In this Post

From the Editor

The Evolutionary History of Dogs in the Americas

Film Review: Angry Inuk

Free Northern Periodicals Online

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor's/Publisher's

Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch Website and

Publications of the Inuit Sled Dog– the

quarterly Journal (retired

in 2018) and PostScript – are dedicated to the aboriginal

landrace traditional Inuit Sled Dog as well as

related Inuit culture and traditions.

PostScript is

published intermittently as

material becomes available. Online access is

free at: https://thefanhitch.org.

PostScript welcomes your

letters, stories, comments and suggestions.

The editorial staff reserves the right to

edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

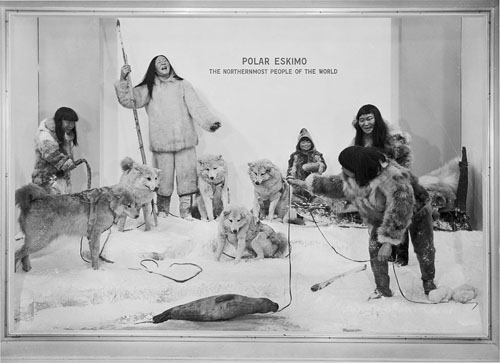

From the National Museum of Natural History, a 1957 anthropology diorama of a life group from

the arctic region entitled "Polar Eskimo, the Northernmost People of the World." It formed part of

the "Native Peoples of the Americas" exhibit.

Image:From the Historic Images Collection of the Smithsonian Institution Archives .

The Evolutionary History of Dogs in the Americas

Appearing in the July 6, 2018 issue of Science, this recently published research has implications for the archaeologic and genetic history of the Inuit Sled Dog. Like a bolt of lightening over a western forest on a dry day, this news caught on fire with lots of mainstream media outlets. I see this sort of like the game of telephone where the initial story gets told over and over again with perhaps a different skew, interpreted, perhaps, by folks who do not necessarily possess a skilled understanding in the field of evolutionary biology. Well, neither do I, and that’s why I contacted corresponding authors for an original copy of the paper, did my best to read it (several times) and then ask questions. I am grateful to Dr. Greger Larson, who was kind and patient enough to respond.

Copyright rules do not permit me to include here the original paper, but here is a link to what is publically available which includes the list of co-authors, including the corresponding authors.

But wait, there’s more! Also in this issue (volume 361) of Science is “America’s lost dogs”. Again, because of copyright rules, only an article summary is publically available here. This is an overview of “The Evolutionary History of Dogs in the Americas” and is easier for non-scientists to understand and I venture to suggest that the authors are in a better position to give this overview than some of the mainstream media’s interpretations. “America’s lost dogs” includes the email for the corresponding author, if you want a complete copy.

Below is a dialogue I initiated on July 5th with Dr. Larson. Again, I am grateful to him for his enlightenment.

TFH: Would you consider precontact populations of dogs to be domesticated?

GL: Yes, by definition all dogs are (or descend from) domestic populations.

TFH: Please forgive me. I have read and re-read this sentence at least a dozen times and I am totally hung up on the ”all dogs are...(or descend from) domestic populations.” I read this as all dogs descend from domestic populations. No wild progenitors? How could that be?

GL: I’m saying that dogs only emerge through a close interaction with people. Rather, without people there are no dogs. Just wolves. Sometimes dogs can be introduced to a new place with people and then go feral (dingoes), in which case they can’t really be classified as ‘domestic’, but they descend from a domestic population that only arose via a relationship with people. Therefore it is impossible for dogs to have been in North America prior to the arrival of humans.

TFH: Would you consider precontact populations of dogs to be described as aboriginal landraces?

GL: If you like. I wouldn’t call them ‘breeds’ per se since that’s a Victorian construct, but they were dogs.

TFH: This is an excellent point, one that I have emphasized when trying to explain the demise of aboriginal and real working dogs during the Victorian era of developing dogs for show and pets. And it begs my question of when does a (real working) or aboriginal landrace lose its original genetic identity and potential, and become a cultured breed of a different kind.

GL: It’s a continuum and the definitions are arbitrary, but the distinctions can be interesting in terms of what they reveal about the changing relationships between people and dogs.

TFH: “..following the arrival of European dogs after colonization…” When and where do you define European colonization? I am specifically interested in the Canadian Arctic and Greenland. Long before “colonization”, non-native populations were in these areas on various exploration missions.

