From the Editor... Words Worth Repeating

Qillarsuaq

The Endurance Dogs

The Concept of an Aboriginal Dog Breed

Inuit Tradition in 75 Tons of Sand!

The Canadian Animal Assistance Team’s 2013 Northern Canada Animal Health Care Project

Far Fur Country Project Update

Movie Review: Arctic Dog Team, Arctic Jungle, Arctic Hunter

IMHO... Well, That's The Way We Do It!

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

from The Daily Chronicle

The Endurance Dogs

by Robert Burton

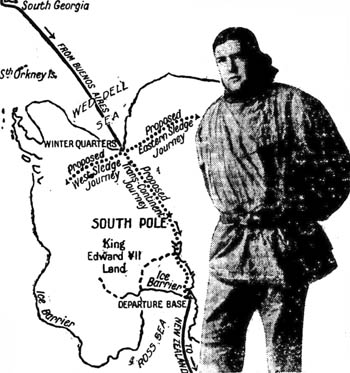

2014 is the centenary of Shackleton’s departure on his expedition to attempt the crossing of Antarctica. The story of how his supreme skill as a leader rescued his men will be retold many times. The men did not even land on Antarctica. Their ship Endurance became trapped in the pack-ice almost within sight of land and was swept northward until the overwhelming pressure of the ice crushed her. The men escaped onto the ice and continued the drift northwards until they could take to three small boats and land on desolate Elephant Island. Shackleton then sailed in one of the boats, the James Caird, across stormy seas to South Georgia to arrange his men’s rescue.

But what would have happened if they had managed to land on the coast of Antarctica and set out across 1800 miles of white wilderness? Would they have ever been heard of again?

I have been looking at Shackleton’s plans to shed some light on this question. One aspect was his dogs. It had taken Amundsen's successful journey to the South Pole to convince Shackleton that dogs would be the key to crossing the continent.

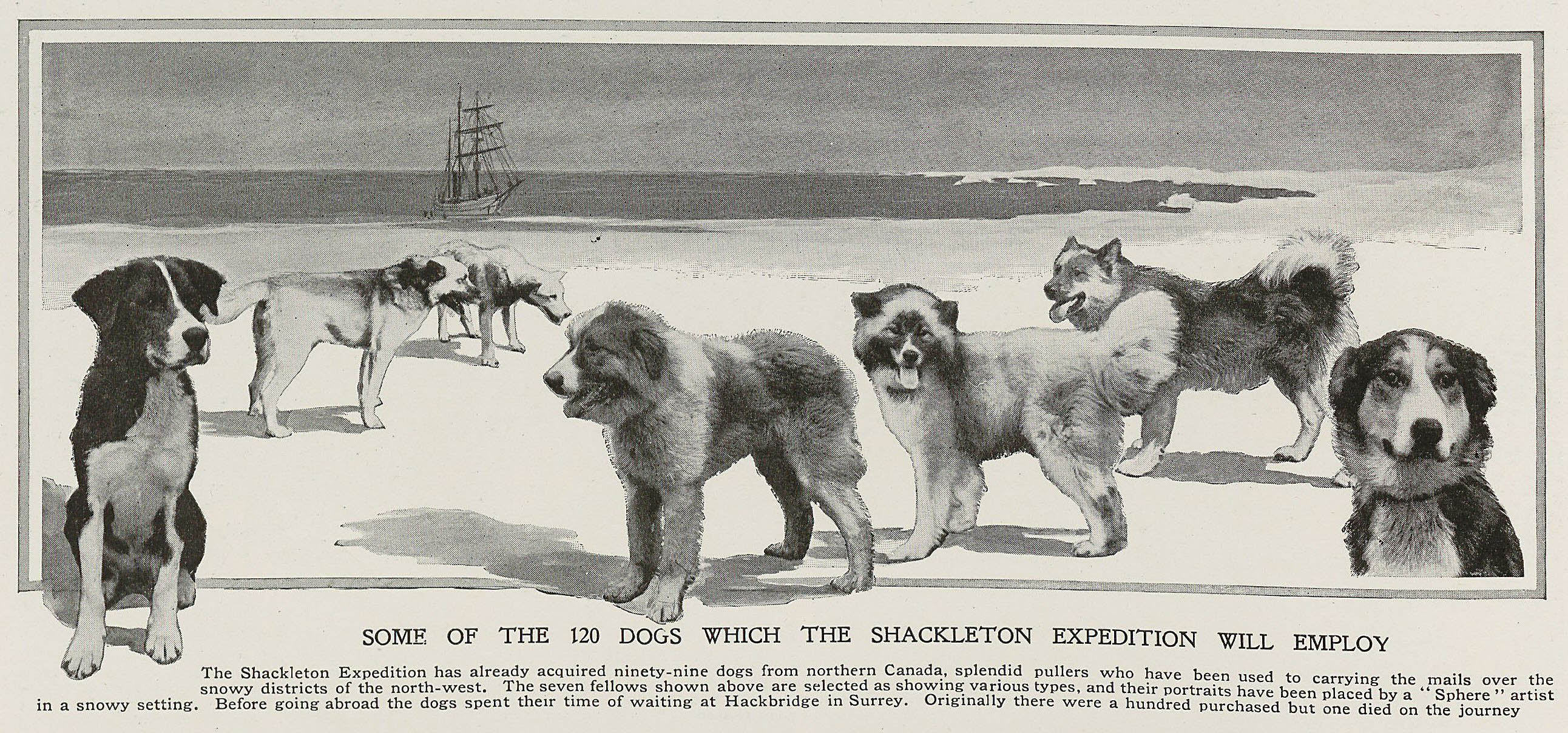

When Endurance set sail from the island of South Georgia on 5 December 1914 and headed for Antarctica she was carrying 68 dogs. This was not the intended complement. Shackleton’s first plan was for 120 dogs but he instructed the Hudson's Bay Company in London to secure only 100 dogs suitable for pulling sledges. The task was entrusted to Sandy McNab, a Hudson's Bay man, who travelled around fishing villages on the western shore of Lake Winnipeg. Accompanied by two of the local dog handlers, he bought the healthiest and most intelligent dogs, for which he paid good prices to persuade men to part with their best dogs.

