From the Editor: On the Radar

Citizen Scientist Participation Requested

On the Trail of the Far Fur Country

Dealing with a Runaway or Breakaway Team of Inuit Dogs

The Chinook Project Returns to Labrador

Website Explores Indigenous People of the Russian Arctic

Book Review: Harnessed to the Pole: Sledge Dogs in Service to American Explorers of the Arctic, 1853-1909

IMHO: What’s Enough?

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Harnessed to the Pole:

Sledge Dogs in Service to American Explorers of the Arctic, 1853-1909

by Sheila Nickerson

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

The next time I see the words: “Inuit Dogs have played an important role in Arctic exploration”, Sheila Nickerson’s book, Harnessed to the Pole; Sledge Dogs in Service to American Explorers of the Arctic, 1853-1909, will haunt me. For letting it go at just those ten words is a trivialization, a glossing over of what actually happened to those hundreds upon hundreds of dogs during their use. Nickerson’s accounts gleaned from expeditionary books, field notes, research papers, museum documents (she includes ten pages of chapter notes and a four-and-a-half page bibliography) offer details of the travels of Elisha Kent Kane, Isaac I. Hayes, Charles Francis Hall, Frederick Schwatka, George Washington DeLong, Adolphus Washington Greely, Frederick A. Cook and Robert E. Peary. (To her credit, in writing her book Nickerson recognizes and acknowledges how writers of the era put their own slant on the relationships and uses of the dogs.)

Most chapters are titled bearing the names of dogs whose activities were of particular note to the explorers who used them. There was also story after story of starvation: humans eating dogs, dogs eating dogs and puppies, puppies eating puppies, dogs eating dish rags, wooden crates, ammunition, research notebooks; and dangerous encounters with bears, musk ox and wolves. But Nickerson also covers topics such as “Disease and Diet” (the ruthless working conditions made worse by sickness, much of which was the result of poor quality rations, including salted meat and pemmican with raisins and currents – now known to be nephrotoxic to dogs), “Dogs and Driver: The Essential Team”, “Dogs as Showmen” (having survived the Arctic only to be brought to the United States and made into P.T. Barnum circus attractions), plus general descriptions, dog behavior and social order, their hunting prowess, their aboriginal keeping and use, the importation of non-indigenous dogs into the Canadian and Greenland north, and much more.

The dogs were generally held in awe for their stamina in the face of adversity:

“…Averaging eight days between feeds…the powers of endurance of these brutes seems absolutely beyond comprehension. They bear up under this terrible strain of fasting with a fortitude that would bring compassion from the heart of a hickory tree.”

Schwatka, page 174-175

“The instinct of a sledge dog makes him perfectly aware of unsafe ice, and I know of nothing more subduing to a man than the warnings of an unseen peril conveyed by the instinctive fears of the lower animals.”

Kane, page 41

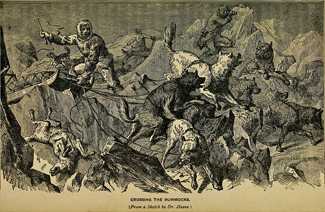

“Crossing the hummocks” from The Open Polar Sea, p. 322,

by Isaac I. Hayes sketched by him during his voyage of discovery

towards the North Pole, 1860-1861

However, while occasionally appreciated for their mere presence as companionship, the dogs were often vilified for their survival activities, and willingly dispatched for utilitarian reasons as food sources – out of desperation as well as heartless calculation of expedition goals,

“For Cook, the number of dogs to be eaten – twenty – was part of the formula he calculated for success.”as well as expediency,

Nickerson, page 248

“…what are we to do with the faithful dog survivors [when we head home]? ..We must part…Our sleeping bags and old winter clothing were given as food to the dogs…The [eight abandoned dogs] howled like crying children. We still heard them when five miles off shore.”At the hand of explorers and with the ‘help’ of Nature, these poor dogs were, for a large part, brutally treated. Early explorers, while recognizing their importance, saw and employed them first and foremost as commodities, means to an end, nothing like millennia of symbiotic survival relationship in an aboriginal way of life, but all about the unremitting search of ego gratification, greed and quests for honor and glory, in the name of god, rulers and countries.

Cook, page 250

“…but when we leave here – if in boats, as probable – the dogs will be shot, or perhaps left with a few days food against the possible event of our return…[Barring our return], they would starve to death.”

Greely, page 240

Fascinating details of polar history with a very strong focus on the dogs, Harnessed to the Pole; Sledge Dogs in Service to American Explorers of the Arctic, 1853-1909 is not for the faint of heart, but is a book that needed to be written as Nickerson puts it, “…to pick up [the dogs’] trail before it is swept away and to follow as best we can before it is lost in darkness and distance.” And it ought to be read so that “Inuit Dogs have played an important role in Arctic exploration,” is wholly understood and appreciated, not merely seen as ten words on a page.

Harnessed to the Pole: Sledge Dogs in Service to American Explorers of the Arctic, 1853-1909 by Sheila Nickerson; published in 2014 by the University of Alaska Press; ISBN 978-60223-5; 6” x 9” paperback; includes 60 fantastic halftones of archival drawings and very early photographs plus 15 historical maps; available from the publisher for $24.95 USD; also at bookstores and online retailers.