Table of Contents

*

Featured Inuit Dog Owner: Merv Ehrich

*

Jubilee Medal Awarded to ISDI Co-Founder

*

Blue Eyes in Norwegian Greenland Dogs

*

ISD Enthusiasts Speak out on Blues Eyes

*

ISDI's Official Stand on Blue Eyes

*

Mountie, Alouette and Moose

*

Following Nanuk's Tracks

*

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part 1

*

News Briefs:

New ISDI Scandinavia Web Site

Atanarjuat Update

Dog Teams in Iqaluit

Grammar Lesson

ISDs in Museum Exhibit

*

Poem: Lost Travellers

*

Book Review: first Nations.... first Dogs

*

ISD Enthusiast's First Novel Published

*

IMHO: Seeking to Answer the Wrong Question

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

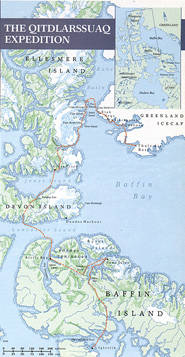

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part I

by Renee Wissink

On my knees at the edge of the crevasse, calling into the darkness below, I felt the exhaustion of a long, difficult day overtake me. A ground blizzard was blowing up, and it now appeared that Commander Peary was dead, mortally slammed into one of the jagged ice walls or slipped from his harness and caromed like a rag doll from ledge to ledge into the depths of the glacier. I was tired, terrified and incredibly frustrated. Greenland, our goal, had been visible most of the day, lying a scant 30 miles (48 km) across Smith Sound, and yet those miles might as well have been the 1,700 (2,700 km) we had already come. Since morning we had struggled 18 hours but had covered less than two miles (3 km). The open waters of the sound had cut off our sea route and forced us to take a desperate, potentially disastrous detour - Ellesmere Island's heavily crevassed Alfred Newton Glacier. For the first time, defeat was a distinct possibility.

Despite my fatigue, I was delighted to feel a lively heft at the end of the 50-foot (l5 m) rope that connected Commander Peary, my lead dog to the sled he had been helping to pull. Both of us were equally grateful as I hauled the dog up over the lip of the crevasse. Gently checking him for injuries, I realized I could no longer remember how many times one or another of our dogs had broken through the windblown snow that bridged the glacial fissures. I knew, though, that it was happening too often. Dogs, as long as they did not slip out of harness, were relatively easy to extricate from a crevasse, but rescuing an unroped teammate or one of our 750-pound (340 kg) Inuit sleds would be quite another matter.

As leader of an expedition intent on recreating the journey of a remarkable 19th century Inuit shaman named Qitdlarssuaq (kit-LAR-soo ak), I could not justify loss of life. But thoughts of defeat were equally troubling. The spring breakup was too far advanced for us to retreat along our outward route, and the expedition's remaining cash - $88 - definitely precluded air support. I wished that I, like Qitdlarssuaq, could go into a trance and send my spirit on a reconnaissance flight of the terrain ahead. Instead, I stumbled to my feet and called for a sled-side conference with my four companions. We would camp, I said, until visibility improved. After that, we would proceed with two roped skiers leading the way.

Strategy

planning

Courtesy

Nunavut Tourism

The blizzard lasted nearly a day, and I spent many hours thinking of Qitdlarssuaq and questioning my wisdom in trying to trace his footsteps. In the early 1830s, Qitdlarssuaq and a band of some 50 followers travelled north from their home territory on central Baffin Island. Thirty years later, they showed up in Greenland, where they joined that country's Polar Eskimos. Even for the highly nomadic Inuit, the journey was one to the back of beyond. Their accomplishment, in anything resembling modern times, was unique: Knud Rasmussen, the famous Greenlandic explorer and ethnologist, said it was "the only example we met among the Eskimos of a group having undertaken a tribal migration implying a journey over several years, from one polar region to another, using their own methods and with no influence from civilization."

If the journey was unique, however, it was also partially inadvertent. On a caribou hunt near Cumberland Sound in 1832, Qitdlarssuaq was enlisted by a hunting companion named Oqe to kill yet another companion, Ikieraping. Oqe, who at an earlier date had fatally harpooned Ikieraping's brother, had been told in a dream that Ikieraping was about to avenge the death. Oqe awoke knowing that he must avenge the avenger. It was Qitdlarssuaq, however, who took up the boulder and crushed Ikieraping's skull. The oral tradition that has immortalized Qitdlarssuaq is vague about why he became directly involved in the murder, but there is no doubt that in so doing, he put himself in the same unenviable position as Oqe. In the Inuit culture, a murder could be revenged by a man's male relatives, even many years after the act, and Qitdlarssuaq's life became a constant glance over the shoulder. Understandably, he soon began to think of more peaceful places, and one day, he and Oqe gathered their respective families and headed north. It was the first stage in what was to become the shaman's epic journey.

