with these dogs, known as Eskimos or, to use the slang word, huskies. And in one of the pictures that he took just a few days after he got there, the dogs were seen not fenced, not collared, not chained, but running free. When the wife of the fishermen started to clean the fish and put them in to the barrel, the innards went down over the wharf and onto the rocks where the dogs were waiting. That was their meal. In the summer when there was no use for the dogs they were boated to an outlying island where they ate fish out of fish pools, ate ducks and duck eggs, and they had to fend for themselves. In the fall when there was snow on the ground the dogs were boated back to shore and then fed extra fish and oatmeal and dried seal meat to start to build them up for winter when they would have some long coats to stay outdoors and curl up in the snow."

Edward P. Clark established three trading posts in the name of his uncle, which were in direct competition with the Hudson's Bay Company's trading posts in the region. During his first winter in Labrador, Clark hired a driver and a team of dogs and traveled about 500 miles up the coast to Okak and Nain buying and collecting raw furs. He eventually made four trips to Labrador in about three years and in 1921, after establishing a former school mate as the manager of the Porter's Post in Cartwright, Clark returned for good to the States. "He married Florence Murray in New York City, in The Little Church Around the Corner, in October of 1922 and immediately headed out to some place in New England with a few Eskimo Dogs he had already imported from Labrador, expecting to find some place up here where he could raise Eskimo Dogs, sell some puppies and promote the breed and deal in raw fur in the winter time to make a living. They found a little farm in West Milan, New Hampshire. It had 15 acres, a barn a brook and a house for $2400. After buying the farm he arranged to ship the dogs up to the farm. He fed them beef and horsemeat, meat scraps from butcher shops and possibly dog biscuits and dog chow. To earn their own keep, he would take them by train to state and country fairs during the summer when possible, getting as far west as St. Louis, Missouri to state fairs. As he was having difficulty transporting them by rail, his father bought him a suitable stake body wooden platform truck to transport the dogs, the skin clothing and other curios from the north to display them. This done at the peak of the summer heat. He promoted Eskimo Dogs and entered sled dog races in the winter. He had a benefactor, W. R. Brown, in Berlin, New Hampshire who owned the big paper mills. He was an enthusiast of sled dogs and promoted racing and helped my father. My father and mother worked together and created a race from Berlin, New Hampshire to Boston, Massachusetts. My mother drive her dogs up the state house steps in Boston. They both took home trophies from that race."

"In the spring of 1928, after having been about 6 years on that farm and not achieving much success, a friend suggested that my parents relocate somewhere onto a well traveled highway where summer tourists could find them. So they headed south looking for farms for sale. They found themselves on route 3 in Lincoln where they bought a farm for sale with 90 acres of land on both sides of the main road. In thirty days after they moved down they had a little stand and 14 dog pens, 20' x 20', erected with cedar posts and then heavy chicken wire stapled to the cedar. In the yard during winter, the dogs were kept out on 11'6" chains attached to stakes, to keep them from running away and killing the neighbors’ chickens or getting struck by cars or killing the local household cats."

"As years went on, the original dogs died out. Occasionally we needed new stock. My father got some that had been with Grenfell, some that had been with MacMillan which I believe came from Baffin Island. That's where the black head stock came from. Some came from Greenland. We had to do that as years rolled on. This was the only Eskimo dog ranch in the country. Eskimo Sled dog Ranch - never a kennel. We didn't use that word. In 1928 my father became the president of the Eskimo Dog Club of America. My father entered some of his best at Westminster Kennel Club Dog Shows in New York City and he would come back with Best of Breed. One of his greatest admirers, or should I say admirers of Eskimo Dogs was Felix Leser of Saranac Lake, New York. He got stock from my father and had a team of our blood lines. My father would sell a pup here or there. I don't recall if more than one or two went to some other buyers who wanted one as a pet. My father sold pups without pedigree for $25. He sold pups with a pedigree and charged $25 more per pup. A common pup of six or eight weeks of age was $25. He was constantly writing letters and answering letters. By the time we had a litter of pups, the person who had written expressing an interest had found something else. Well, this was what happened when you raised to sell. They grew bigger very quickly. They're just like children. Now they had to be trained when they got to a certain age. And that's the problem we got into. The thing that held back my father's success and the family's success for many years was too many dogs. One time we had over sixty. And so, the things that kept us busy with Eskimo dogs were they had to be fed, watered, groomed washed, shown in the summer. In the very beginning we had an admission fee when we first opened in 1928. The idea of establishing a kennel, a ranch, a congregation of them to sell to the public, to have a guided tour to look at required a fee to help pay for food, electric bill, all the other things that came along. The first admission charged in 1928, July 10th or thereabouts was 25 cents per person. My father was the tour guide and my mother also was a tour guide. The first year they took in $1100 and they were ecstatic."

