From the Editor

Astrup’s Harness

Akunnirmiut Nunavut Quest, Pt. 2

Sleds, Dogs and Nitrate Film

In the News

Fan Mail

CAAT 2012 Baker Lake Animal Wellness Clinic

Book Review: Kamik, an Inuit Puppy Story

Movie Review: Inuk

IMHO: Henson, Pt. 2

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Astrup’s original seal skin harness from 1895 Photo: J.W. Moe

Astrup’s

Harness

A personal voyage to understand an old sealskin sled dog harness

by Jonas Warme Moe

Lorenskog, Norway

A personal voyage to understand an old sealskin sled dog harness

by Jonas Warme Moe

Lorenskog, Norway

Historical background

Eivind Astrup (1871-1895) could easily have become one of the pillars of Norwegian polar history - if not to say the polar history of the world. At nineteen years-old, he joined (with very poor English skills) Robert Peary’s two expeditions to North Greenland, and it was primarily his meticulous observations and documentation that finally established Greenland as an island and not part of an Arctic continent as many had believed. In his lifetime, Astrup became as popular, if not more popular than Fritjof Nansen himself. For Roald Amundsen, Astrup was the great ideal of a successful polar explorer.

Astrup crafted sleds for the Peary expedition - copied from the nearby Inuit families - and taught Peary and the other explorers how to ski. His only book, With Peary Near the Pole, reveals a deep respect and understanding of the local Inuit culture. He was the first to combine dog sleds with skis - and thus laid the ground for the future success of both Nansen and Amundsen.

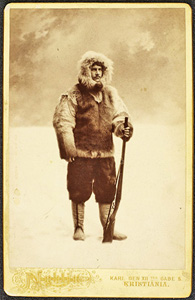

Eivind Astrup, ca 1893

Photo: Daniel Georg Nyblin (1826-1910);

courtesy of the National Library of Norway

Once returned to Norway, Astrup planned great expeditions, combining native equipment such as sleds and reindeer clothing with modern tools like hot air balloons to conquer the poles. However, he was infected with typhoid fever, almost certainly obtained by eating rotten pemmican during the second Peary expedition, and became very ill. During Christmas weekend of 1895, he went for a ski trip in the mountains and never returned.

Although some newspapers soon speculated suicide, Astrup’s death was covered up for many years. It was said that he fell and slipped on some ice and cracked his head on a rock. However, rumors of a gunshot soon grew in a nearby village, and that a fired gun had been taken from the death scene. Today Astrup’s suicide is a fact, though the reasons are not fully understood. Rumors of an affair with Eva Nansen, Fridtjof Nansen’s wife, still exist but are highly doubtful and not documented anywhere. To me, it is more likely that he could not cope with the fact that he was ill and never would be well enough to achieve his goals as a polar explorer.

From his second expedition, Eivind brought back to Norway with him four Greenland Dogs. These were the first in Norway and he raised them on a small island in the Oslo Fjord. When the dogs were old enough he trained them on the iced sea outside Oslo. The ash sledge they pulled was his own native-inspired design and built by experienced Norwegian sledge carpenters. However, before the season was over he had sold his beloved dogs. The dark thoughts that soon were to cloud his mind were already on the horizon.

After his death Astrup’s siblings donated his sledge and the sealskin harnesses to the Norwegian Ski Museum. There they would lie untouched for over a hundred years.

Recreating history

My interest in Astrup’s harness came from an unlikely angle. Being neither a musher nor owning a polar dog, why this interest in reconstructing old polar equipment?

A screenplay I was working on was suddenly canceled and years of work were basically wasted. I needed to do something positive so I decided to fulfill an old dream of mine, which was to reconstruct Roald Amundsen’s dog harnesses from his legendary South Pole expedition. I contacted my great-uncle at the Skimuseum in Oslo and got a positive response. I was very surprised when I arrived at the museum and saw what he had found for me. It was not Amunden’s harness, but an even older one - Eivind Astrup’s. From the first time I held it, I knew I had found something special. The shape and very effective design seemed so modern. I went home, ready to get to work.