Given the circumstances, Qitdlarssuaq's departure was almost to be expected. That he left with a retinue of 50, however, is a noteworthy achievement and one that can be attributed to his unusual powers of leadership. Pre-Christian Inuit life was anchored by a strong belief in spirits; evil spirits brought hunger, sickness and death; helping spirits brought insight, bravery, good fortune and success. The spirits, though, were generally inaccessible to most Inuit, and it was just a select few - those possessed of a secret language and the power to send their souls on flights to other realms who could fully confer with the spirits and plead the case of their people. Those few, the shamans, were both revered and feared; indeed, the only other Inuit who commanded collective respect were the camp leaders, usually elders, who dictated the rhythms of the yearly cycle. Although most groups had a separate leader and shaman, Qitdlarssuaq appears to have been both.

Even as a young man, Qitdlarssuaq evidently had great personal power; by the time he died, in 1875, he was legendary. Once, for instance, while out hunting polar bears far from land, Qitdlarssuaq and a young companion were caught in a severe storm. The sea ice was shattered, and the open sea raged around them. Qitdlarssuaq ordered the young man to lie face down on the sled and to keep his eyes shut. Soon, however, the young man felt the sled begin to move, and being both frightened and curious, he opened one eye and saw that Qitdlarssuaq had turned himself into a polar bear and that his own dogs were chasing him. Wherever the bear trod, the sea turned to ice. He also saw, to his horror, that the runner on the same side of the sled as his open eye was sinking into the sea. He quickly closed his eye again and did not reopen it until the sled stopped and Qitdlarssuaq ordered him to rise. The shaman was again a man, and they were safely on land.

It was little wonder, then, that when Qitdlarssuaq decided to leave, many of his people were ready to go with him. In time, he was to seem to them immortal, an Inuit superman. When he travelled at night, they said, a luminescent glow emanated from his head.

My own interest in Qitdlarssuaq was sparked in 1985. Seven years in the north as a teacher, wildlife technician and wilderness guide had made me painfully aware that while any number of other countries put great stock in the Arctic and its people, Canada itself seemed to take the north for granted. I began to dream of a distinctly Canadian journey, one that would be novel, with historical importance, a human element, spectacular scenery and abundant wildlife. When I shared my thoughts with John MacDonald, director of the Eastern Arctic Scientific Resource Centre in Igloolik, his response was almost immediate: "Look into the Qitdlarssuaq story."

MacDonald directed me to Father Guy Mary-Rousseliere of Pond Inlet, an Arctic scholar who has devoted years to collecting and recording the oral tradition that surrounds Qitdlarssuaq, and with the aid of his manuscripts, my dreams began to take shape. Qitdlarssuaq spent the first 20-odd years of his exile roaming the eastern coast and northern reaches of Baffin Island, and it was not until after 1850, following a pitched battle with some of Ikieraping's relatives who had tracked him down, that he left the island and began to move north with any real determination.

Crescent shaped toggles attach harness

to tug line

Courtesy Nunavut Tourism

Accordingly, I decided we would start our own trip from my home in Igloolik, travel to Pond Inlet and, from there, approximate Qitdlarssuaq's journey north, following a route drawn from the Inuit stories, corroborating archaeological sites and various European records of contact. Thus we would traverse Borden Peninsula, cross Lancaster Sound, bisect Devon Island, cross Jones Sound and work our way up the east coast of Ellesmere Island until we found good ice on Smith Sound and thence cross to Greenland. Including all the zig zags, we would travel 1,800 miles (3,000 km) and take three months to do it.

Preparations began in July 1986 for a mid-March 1987 departure. I had no financing and no team, but I dove headlong into the project - which, I soon learned, was about as pleasurable as diving into ice-filled Arctic waters. By Christmas Day, I had raised only $5,000 of the estimated $75,000 cost, had almost everything I owned up for sale and was spending much of my time swearing at Canadian indifference to what I was sure anywhere else would be enthusiastically received proposal.

