Table of Contents

*

The Return

*

Dogs in Greenland

*

The Contribution of Dogs to Exploration in Antarctica

*

Page from the Behaviour Notebook: Raising Raven

*

Antarctic Sketches

*

Physiology of Sledge Dogs

*

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part 2

*

News Briefs:

Thesis update

Blue Eye update

Mailbag

*

Product Review: DirectStop®

*

Book Review: Carved from the Land

*

Tip for the Trail: Re-lining Water Jug Caps

*

IMHO: Preservation vs. Saving

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

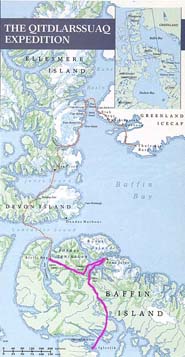

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part 2

by Renee Wissink

Our route took us first north from Igloolik toward Pond Inlet, and although the intervening topography, largely featureless, should have been pleasant travelling, we found ourselves in a constant struggle with the cold. The temperature never rose above minus 31 degrees F (-35°C) and, accompanied by strong winds, was often much colder. The conditions turned the snow into granular concrete, and unless we kept our runners well iced - a time-consuming, tedious task - the sleds would drag badly, slowing the pace of the dogs and wearing the patience of the drivers. Beedell, as my sled mate, kept me posted as to the various hues my face took on, and we both froze our cheeks and noses repeatedly, all the while envying our Inuit companions, whose small noses seemed immune to the cold. Our facial hair was another problem; our beards were often so ice-coated that we could not find our mouths, let alone feed ourselves. In camp, we found it took equal parts of cursing and coaxing to light the stoves, erect the tents and otherwise fiddle the equipment that required manual dexterity.

Still, by the end of the first week, we were beginning to settle into a routine. Rising at 7, we would be finished breakfast, packed and have the dogs in harness by 9 or 10. The middle of the day was devoted to sledding interspersed with three or four stops either for tea or to re-ice the sled runners. On the good days, despite the cold, we would cover 40 to 50 miles (64-80 km). Setting up camp, preparing our second hot meal of the day and tending to the dogs took another two to four hours. If the snow were deep enough, and the right consistency, and if we were not too tired, we would build an igloo. Apak and Ikummaq were masters of the art, and I marveled at the ingenuity of the people who evolved such a simple, architecturally sound structure.

Building an

igloo

Corel

photo

Contrary to popular belief, igloos are extremely warm and wind-resistant - so tight, in fact, that we all received dangerous doses of carbon monoxide from our camp stove on the one night we forgot to provide adequate ventilation. Ironically, we were alerted to the situation by our shared fits of uncontrollable and incessant laughter. Beedell, who first realized the danger, suddenly grabbed a snow knife, sawed a hole in the wall and stuck his head in it, all the while hooting hysterically at the rest of us to do the same. It was a sobering realization, but Beedell said, "At least we would have died happy." For the next two days, beset by pounding headaches, we decided maybe that would have been a preferable ending to the incident.

Camp life was rarely dull. One morning I was awakened by Ikummaq's shouting, "Grab the skin clothes! Quick! The skin clothing!" The dogs, most of which roamed free at night, had broken through the igloo walls in search of food. Beedell leapt from his sleeping bag, screaming at the dogs as they hauled his caribou pants out the hole. He retrieved them seconds before they would have been torn to shreds by the ravenous pack. Although we carried enough food - usually frozen seal - for daily dog rations, the combination of hard work and extreme cold burned off the calories quickly. Anything even remotely edible had to be stored out of harm's way. Sealskin harnesses and traces, skin clothing and all the food had to be taken into the igloo at night or put atop a sled elevated on storage boxes. Even attending to bodily functions was hazardous: the rambunctious beasts considered the results of our morning "constitutionals" a delicacy, and we routinely carried ski poles with us to fend off overeager dogs when we went out.

After seven days, we had left the Arctic plain of northern Baffin Island behind and entered the rolling hills of the interior. Signs of caribou were frequent but disproportionate to the number of animals we actually saw. The one caribou shot by Apak the first week out was to be the last of the entire trip. Although our success did not depend on hunting, the kill provided some welcome extra meat. It also allowed Ikummaq to demonstrate some of the tricks he had learned from his years in outpost camps: a piece of his sled's shoeing had splintered off, and he wowed us by using the caribou's stomach contents as a kind of plastic wood to rebuild the runner. "Great stuff," he said, "Sticks like Krazy Glue."

Nunavut

Tourism photo

As we approached Milne Inlet, the topography change to the precipitous, deeply incised mountains that would dominate the remainder of the trip. The well-defined valleys and distinctively truncated peaks make it easier for us to find our way, since the swirling mountain winds meant an end to our snowdrift navigation. To double-check our position, we turned to a sun compass, similar to that used on aircraft, and to a radio direction finder.

The mountains along the inlet were made memorable not only because of their beauty but also because of they provided the setting for a major crisis with our dogs. During a midnight raid two days out of Pond Inlet, the dogs pilfered the last of their food for that part of the trip, and without fuel, they quickly weakened and began to falter. A slow walk was the best we could muster from them. Dog driving became just that: it took constant attention and some judicious use of our 30-foot (9 m) driving whips (which, during the early stages of the journey, proved to be as dangerous to myself and Beedell as to any of the dogs) to keep them moving.