Image caption text - SOME OF THE 120 DOGS WHICH THE SHACKLETON EXPEDITION WILL EMPLOY

The Shackleton Expedition has already acquired ninety-nine dogs from northern Canada, splendid pullers who have been

used to carrying the mails over snowy districts of the north-west. The seven fellows shown above are selected as showing

various types, and their portraits have been placed by a “Sphere” artist in a snowy setting. Before going abroad the dogs

spent their time of waiting at Hackbridge in Surrey. Originally there were a hundred purchase but one died on the journey.

from The Sphere

The dogs were transported in cattle trucks to Montreal and thence to England on the Montcalm. They were fed on fish and dog biscuits which they took some time to learn to appreciate. When they reached London, crowds came to visit them. Ninety-nine dogs were landed; only one had died en route. Thirty of the remainder were then earmarked to be sent with the support party that was headed to the Ross Sea*, where depots would be laid for Shackleton’s party to pick up on the way across the continent. Now only 69 dogs would go south on Endurance.

Problems started when Shackleton was unable to procure the services of an experienced dog-handler. He would have liked to sign up one of the Canadians who had brought the dogs to England. Two would have been willing but they had recently married and were expecting their first children. One did wire his wife, who replied, "Come home." So Shackleton telegraphed two other men at Lake Winnipeg, but neither was interested. According to the memoirs of Frank Wild, the second in command, Shackleton had actually engaged one of the men to accompany the Expedition. Wild wrote that the man asked him ‘all about conditions in the Antarctic. When he learnt there were no trees, no moss, no grass, he asked in a surprised tone, “What do the moose live on?" & when I told him there were no moose or any other animals he said “Hell! I’m off back North", & he went.’ There is no mention in this in the Canadian’s own reminiscences; only the call of family duty.

Frank Wild also described the dogs as ‘a mixture of wolf & almost any kind of big dog, Collie, Mastiff, Great Dane, Bloodhound, Newfoundland, Retriever, Airedale, Boarhound, etc.’ This also seems to be something of an exaggeration, although pictures do show a preponderance of collie mixed with husky.

The failure of any experienced dog-handler to accept the invitation to join the expedition might have seriously affected the efficiency of the continental crossing party. Shackleton records in South that 'worm-powders were to have been provided by the expert Canadian dog-driver I had engaged before sailing for the south, and when this man did not join the Expedition the matter was overlooked'. I think Shackleton has glossed over the fact that he never did engage a dog-driver. In the event, the ever-capable Frank Wild was put in charge of the dogs.

During the month that Endurance spent at South Georgia on her way south, the dogs were fed on whale meat, and a ton of it was suspended in the rigging when she set sail, out of reach but not out of sight or smell of the frustrated dogs penned below. When the whale meat was finished, the plan was to shoot seals resting on the ice floes but circumstances prevented this and the dogs had to be fed on Spratt’s dog biscuits.

As Endurance proceeded farther into the pack-ice, the dogs started to lose condition - ‘getting run down and mangy’. Eventually some died naturally and others had to be shot. Post-mortems were carried out by the expedition’s two doctors but specimens, reports and the diaries of both doctors were lost after Endurance sank. From comments in the diaries of other expedition members, based presumably on what the doctors told them, the problem was a severe infestation with worms. Frank Wild considered they had picked up tapeworms from eating rats at South Georgia, and it is possible they could have contracted tapeworms from rat fleas, the intermediate host, but the diaries record three types of worms: tapeworms and roundworms in the gut and a ‘vile red worm’ in the blood vessels. Dr. Gary Conboy of Atlantic Veterinary College at the University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PEI, Canada suggests that the red worms were probably the roundworm Dioctophyme renale, commonly referred to as the "giant kidney worm". It is almost certain that the dogs had brought a burden of these worms with them from their native Canada.

Did the dogs die of worms as is often claimed in the retelling of the Endurance story? Unlikely. The sight of the worms would have made a great impression when the post-mortems were made but is axiomatic that parasites do not kill their hosts – that would be suicide! – unless the host is diseased or malnourished. I thought at first that the dogs might have lost condition because they were fed on 1½ lb biscuits a day rather than seal meat and blubber, but other expeditions fed their dogs on the same biscuits without such disastrous consequences. Moreover, I have ascertained from the expedition diaries that seals were being shot for dog food before the deaths occurred, so it is very unlikely that malnourishment was the problem. There is the possibility that the serious loss of condition was due to some disease that had been lying dormant. Distemper is one possibility.

By this time Endurance had been trapped in the pack-ice and any hope of making the crossing had gone. We will never know for certain what afflicted the dogs but the bottom line was that there were now only 50 dogs and eight pups, so Shackleton was left with half the number originally planned to convey him across Antarctica. And he could have lost more at a later date. Surely this would have put the success of the expedition in jeopardy.

Bob Burton wintered in Antarctica 50 years ago and has been interested in polar history ever since. In the 1990s, he was Director of the Museum at South Georgia where Shackleton is buried. He continues to visit Antarctica and South Georgia as a lecturer on cruise ships. He lives near Cambridge, England.

* Ed: For more background on Shackleton’s attempt and the Ross Sea party visit The Lost Men book review and The Lost Men website.