Table of Contents

*

Featured Inuit Dog Owner: Ken MacRury, Part 1

*

Remembering Niya

*

Page from the Behaviour Notebook: Bishop and Tunaq

*

Antarctic Vignettes

*

On Managing ISD Aggression

*

The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, Part 3

*

News Briefs:

Inuit Dog Thesis Back in Print

Nunavut Quest 2003 Report

Article in Mushing Magazine

Possible Smithsonian Magazine Story

*

Product Review: Dismutase

*

Tip for the Trail: Insect Repellents

*

Book Review: The New Guide to Breeding

Old Fashioned Working Dogs

*

Video Review: Stonington Island, Antarctica 1957-58

*

IMHO: The Slippery Slope

Navigating This

Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The

Fan Hitch

The Fan

Hitch home page

ISDI

home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Vignettes from Another Time, Another Place

A "youth gang" investigates the local

fauna

G. McLeod photo, 1962

Feeding dogs Nutty (pemmican)

The dogs are fed 450 gm blocks of Nutrican pemmican during

a

journey.

Each dog receives one block a day for two days and two

blocks on the

third

day. The food provides an average of 3,300 calories per

dog per day.

They

eat snow to rehydrate themselves. When thirsty their fur

becomes stiff:

well hydrated, their fur is silky. On the first day of a

journey we

remove

the thin paper wrapper from each block of pemmican so that

it does not

clog with the seal meat and bone remaining in their

stomachs from the

last

meal they had on base. The second day out we walk

down the night

span chucking each dog a paper wrapped block. The dogs

pounce on the

welcomed

food. Most crunch up the paper and the pemmican and

swallow it all.

Some

stand over the block, front legs straight, pressing it

into the snow

with

front paws while carefully removing the paper with their

incisor teeth.

The wrapper is discarded, and the block is consumed.

Isobel, I

have

noticed goes to the trouble of removing the wrapper then

eats it as a

starter

before the main pemmican

course.

Nick Cox

Stitching Dogs

We had checked the night trace but had not noticed that

some of the

chains are too long. Mac and Dex could just touch noses

and began to fight.

Mac got a hold of Dex by the nose, his jaws clamped tight.

Mac immediately

adopted that superior, blank, glazed stare. Like a

wrestler who had

his opponent in a perfect hold, enjoying the moment at the

expense of the

other's discomfort. Poor Dex squealed with pain, his

eyes focusing

all to closely on the line of teeth across the bridge of

his nose. We freed

Dex by inserting the back end of a ski between Mac's jaws,

levering them

gently open.

The fracas over, both dogs looked very pleased with themselves. Both sitting and wagging their tails with gusto while looking alternatively at me and each other. Mac had a big grin on his face, a string of blood stained saliva hanging from one side of his mouth. Dex was also grinning. There was a large hole in the bridge of Dex's nose, right between his eyes, the displaced flesh standing on end like the jagged top of a newly opened baked bean tin.

Settled in the tent, we prepared room indoors for Dex who would need a stitch in his wound. I filled a syring with 2ml acetylpromazine which would make Dex drowsy. I put the loaded syringe in the lunch break (vacuum) flask to help prevent the fluid from freezing at the base of the needle when I climbed into the cold air outside. I tied Dex on a short lead to the back of the sledge and injected the drug into his back leg. During the half hour it takes for the drug to take its effect, we cleared a space near the tunnel entrance to the tent. Dex was quite wobbly on his legs when I dragged him into our snug and warm world indoors. I dripped a little local anesthetic on the wound then waited a while Rudy sat astride the recumbent Dex and pushed the dog's head firmly onto the groundsheet. Waiving a needle and thread so close to his eyes it was important he stayed very still. The stitch work was far from smart but it pulled all the bits together and with a sprinkling of antibiotic powder on top, his face looked less of patchwork. Dex slept soundly in the tent. The doping drug we gave him takes a few hours to work off and during that period a dog lacks the ability to maintain its correct body heat. We had supper, melted ice in the billy ready for the morning brew, then slept.