GL: For the purpose of the paper we’re sticking with convention and going with post-Columbian.

TFH: “Introduction of Eurasian Arctic Dogs (e.g. Siberian Huskies) during the Alaska gold rush..” The arrival of pre-Siberian Huskies, known as Chuckchi dogs pre-dates the gold rush era. What the gold rush era signifies in terms of the arrival to that geographic region is the “import” of non-indigenous European origin dogs brought by gold seekers. (Think of the dogs in Jack London stories.) Many, but not exclusively were European mastiff types, as identified by historic photographs. Some were Icelandic dogs.

GL: We agree.

TFH: “…some modern American dogs retain a degree of ancestry from precontact populations…” How do you define “a degree of ancestry”? Are these not in some, but not all cases, legitimate uncontaminated landraces, such as the Canadian Inuit Sled Dog?

GL: There are lots of complicated things going on in the North. If you look at the tree we’ve focused on the identification of the PCD clade which is closely related, but different from the clade of Arctic dogs which have their own story, and one we’re following up in a study we’re working on right now.

TFH: Wow! This is exciting, and work I eagerly look forward to reading about. One thing that concerns me greatly is the source of the material you will be examining, specifically from live dogs. Dmitry Belyayev’s classic work with foxes demonstrated the stunning phenotype and behavior changes resulting from breeding solely based on reduced flight distance to humans. There is no doubt (as has been shown time and time again since the Victorian England era the drastic changes when dogs are not bred primarily based on working functionality) that purebred/cultured polar spitz breeds have changed in appearance and behavior as well as loss of intrinsic aboriginal working/survival skills. The landrace Eskimo Dog of the early 1900s was in short order turned into the cultured and thoroughly diminished Alaskan Malamute breed. I am concerned how examining DNA kennel club registered show/pet dogs can be substituted for the more enlightening DNA from aboriginal landrace dogs. It is great that you are aware of Dr. Morton Meldgaard’s QIMMEQ project. At least when those aboriginal Greenland Dogs are examined, they genetically represent the dogs of Canada as well. Will your project seek to obtain DNA from dogs much closer to their aboriginal ancestry?

GL: We have mostly ancient remains but I think we may now be collaborating with a different group and they have sampled modern populations.

TFH: “..archaeological dog remains collected in North America…” At what latitude were these collected? Were they representative of dogs, originally called Eskimo Dogs, now known collectively as the Inuit Sled Dog, the landrace which includes both the Canadian Inuit Sled Dog and the Greenland Dog? Both have been determined by morphometric and genetic analysis to be the same landrace .

GL: You can see the map that shows the location of the ancient dogs we analyzed. And see my answer above.

TFH: Where do you separate from each other “modern and ancient canids”?

GL: For our purposes ‘ancient’ simply means archaeological remains. Modern means recent dogs that were sampled when they were alive.

TFH: Why has no mention been made of the Canadian Inuit Sled Dog?

GL: We did not have any samples of this dog and we are working on a paper about Thule and Arctic dogs now.

TFH: Why has any mention been made of the Alaskan Malamute, which did not exist prior to 1935 American Kennel Club registration? The progenitor of the Alaskan Malamute was the (then called) Eskimo dog of the Kotzebue Sound region of Alaska and also Labrador! Did you examine DNA from Alaskan Malamutes, which is not ancient (as some biologists have reported), not a landrace, but as a cultured/man-made breed?

GL: We are aware of this issue (see Larson, et al. Proceedings of the Natl. Academy of Sciences 2012). The Malamute DNA was published by other authors and we simply made use of that data here to show how it’s related to all the dogs we sequenced.

TFH: Alaskan Huskies, a cross-breed, are the very definition of the subject of the blind men and the elephant! While early on they may have represented entirely polar phenotype dogs (such as the Alaskan bush dogs), since the early 1900s they have been deliberately mixed up with non-polar phenotype dogs such as pointers and hounds (of European origin) in order to excel as racing dogs. Why are they grouped in the same mention with Alaskan Malamutes and Greenland Dogs?

GL: Because their genomes cluster together on the tree.

TFH: Could you please summarize the rest of the article.

GL: Our analysis demonstrated that there is very little if any genetic legacy of the dogs that were present in the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans, in the dog population that is now present throughout the Americas.