The team, at least, came together smoothly. I wanted the expedition to be not only Canadian but predominantly northern and preferably half Inuit. It took almost no time to convince Paul Apak, an Inuit Broadcasting Corporation cameraman, and Theo Ikummaq, a former renewable resources officer, to sign on. They were acquaintances from Igloolik, and I knew them to be good dog handlers who shared my zeal for travel on the land. It came as a total surprise, however, to learn that both were directly descended from Qitdlarssuaq's sister, who had been a powerful shaman in her own right. Next to join was Mike Beedell, an Ottawa-based adventurer and photographer who had spent several summers travelling the Arctic. He had no experience with dogs, but I knew he would quickly adapt. Our last and youngest member was Mike Immaroitok, a nephew of Ikummaq's who, like so many young Inuit in small communities, was unemployed and facing a bleak future. We all agreed that the expedition would be a valuable experience for him.

March came around all too quickly, and the stress of final outfitting bore down heavily. With two days to go, I had yet to receive approval from the Canadian Armed Forces for my request for an airlift home from the American military base at Thule, Greenland, and there were scores of last minute details to attend to. As much as was feasible, we wanted our travel to be traditional. Our 46 dogs, for instance, divided into three teams, were purebred 70-pound (30 kg) Eskimo sled dogs, decedents of those the Thule people had brought with them from Siberia 1,000 years ago, and their traces and harnesses were fashioned from bearded sealskin. The sleds - 17 (5 m), 18 (5.5 m) and 20 feet (6 m) long - were the overall shape, size and design of the traditional qamutiik although we built them of wood, rather than bone and antler. We also had sets of untanned caribou trousers, parkas and boots, which we discovered to be vastly warmer than any high-tech synthetics on the market today. Their sole drawback was that they shed horribly, and by the third or fourth day out, we graphically understood why old Arctic hands say you cannot consider yourself a true northerner until you have consumed your weight in caribou hair. Week after week, we inhaled it, ate it and plucked it from our eyes and ears and underwear.

We planned to build igloos when conditions were favourable, and we did carry some char, seal, caribou and ripened walrus meat (the latter being an acquired taste) with us, but time limitations and hunting regulations demanded that we also pack tents and both freeze-dried and boil-in-a-pouch food. We mixed and matched caribou skins and polar bear skins with fibre-filled sleeping bags and granted a flat-out concession to the 20th century by hauling along a radio telephone and cassette tape recorders.

The journey

begins

Courtesy

Nunavut Tourism

On March 8, we awoke to a clear ice-spangled morning of minus 40 degrees, cold but suitable for travel. Most of Igloolik turned out to help us lash the loads onto the sleds and harness the dogs. The bad jokes and well-wishing lent a carnival-like atmosphere to the proceedings, and the dogs, like a psyched-up gang of renegade bikers, were cacophonous in their eagerness to begin. Finally, there was nothing left to do but step on the sled and yell at Beedell to release the anchor chain. The dogs needed no urging: the sled shot forward through the pack ice with Beedell sprinting in hot pursuit. A final lunging leap on his part, and we were off and running.

In fact, our leave-taking was less than Hollywood-perfect. At the last possible moment, Commander Peary seemed to have second thoughts about going with us and thus began the trip variously upside down, under, over, about and behind the other dogs, who entertained no such doubts. Further team trouble developed a half mile from the village when some quibble over which dog was doing what led to an all-out battle. Once that was decided, though, they settled down and began to work. The brilliant sea ice of Fury and Hecla Strait stretched before us, and only the Styrofoam-like squeaking of the snow and the panting of the dogs broke the heavy northern silence.

The reality of the expedition hit home the second day with a ground blizzard that reduced visibility to about 50 feet (15 m). We navigated in the traditional manner, with the aid of wind direction and the pattern of the snowdrifts, but even the experienced of Apak and Ikummaq could not keep the three teams together. Several times during the day, we became separated, and each time, the dogs pulled us back together, suddenly veering off a given course to find each other in the blowing snow. Because ground blizzards are simply strong winds that carry surface snow, we could occasionally get our bearings by stopping the dogs and standing on top of the sleds, which would put our shoulders and heads above the storm. Still, it was exhausting, disorienting work, and at the end of the day, when we were settled into our second camp, Apak looked up from his cup of tea and spoke the obvious truth: "Boys, it's a long way to Greenland."

Into a

blizzard

Corel

photo