The morning call was sudden and not as usual by the nasty Little Ben alarm clock perched on the pots box between us, but by a very wide awake and playful Dex, whose large square frame stood over me. Repeatedly he brought a front paw down in the middle of my chest. I sat up and cuddled his large wolf head. He then leapt over to see Rudy, sending primus, matches, meths, candle, and Little Ben flying. He then went round and round the seven foot square tent, stampeding over everything, including us, at every lap. I took him back to the night span. The wind was very strong. Nick Cox

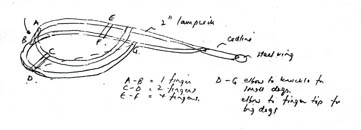

Sketch of a lampwick harness with

dimensions

Training a Lead Dog With the Help of Doughnuts

(Smultring)

Niveak was a large deep chested dog who, we were told, had

led a team

for his previous owner for the past three years. Second

hand dog salesmen

are not unlike those who sell cars. Niveak meandered about

ahead of our

team oblivious of any commands we gave him. For

weeks Knut perservered

but there was little improvement. One morning before we

harnessed up the

two teams he had an idea. We received a bag of stale bread

from a local

supermarket which we occasionally gave to the dogs with

the dried fish

we got from Tromso. The last load they gave us included a

sack of smultring

(doughnuts) which we were going to throw out. Knut put a

dozen or so doughnuts

into a large white paper bag which we threw on the sledge.

The teams harnessed

and ready, he set off with Niveak leading. The giant Knut

sat cross legged

in the middle of his Greenland sledge cradling the

bag of doughnuts

in his lap. He said the bare minimum to his team,

expert at judging

when they were absorbed in their work, knowing when a word

from him would

interrupt their concentration. He called a command to

Niveak. "Hoyre" (right)

"Niveak". Like a ship responding to its wheel there is

sometimes a delay

before the turn comes. But in Niveak's case the wait would

go on forever.

There was no deflection from the route they were taking.

It was time for

the doughnuts. Knut shouted "Hoyre, Niveak" and threw a

doughnut ahead

and to the right. Niveak turned towards the doughnut

leading the team and

sledge behind him. The doughnut was scooped up and eaten

on the move and

the new course was set.

The doughnuts worked well left and right, and Niveak returned that afternoon having navigated a complex route of many miles. Knut knew from the start that it was Niveak's grand finale as a leader. A few journeys like that and he would be too fat to go anywhere. Nick Cox

A "Signature" Trail

Little Jock was rather shorter in the leg than most and

his chief claim

to fame was that in soft snow his penile member appeared

to plough a distinct

furrow down the center of his track when pulling a sledge.

As he insisted

on pulling well wide of the rest of the team it was always

very noticeable

but in no way was this detrimental of his ability to make

use of

it.

Jimmy Andrews

A Memorable Day!

It was less than a month from mid-winter so with limited

daylight only

a few hours of safe travel were possible each day. On this

occasion there

were two of us with two sledges and two teams. We

started the day

with a long, fast and very bumpy decent down a long slope

leading on to

the glacier. I was riding on the back of the sledge and

well remember the

sledge wheel breaking loose from its frame and passing me

at high speed.

It was last seen rolling off into the far distance and was

never seen again.

Also the dog Sherakin [was] strapped to the back of the

sledge as he was

very weak and ill and had to be physically restrained from

taking his place

in the team which would have weakened him even more. The

glacier we were

crossing was known to be badly crevassed so, after working

our way to the

middle, both sledges were stopped to assess the next part

of the route.

The day was dull and overcast, poor weather for working

among crevasses.

I was standing on my skis to the left and slightly behind

my sledge when

suddenly there was a noise - whoomph - and I was left

standing on the edge

of a deep hole with the tips of my ski over the edge of

what seemed a wide

and bottomless crevasse. The center of the bridge

had fallen away

leaving the sledge supported at its front and rear only.

For the time being

it did not look as if the sledge would fall further which

gave us time

to work out a method of retrieval. This was not easy

as, if the sledge

were to be moved a foot or two forward, the rear would

fall in and the

opposite would happen if we moved it backwards. There was

no way we could

get closer to the sledge to reduce its load. We decided

that the only solution

was to start the sledge with such power that it would

clear the crevasse

before the back end had a chance to fall in.

To give ourselves a chance of success we let the dogs rest for a while and then the driver of the leading sledge walked out a short way ahead of my dogs. On the command to go the other driver called to them, I gave a strong push from the rear and with an uncertain lurch my sledge cleared the crevasse.

A truly memorable day and not one I would like to repeat! Roger Scott

Scott's sledge spans the cravasse on

Swithinbank Glacier,

1973 Scott photo