Table of Contents

*

Featured Inuit Dog Owner: Ken MacRury, Part 1

*

Remembering Niya

*

Page from the Behaviour Notebook: Bishop and Tunaq

*

Antarctic Vignettes

*

On Managing ISD Aggression

*

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part 3

*

News Briefs:

Inuit Dog Thesis Back in Print

Nunavut Quest 2003 Report

Article in Mushing Magazine

Possible Smithsonian Magazine Story

*

Product Review: Dismutase

*

Tip for the Trail: Insect Repellents

*

Book Review: The New Guide to Breeding

Old Fashioned Working Dogs

*

Video Review: Stonington Island, Antarctica 1957-58

*

IMHO: The Slippery Slope

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Ken standing by traditional seal skin

harnesses and tug

lines Feder photo

Ken MacRury, Part 1

TFH: What brought you to the Arctic? When did you

first arrive? Back

then did you ever imagine you'd have stayed for as long

as you did?

KM: My wife Sheila and I first went to the Arctic

(Frobisher

Bay - now Iqaluit) in 1971 after working as teachers in

southern Canada

for two years, following university. We expected to

stay for the

normal two years and never dreamed that our stay would

last our entire

working career of thirty-one years.

TFH: How did your interest in Inuit Dogs develop?

KM: In 1974 we moved north to Igloolik at the top

of Foxe Basin,

a wonderful traditional community where, for the first

time, we came into

contact with real dog teams and real dog drivers. I was

able to apprentice

to a terrific hunter and dog driver, Pauloosie

Attagutalikkutuk and, over

the next two years, spent considerable time traveling and

hunting with

him by dog team in a very traditional manner. I learned

much from him in

those two years we spent in Igloolik - about dogs, about

sleds, about hunting

and mostly about patience and humor and how to apply them

when living where

you have at best only very limited control over how your

world unfolds.

TFH: What role did you play in the Eskimo Dog Recovery

Project?

KM: When Bill Carpenter came to Igloolik looking

for pure stock

in 1975 and 1976, I assisted him in meeting the right

people. Later we

exchanged breeding stock and worked to support each other

in preserving

the breed.

TFH: What made you decide to choose the Inuit Dog as

the subject

of your master's thesis? Did you ever imagine that your

research would

have such a lasting effect on such a wide

audience?

KM: When I went to Cambridge, UK, in 1990, I

planned on doing

my thesis on "The Inuit Land Claim and Its Impact On

Division of the Northwest

Territories" or some such topic. The topic was not

approved by the

Board of Graduate Studies, as there had been several

theses in recent years

on the Inuit Land Claim, and they decided that there would

be none further

until the Claim was implemented. My thesis adviser

was aware that

I had been doing some private research on Inuit Dogs and

suggested they

could be the topic of my thesis. We then made a

second submission

to the Board of Graduate Studies and the topic was

approved. At the

time I had no idea that the thesis was ever likely to be

published and

certainly not go to multiple printings.

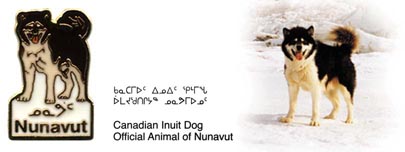

Ken's dog Ruff was used as the model for

Nunavut's Official

Animal and for this cloisonné pin

TFH: Since the Inuit Dog became the Official Animal of

Nunavut, has

the Nunavut Government made any effort to encourage the

pure breeding of

stock and to encourage owners to protect against

needless deaths by vaccinating

against preventable diseases?

KM: Vaccination is made available to team dogs

through the Department

of Sustainable Development, the wildlife officers. I

am not aware

of any efforts on behalf of the Nunavut Government to

promote pure breeding

of the Inuit dog.

TFH: What was your feeding regimen at different times

of the year?

KM: Starting in October, when the team came home

from Holiday

Island, I would feed them every two or three days on

thawed cut up meat

(usually seal but also walrus, whale or fish, rarely

caribou). By

mid-November I would be feeding every second day and that

would continue

all winter until at least the end of March. When

feeding, each dog

would get a mix of meat, bones, organs that had been

thawed out.

The amount would be about three pounds per day per

dog. After April

the feeding could be more erratic as we would be traveling

more and putting

in longer days in harness. At that time of year the

dogs might be

fed every day or not for three or four days and amounts

would also vary

from 3-4 pounds per feed to 8-10 pounds per feed. In

general they got what

they needed and sometimes if we were trying to get rid of

meat before it

got too spoiled they might get as much as they could eat

and more left

over. The dogs would be working until the end of June and,

after a short

wait of ten to fifteen days for the ice to clear, would be

moved out to

the island where they would spend the summer/fall,

mid-July until about

the third week in October. During that time they

would be fed about

once per week if they were all adults. If there were

juveniles on

the island I would feed about twice per week. In

either case I would

take a large bin of meat to the island, perhaps 60-70

pounds and what they

did not eat immediately would be left for later but I

suspect the ravens

and gulls got most of the leftovers. Usually, I would have

six to eight

dogs on the island. I would sometimes take out to the

island a whole seal,

not cut up. As the dogs stood around me I would cut

the seal and

feed them individually by hand while calling their

name. I felt this

reinforced my position, made them remember their training.

It gave me an

opportunity to favor the boss dog but at the same time

remind him that

I was in charge.

On Holiday Island, Ken's team eagerly

awaits his arrival

with their food Feder photo

TFH: How did you train your dogs?

