From the Editor... Words Worth Repeating

Qillarsuaq

The Endurance Dogs

The Concept of an Aboriginal Dog Breed

Inuit Tradition in 75 Tons of Sand!

The Canadian Animal Assistance Team’s 2013 Northern Canada Animal Health Care Project

Far Fur Country Project Update

Movie Review: Arctic Dog Team, Arctic Jungle, Arctic Hunter

IMHO... Well, That's The Way We Do It!

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

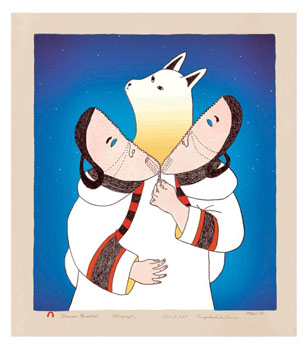

Shaman’s Dance

Pitaloosie Saila, 1970; stonecut on paper, 24 x 18 in;

reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

Qillarsuaq

by Kenn Harper

The Inuit known throughout history as the Polar Eskimos, and who in more recent times have been known as the Inughuit, live in north-western Greenland, farther north than any other civilian population on earth.

Before contact with white explorers, their world was a narrow strip of coastline bounded on three sides by glaciers and on the fourth by the sea.

For reasons not known, by the mid-nineteenth century they had lost much of the material culture on which other groups of Inuit traditionally relied — the qajaq and the larger so-called woman’s boat, the umiaq, as well as the bird spear, fish leister, and bow and arrow.

The loss of sea transportation gave them a lifestyle different from other Inuit. It confined them to land during summer, where they survived on food cached during the long, sun-filled spring. The absence of the bow and arrow prevented the hunting of caribou.

Consequently, the Inughuit were primarily sea mammal hunters. They had adapted to their technological losses, but survival was difficult and the population was in decline. A fortuitous immigration of Inuit from Baffin Island in the 1860s alleviated their harsh conditions by reintroducing the technology that they had lost.

The migration was led by a shaman, Qillaq, more commonly known by his Greenlandic name, Qillarsuaq (also spelled Qitdlarssuaq), and it led from northern Baffin Island to north-western Greenland.

Qillarsuaq, however, was not a native of northern Baffin Island, but an Uqqumiutaq, a person from south-eastern Baffin Island. He may once have lived in Cumberland Sound. It is known that his son, Ittukusuk, was born at Cape Searle, an island off the north-eastern tip of Padloping Island, south of present-day Qikiqtarjuaq.

Research by Michael Hauser, a Danish ethnomusicologist, indicates that Qillarsuaq’s roots may go farther back, south-west to the Cape Dorset region. Hauser found marked similarities in the styles of drum dancing used in Cape Dorset and the Thule District of Greenland, but nowhere in between.

Qillarsuaq’s murder of a fellow Uqqumiutaq, probably between 1830 and 1835, caused his sudden departure north to the Pond Inlet area with his accomplice, Uqi, and their families and followers.

Some years later, near Pond Inlet, a party of their enemies attacked them in a memorable battle in which Qillarsuaq and his group survived by taking refuge on an iceberg. Once again, they fled for safety, first heading in the direction of Igloolik but eventually crossing Lancaster Sound to Devon Island.

On Devon Island in the summer of 1853, near Dundas Harbour, Captain Edward Inglefield of the Phoenix met a group of twenty-five Inuit men, women and children, led by Qillarsuaq. Were it not for the chance meeting with Inglefield, Qillarsuaq and his followers may well have remained on Devon Island.

Although Inuit legend tells of spirit flights in which Qillarsuaq learned that there were Inuit living far to the northeast, it is more likely that he learned this from Inglefield and his Greenlandic interpreter and possibly by a perusal of the explorer’s charts.

Nevertheless, even with his new-found knowledge, Qillarsuaq was in no hurry to leave the south coast of Devon Island, an area rich in game. Five years later Francis McClintock, an officer in the British navy, met him at Cape Horsburg, only fifty miles from Dundas Harbour.

Shaman Revealed

Ningeokuluk Teevee, 2007; lithograph on paper 51.5 x 46 cm;

reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts.