"In 1932 to gain more publicity for our Eskimo dogs my mother and my father and the neighbor's son decided to take the feature editor of the Boston Sunday Post and his photographer on an adventure up Mount Washington. I presume this was done in March. I don't know but there might have been seven dogs on that team - and four men and my mother. They got about two-thirds of the way up, within site of the summit, when the photographer started to complain that he was having trouble catching his breath. It was the elevation and the hard work. And so immediately they turned around and headed down to the half-way house shelter for the night."

"In April of 1932 my mother sent my brother and I to the next door neighbor down here to stay with her a few days. My father had to stay here to take care of the balance of the dogs. My mother took her prize team of five, with Clarkso in the lead, and went up Mount Washington alone. That trip cost her health, she frosted her lungs on the way down, and eventually was the cause of her death years later."

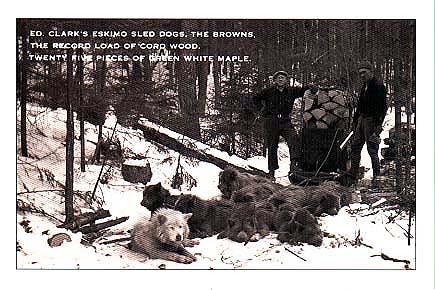

"My father had a freight team of browns, probably the like of them were never seen in Labrador because my father line bred to get this brown color. That was his prize freight team. Kovac the leader was the father and, later, the mother produced a litter of four medium hair and two shaggy. You see the Eskimo dog comes in the primary dog colors of white, which can also be buff or ivory, black and degrees of black, some of which are termed "blue" and it comes in brown (we called them browns, we never called them reds) which was the result of my father's line breeding. They also come in three coat lengths. There's short haired, there's medium and there's shaggy."

"My father's freight team pulled a sled weighing about 300 pounds and it was carrying 25 pieces of green rock maple weighing 1339 pounds. The dogs in the team were all males. That in itself was an exception to the rule. It was one thing for two females to be working together, but to have all males and be able to control them and rarely was there a fight. My father and mother did some exceptional things."

"The Eskimo dog is not the fastest sled dog in the world, but for sure it is the hardest worker with more strength and endurance, but at a slower pace. According to National Geographic back in the 1930s they are considered a "stone age" breed. My brother and I could go right out through the bushes with them, a team of three, and those dogs just loved to be in harness, and they loved to be out in the woods and they loved to fight! A good fight and afterwards their tails would be wagging! My brother and I, probably for Americans, had more experience with Eskimo dogs than any one of our age group. It was my life."

In 1936 Edward P. Clark needing new bloodlines, asked his former driver and guide in Labrador to collect some outstanding stock as well as locally made "curios" and to drive the team by fan hitch from Cartwright, Labrador to North Woodstock, New Hampshire. Still in Labrador on the way south, after acquiring nine "big boned and outstanding specimens", the driver passed through an area where distemper was rampant. Five of the nine dogs died and it wasn't until the following summer that the surviving dogs could be brought to New Hampshire.

