Editorial: We’ve Moved!

Historic Ceremony in Kangiqsualujjuaq

Passages: Heiko Wittenborn

In the News

Point of View: Veterinary Service in Nunavik

Chinook Project: Summer 2011 Report

Unikkausivut: Sharing Our Stories

Making a Mitten Harness

Media Review: Martha of the North (video)

IMHO: Historical Perspective or Hyperbole

Index: Volume 13, The Fan Hitch

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

ISDI home page

Editor's/Publisher's Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal of

the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four times

a year. It is available at no cost online

at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Photo: Évangéline DePas

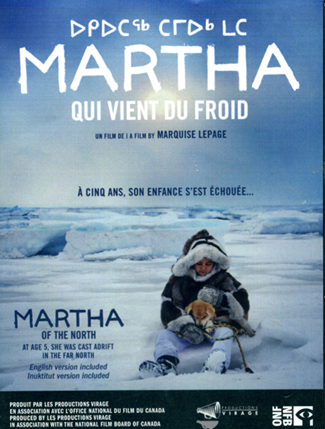

Martha of the North

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

"The deportation of Inuits (sic) to the Far

North is one of the worst human rights violations

in Canadian history."

in Canadian history."

Ottawa

Citizen

April 3, 1993

April 3, 1993

Martha of the North is the story of the Canadian government's Inuit relocation project as told through the experience of Martha Flaherty who, as a five-year-old accompanied her parents and siblings along with other Inuit families to a place in the Canadian high Arctic based on the government's false promises of a better life.

In the mid-twentieth century many circumpolar nations had their eyes on Canada's high arctic islands. But an international tribunal ruled that only permanent human settlement could assure a nation's sovereignty. Martha of the North suggests that the seeds of the government's solution may have been planted in 1922 when Robert Joseph Flaherty's Nanook of the North, filmed in Inukjuak, Arctic Quebec (now Nunavik) gained world-wide attention. Flaherty's iconic classic introduced the outside world to the lives of the Inuit, portraying them as hearty and cheerful inhabitants surviving in a savagely harsh environment.

Wildlife biologists understand that successfully releasing captured animals back into the wild depends on their ability to quickly adapt. Reintroduction must be at an optimal time of year, with support from well established colonies of the same species, a compatible environment and availability of food resources. But whether the Canadian government's failure to apply the same humane principles to the relocated Inuit was outright stupidity or malicious indifference or both, is not clear.

Family and community are the heart and soul of Inuit life. And in 1953 it was a litany of lies that lured several Inukjuak families into an "experiment", later widely described as an exile, that took them from their homes below the Arctic Circle at 58E 28'N where there was day and night every 24 hours, plentiful and various animals to hunt, grass to walk on and long periods of open water in the summer to a spot at 76E 24' N (1243 mi/2000km north) whose translated name means "the place that never melts". It was a place which had been declared a wildlife sanctuary where the hunting of musk ox was forbidden and the caribou hunting season (which had ended prior to the families' arrival) was limited to one animal per family per year. These details were never forthcoming to the families. What they were told was that the location was selected (by experts) to improve their lives, offered plentiful food resources, that families would not be separated and that they could return in two years if they so chose…all lies.

The Inukjuak transplants were indeed broken up, some being left at Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island while other sent even farther north to Grise Fiord on Ellesmere Island. Bitter cold came well before adequate snowfall offered the ability to build igloos, so the people were forced to live in tents, woefully inadequate protection from the fierce winter weather. Unfamiliar with three months of total darkness, navigating unfamiliar and difficult landscapes to hunt for food and find fresh water icebergs was difficult, dangerous and deadly. Men, proud and successful hunters of Inukjuak, had difficulties feeding their families and were humiliated by their failures. Everyone was always cold and hungry. Those that wished to return home were told they would have to pay their own way, which was of course impossible. The people suffered both physically and mentally; so many broken lives. Adults and youngsters died of illness, accident and suicide.

It wasn't until 1962 that prefabricated housing was constructed and in 1987 that the government allowed the displaced families to live wherever they chose. In 1993, largely due to the efforts of Inuit activists, who themselves were among the arctic exiles, the Royal Commission on Inuit Arctic Relocation was established. There was a financial settlement awarded but it wasn't until August 18, 2010, two years after Martha of the North was completed, that the much sought after official apology was finally delivered.

Robert Flaherty died in 1951, four years before the second wave of Inukjuak families, including his son, Martha's father (born to Nanook of the North's leading lady, Martha's grandmother, in 1922 after the filming), and Flaherty's grand daughter, Martha, were sent north to misery. After filming Nanook, he never returned to Arctic Quebec to see his son, nor did he live to learn the impact his film would have on the people of Inukjuak.

Martha of the North is captivating even if the theme makes it uncomfortable to watch. It is an artful blend of archival and present day still images and movie footage, narration and testimony by many Inuit who lived through the era. And it serves as a testament to the tenacity of Inuit for not only surviving under such dreadful circumstances, but also for pursuing and eventually receiving the redress they long sought. As such, it is a film which offers history that needs to be seen to be better understood and respected.

I am reluctant to divert attention from the focus of this film, however I can't help but mention here that there are many images of dogs in Martha of the North and I found it noteworthy to see the change in them from the early 1950s to the time of this film's creation, around 2008.

Martha of the North (83 minutes), a Virage Production in association with the National Film Board of Canada, is to be included in the National Film Board of Canada's Unikkausivut: Sharing our Stories project, but it is available to purchase now. Prices and availability vary depending on whether the purchase is for home or institutional viewing and also varies by country. Canadian purchases can be made directly from the NFB store or by calling 1-800-267-7710. U.S. buyers should call: 1 800 542-2164. All email inquiries can be directed to info@nfb.ca or mailed to: National Film Board of Canada, P.O. Box 6100, Downtown Station, Montreal, QC H3C 3H5, Canada.