Our final push into Pond Inlet was a 19-hour epic of frustration and fatigue, with me leading the dogs and Beedell pushing the sled. As night fell, we could see the lights of the settlement twinkling far across the frozen waters of Eclipse Sound, but they refused to grow any bigger or brighter as we struggled on. Beedell put his head down and his shoulder to the bar, resolving not to look up again until we reach our goal. He pushed and sweat and swore for what seemed like hours and when he finally dared to peek, the community looked more distant than he remembered its being when he started. I told him I thought we had wandered into some kind of Arctic purgatory, "where you have to push your dog team on an endless trail through the dark at 30 below."

Fifteen days out of Igloolik, we limped into Pond Inlet. Our arrival at 2 a.m. was even less graceful than our departure from Igloolik, but the community embraced us wholeheartedly and, the next day, treated us to a feast and dance. Apak, Ikummaq and Immaroitok were already being feted as heroes, and our trip had barely begun. Qitdlarssuaq would have had no such pleasant interlude - there were no communities per se in this time - but he did have the advantage of what amounted to a transportable settlement travelling with him.

We spent several days in Pond Inlet, feeding the dogs, repairing equipment and catching up on our sleep. We also met with a group of elders, all of whom had travelled extensively either as part of hunting parties or as guides with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police sovereignty patrols of the 1920s and 1930s. Their advice was invaluable. I was amazed for the rest of the trip by the accuracy of their predictions concerning weather and travel conditions. They were travelling men, the real Inuit: Inummariit.

The short leg of the journey from Pond Inlet to Arctic Bay I called the "Great Detour". Our ultimate goal, Qaanaaq, Greenland, lay northeast of Pond Inlet, but ice conditions in Lancaster Sound and the open water of Baffin Bay required us to travel west and sometimes even southwest. Inuit musk ok hunters in Pond Inlet had reported good ice in Lancaster Sound north of Admiralty Inlet, so we decided we would try crossing to Devon Island at that point.

Travel conditions suddenly became ideal. The days were growing longer at a rapid clip, and temperatures were up to about minus 13 degrees F (-25ºC). We spent our days sledding the sea ice of Eclipse Sound and Tremblay Sound in a continuous state of awe. One of the beauties of dog sledding is the long hours during which one can become lost within, pondering oneself or one's surroundings. As the various capes and islands slid past, we had copious amounts of time to wonder at their formation, what caused this shape or that, what forces raised and deformed their striations. The ice and the rocks took on shapes and personalities; a mermaid would slowly metamorphose into an elephant as we worked our way around it. The slow rocking movement of the sled, the creaking of the runners, the squeak of the snow beneath and the rhythmic movement of canine feet all added to the hypnotic effect. When the sled hit a large snowdrift or a quarrel broke out among the dogs or Beedell spoke to me, I often found myself jolted out of a trance, suddenly conscious again of where I was and what had to be done. Morale soared: Ikummaq searched for ringed seal pups - a delicacy among the Inuit - and Beedell, to celebrate April Fool's Day, stripped naked and streaked around a piece of pressure ice in a demonstration of Arctic hysteria that left the dogs in a state of nervous bewilderment.

Arctic

madness

Corel

photo

The mood, however, did not last for long. Once on Borden Peninsula, the tempo became one we called "bump and grind." In some spots, we found ourselves floundering through knee deep soft snow or grunting up long, steep inclines, while in others - notably some ice-wreathed boulder fields - we became adept R.A.T. (Rock Aversion Technique) patrollers, leaping on and off the sled to guide it and the dogs through rough spots and then prying the sleds off or out from between the boulders when our guidance failed. Our skills were thoroughly tested when we left the peninsula, following an unnamed stream that drained into Adams Sound. The descent began gently enough but became progressively steeper and rockier and culminated in a windswept rock garden between steep canyon walls. Beedell and I were soon off the lurching sled, shouting at the dogs and struggling furiously to control the sled's momentum and to steer it through the boulders, all the while trying to stay nimble enough to avoid being crushed. When Beedell broke through some weak ice, smashing headfirst into the snow, the team hurtled on and I lost whatever control of the sled we had had to that point At about the same time, Immaroitok and Ikummaq's sled flipped, and only Immaroitok's lightning fast reflexes and a handspring that would have done justice to an aspiring Olympian kept him from being killed beneath it.

Once the run was over and the adrenaline had subsided, I marvelled at our sleds. The qamutiik had taken an incredible beating yet had sustained little damage. Constructed of few parts and lashed, rather than nailed or pegged, they had held up to abuse that would have reduced any other type of sled with an equivalent load to matchsticks.

Our arrival in Arctic Bay was gloriously chaotic. Snowmobiles raced out to greet us, hordes of children scrambled onto the sleds, and when the dogs halted, the rest of the 500 strong population pressed in to congratulate us. As in Pond Inlet, we used our few days there to rest, eat and take on another load of frozen seals for dog food. Beyond its importance to us as a resupply point, Arctic Bay also had historical significance for our journey. In a nearby (and now abandoned) camp named Uluksan, Qitdlarssuaq, after his confrontation with Ikieraping’s relatives, had decided that only by crossing Lancaster Sound to the hinterlands of Devon Island would he be safe from further pursuit.

Corel

photo

…to be continued