In the spring of 1942, the British government purchased 24 of Clark's best stock to be used for the war effort. They were shipped to Iceland to be used by the Norwegian Army. The dogs did not return and it wasn't until 1952 that word came from Leonhard Seppala that the Norwegians took the teams to Svalbard where they performed very well. In the fall of that same year, 1942, the British government once again approached the Clarks’ for dogs, only this time requesting forty. But after the twenty-four that were shipped out the previous summer, there were only about eight to ten that could be spared. Mr. Clark bought some dogs back from Felix Leser. The balance of the order came from "The Pass" [The Pas], Manitoba. The representative of the British Army had gone there looking for stock but eventually decided to send the sixteen year old Murray Clark back there to seek out and purchase "able bodied sled dogs or dogs with Eskimo blood in them to add to what we could supply to put together forty dogs - three teams." Within a few days of his return to New Hampshire with those dogs, all forty, along with all the sleds, harnesses, cold weather clothing, veterinary supplies frozen horsemeat, two Canadian soldiers who had been staying in New Hampshire to assist with the transfer and to learn how to manage the dogs, and Murray Clark, were taken by tractor trailer and the Clark's truck to New York City where the shipment was loaded onto a ship. "It was sixteen days at sea from New York harbor to Liverpool, England in some of the worst God forsaken north Atlantic winter weather. I stayed over in Scotland about six weeks training Royal Scottish Fusiliers how to handle and operate the teams of sled dogs. I was a 16 year old civilian boy working under secret orders of his majesty. They led me to believe that small groups of the dogs were going to be sent on commando missions to knock out German radio stations on the mountains adjacent to Norwegian fjords. But the dogs I delivered to Scotland never left the United Kingdom. They were disposed of in the very place where I delivered them. They were never used."

One of the "Browns" demonstrates the shaggy coat.

Text on photo reads,

"Big Daddy's Boy, Eskimo Sled Dog

Ed Clark's Ranch, North Woodstock, NH"

Shortly before Murray Clark ended his verbal journey back in time, we got to ask a couple of questions.

Q: Did you think of the dogs as household pets. When you were selling puppies, what were your criteria for owners?

A: "My father would always say they were a man's dog. They're an outdoor dog. They have a big appetite. They're happy, they're friendly but they're really not a quiet pet type dog for the household. We rarely had one of the dogs inside unless it was ill or wounded or needed some special attention or we were calling the pups to the doorstep to feed them oatmeal and milk to help out the mother. We also supplemented them with cod liver oil to bring those pups along."

Q: How big were your dogs?

A: "The average male would have probably been in the neighborhood of 70-75 pounds, an exception would have been around 80 pounds. We may have had a male who weighed as much as 100 pounds. The females would have been 45 to 60 pounds and about 21 inches in height."

Q: What about their health? Did you happen to recognize anything that might have been of an inherited nature that was a problem?

A: "I would say that having lived so many hundreds of years as a breed hardened to the weather, but being isolated in the north, they had no natural resistance to some of the common diseases that go around, like distemper. I have seen practically all our dogs wiped out because my father would not inoculate them in advance. We always wormed them. I can't recall seeing any physical deformities or inherited problems. We could tell if perhaps there was some strange blood in a litter of puppies if they became lop eared. That was immediately a sign of impurity. We wanted only pure dogs but we found ourselves on occasion raising and feeding half breeds which we sold or gave away or whatever, or my father might destroy the pups, if the mother was bred by a stray dog."

Q: You had several different populations of dogs from different locations. Do you remember when the last group of dogs coming from the north would have arrived?

A: "In about 1944 or 1945, my mother and brother went to Presque Isle, Maine to get some US Army dogs that I guess had come down from Thule, Greenland. I can't remember too much about them except they were said to be from the far north and isolated."

* * *

The Clark Trading Post, a large complex of buildings located on the well traveled Route 3 in Lincoln, New Hampshire, U.S.A. is a well known tourist destination. The featured attraction is the performing black bear exhibit. Arriving at the Trading Post in 1931, nine years after the appearance of the first dogs, the bears, unlike the dogs, had proven to be more profitable. The last "Eskimo" dog disappeared from the establishment in 1973. The dog era at the Ranch/Trading Post is remembered by a large exhibit of photos, trophies, newspaper items, various equipment in the Trading Post's well appointed Museum.