Two of my reconstructed harnesses.

These are made of cowhide, not sealskin.

Photo: J.W. Moe

The Harness

Having been stored away since Astrup’s death in 1895, the leather was very dry and had big cracks in it. My first task was to grease it up, hoping to make the leather so flexible that I could stretch it out again. This process took days of using my fingers to carefully apply leather grease into the old, hard leather. During this procedure, I found myself very lucky to be able to work with such an old artifact from our Norwegian sled dog history. Astrup was, after all, the one who brought dog sledding to Norway! After this process was done, I started to photograph the harness in detail and take careful measurements of all the different parts. I was very impressed with the simplicity of the design. It is cut from one long piece of leather and not sewn with sinew (as many other Inuit harnesses) but tied together with two leather straps. It does not have a quick release nor a leather tug line, but is fastened to a hemp rope six meters (6.6 yards) long with a possibly hand forged iron snap clip on the end.

A very strange harness indeed. One would think that Astrup bought harnesses on Greenland with the dogs. But then again, why these seemingly modern adaptations to the harness? Knowing that Astrup made all the skis and sledges for the two Peary Greenland expeditions, one might be tempted to think that Eivind made the harnesses and tug lines himself, or at least modified already existing harnesses to fit his needs. The leather is most possibly from ringed seal, making the puzzle even stranger. Question 1: If the harness was Inuit made, why would hemp rope have been used? Question 2: If Astrup made the harness, why would he have substituted hemp rope and a quick release snap clip for the proven-to-work Inuit materials of a seal skin tug line and an ivory (or bone) toggle?

Norwegian Greenland dog, Laila, the first dog to wear an Astrup harness

in over a hundred years! Photo: J.W. Moe

Hoping to find an answer I realized that I had to understand more about Inuit Dogs and Inuit culture. This soon lead me to The Fan Hitch website and journal. Many months - a lot of incredibly valuable email contact with Sue Hamilton - and a lot of requests to museums in Alaska, Canada and Greenland. I am more knowledgeable about Inuit Dogs and old dog harnesses, but not really any closer to a definite truth about the museum harness. Who made it?

The mix of old knowledge and “modern equipment” is not unique to Astrup’s harness. Both Nansen and Amundsen and many of their contemporaries based their equipment on native designs. They understood and appreciated that these people had lived in this polar environment for thousands of years and knew very well what worked or not. So maybe, just maybe, Astrup did what Inuit would do. Once he returned to Norway, he adapted to the terrain, circumstances and resources available. Maybe some of the leather tug lines broke and he simply replaced them with what he had. On the fjord outside Oslo there would be no need for a quick release from the harness because of polar bears or other natural enemies. And the iron snap clip would probably be as efficient, if not better than ivory toggles anyway.

Testing the harness

Some tension against the harness to show fit.

Photo: J.W. Moe

One of the main goals in actually making real and working leather reconstructions of the harness was to find out how well the harness might have performed on the dogs. This is of course very much linked to my respect and interest for native knowledge and tools and my hobby of leatherwork. From this a new set of questions arises: If well fitted, how well will the harness work on modern dogs and how does it compare to a modern nylon harness? That is my next project. I’ll keep you posted.

Author’s Notes:

Astrup’s harness was kindly borrowed from the Norwegian Ski Museum.

The dog model is the beautiful Laila of Tinka’s Kennel, Norway. A deep thank you goes to Laila’s owner, Katinka Mossin for her time and knowledge.

A blog about the harness is currently under construction. In the meantime, any inquiries about the harness can be sent to jonas.w.moe@me.com.

Jonas Warme Moe is a freelance screenwriter and sled dog enthusiast, currently researching and writing a book about mushing history in Norway.