KM: I would start to train the pups as soon as they

took solid

food. I would raise the pups together, never alone

or one pup at

a time. They would be taught to take food from my

hand, never to

grab and to wait their turn. Also they were taught to come

to me when I

called them by name. After that most training was

done by the adults

when the pups were taken with the team - to never stop

until I told them

to stop, to lie down when stopped, not to fight when in

harness, to follow

the leader at all times, not to chase caribou, etc.

Once you have

an experienced team it is very easy to train young

dogs. And if they

are too unruly to fit in or too lazy to work then they can

always be sent

somewhere else and often they will make excellent team

dogs for someone

else.

As the driver it was very important to me to have a team where two positions were absolutely clear: the leader and the boss. I decided who was the leader and I did what was required to ensure the leader felt secure and happy being leader. I believe there are three requirements to be a good leader: a desire to be out front, a desire to please the driver and intelligence. Without all three the leader will never be very good. A good boss dog is critical to a well-ordered team, for without one the team will verge on anarchy all the time. When you have a good boss dog there will be a calm order in the team as the boss will not allow others to fight and will not start fights himself. I had actually gone for years without serious fighting, all due to having an undisputed boss who ran the team with quiet authority. One of the keys to having a well-established boss is to allow the dogs to have extensive opportunity to interact with each other without human interference. If we are forever rushing in to break up every squabble, it does not allow the natural boss to emerge or the team social structure to develop. (Just throwing all the dogs in a cage is a recipe for some serious injuries.) We have to be confident enough in the process and accept the fact that some dogs may get hurt in the process. But in the end it will be a far better team. Each summer my team would spend three-and-a-half months on an island in Frobisher Bay, visited once or twice a week, and would have lots of time and opportunity to sort out the boss question. When that process is in play the losers must have the opportunity to put some space between themselves and the others. If I had not placed nine-year-old Goofy, an aging co-boss dog, when I did, it was very unlikely that he would have survived another year. His brother (and co-boss) had died and he was becoming too slow to keep up with the younger dogs. When a boss dog is deposed he doesn't go to the number two slot, he tumbles all the way to the bottom. It is a sad sight to see an old boss being picked on by young dogs hardly more than pups. It would not have surprised me at all if Goofy had simply disappeared from the summer island, either killed by the other males or forced off the island and drowned.

One caution about boss dogs: there are the rare bullies that do not exert quiet authority but take every opportunity to fight the lower dogs and often do damage to them. Most often these are young aggressive dogs that have not had a good role model or older bosses that are losing their grip on power. In either case they can be dangerous and are best disposed of.

TFH: Please describe for us some details of a good

harness fit. The

traditional harness is quite “economical” in design,

perhaps born out of

necessity since they were originally made out of bearded

seal. Modern so-called

freighting harnesses can be described as more

“elaborate”, but do you think

they are any better for the dog? Do you think that it is

better for dogs

run in tandem?

KM: I always used the traditional sealskin harness

in the colder

weather - October until end of April or so - and switched

to a nylon webbing

harness made in the traditional style for May and

June. I did that

as the sealskin harnesses would have to be dried after

each use in the

spring. That shortens their life and as the older

hunters die it

is becoming harder to get the sealskin harnesses.

The traditional harness is made of one piece of bearded sealskin about four inches wide and three feet long. It is split almost in two lengthways and then the loose ends are sewn back to the sides, a short piece (about six to eight inches) is sewn across the back of the neck and two thin and short adjustable pieces are tied in slits in the main harness across the chest. The whole harness has four pieces. Also there is a tail piece of sealskin rope about 12-16 inches long with a moon shaped toggle of caribou antler or muskox horn attached to it. About fit, it is absolutely essential that a harness fit well if one wishes to get the most out of the dog. The traditional harness was fitted to each dog individually; no such thing as small, medium and large. And it was fitted at the first of each year and on a regular basis during the year as the dog's size changed. The better drivers had a stock of harnesses and I often saw them change a harness when they noticed a poor fit. The sealskin harnesses would mold themselves to fit the dog like a well fitting glove. Adjustments were made to the chest pieces if that was the problem but otherwise the entire harness was changed if the length was not right or the neck strap was too short or long or if the leg hole was not right. Fit is very important and great care is taken to get it right. In my view, the modern harnesses are made for loping or running dogs pulling light loads over good trails. The Inuit dogs pull more with their shoulders and push into their harness. Therefore, they will be more comfortable with a harness that is wider across the neck and is hinged at the chest to allow individual front leg/shoulder movement. The Inuit harness is also best when used with individual traces which allow a greater distance between the pull point and the dog. The harness can then be placed higher on the back as the angle of pull is not as extreme. This allows for more force to be exerted on the load.

I always ran my dogs in a fan hitch and have no experience with tandem. I do think that using the fan hitch allows a lot more interaction between the dogs. I often noticed that when we would be stopped, certain dogs would lie beside their friends although when running they might be separated by quite a distance. I think my dogs were happier in a fan than they would have been in tandem. But then, I never ran where there were trees.

Traditional bearded seal harness, toggle

made from sled

runner plastic,

not

bone

Hamilton

photo

In part 2 of this F.I.D.O. Ken describes the kind of dog that successfully made it onto his team. He talks about purity, the role of genetic diversity, the future of the breed in the Canadian Arctic, and what breeders in the south need to do in order to "substitute" for the lack of culling by the nature of the North.

Editor's note: In the summer of 2002, Ken and Sheila MacRury said good-bye to Iqaluit, retiring to a small community in Atlantic Canada. Although he sold his team to a musher in Iqaluit, Ken took Mabel his lead dog with him.