It was probably in the spring of 1859 that Qillarsuaq began his great journey from Devon Island in search of the new land and the people that he knew to be farther north. Accounts vary, but probably he led a group of 50 to 60 people, which included his friend Uqi and his followers.

Qillarsuaq was already old. McClintock had noted that he was bald, unusual among Inuit, and that his few remaining hairs were white. But he was a born leader, remembered as someone to be “feared and obeyed”.

At the island of Ingirsarvik, at the mouth of Talbot Inlet off the east coast of Ellesmere Island, Uqi had second thoughts about the wisdom of this trip into the unknown.

He questioned Qillarsuaq’s leadership, something he had probably never done before. Then he turned back, taking at least 24 people with him. This occurred probably in 1861 or 1862.

Qillarsuaq continued north, leading the remainder of the party, eventually crossing from Pim Island, off the Ellesmere Island coast, to Anorituuq, Greenland, where they found abandoned habitations but no people.

Hunting as they moved southward, they established a temporary camp at Taserartalik near Etah. It was there, probably in 1863, that they encountered their first Inuk, Arrutak, a man who had lost a leg in an accident but carved himself a wooden limb that allowed him to get about quite well.

As this was the first Inuk they had seen, Qillarsuaq and his party believed that they had arrived in the land of the wooden-legged people. At Arrutak’s insistence, the newcomers moved their camp south to Pitorarvik, where a large group of Inuit were encamped for spring hunting.

Qillarsuaq’s quest was over. He had finally reached a land where he had no enemies. For the Inughuit, a time of desperation was also at an end.

They had met new people, speaking a language similar to their own, who were, in the words of Father Guy Mary-Roussilière, who documented this migration, “bringing with them knowledge which would help them in their battle for survival.”

A few American explorers had already encountered the Inughuit and had predicted the extinction of the tribe; its population numbered no more than 140. The newcomers brought new blood and new hunting technology, as well as their stories and folklore.

But it seems that trouble followed Qillarsuaq wherever he went. He had left both the Cumberland Sound area and later northern Baffin Island to distance himself from his enemies.

But even in far-off northern Greenland, he was destined not to find peace. He had a falling out with a powerful sorcerer who had befriended him shortly after his arrival in Greenland.

Believing that the man, Avatannguaq, was plotting against him, Qillarsuaq and two accomplices murdered his former friend. Soon after, Qillarsuaq’s health began to fail and he was overcome with a strong urge to see his homeland again before he died. Not all of his fellow migrants agreed.

Qillarsuaq and his followers had been in Greenland for six years when the aging shaman set out again on his final journey, westward toward Ellesmere Island from where he would continue south to Baffin Island.

Twenty or so people accompanied him. But the journey had only begun when Qillarsuaq died on the ice off Cape Herschel, twenty kilometres south of Cape Sabine, just off the Ellesmere coast. His followers buried his body at Cape Herschel, a point that the Inughuit have known since as Qillaqarvik.

The rest of the party traveled south to Makinson Inlet, where game and fish were scarce. Starvation, murder and cannibalism ensued. With their leader dead, two brothers concluded that there was no point continuing southward with the remainder of the treacherous party.

Merqusaaq and Qumangaapik, with three relatives, began the arduous journey back to the safety of Greenland. They reached Etah, probably in 1873. They remained, and many of the families of north-western Greenland today claim descent from the “allarsuit” — the “Canadian” migrants.

The story of Qillarsuaq and the migration that he led from Baffin Island to Greenland may be representative of countless undocumented migrations by which Inuit from the Bering Sea gradually populated the North American Arctic. Unlike the relocations of later days, in which whalers, traders and government moved Inuit from location to location to satisfy their own commercial and administrative purposes, Qillarsuaq’s story is unique in that his motives were his own.

His brief encounters with non-Inuit explorers and the sparse tracks he left in the historical record enable a rich picture of his and his followers’ exploits to be fashioned from a combination of non-Inuit history and Inuit oral accounts.

Thirty-year Canadian Arctic

resident Kenn Harper is a former grocer, teacher and

development officer. He is a businessman, historian,

researcher, blogger and writes his Taissumani

(Inuktitut for ‘long ago’) column in the weekly Nunatsiaq

News in print and online.

Thirty-year Canadian Arctic

resident Kenn Harper is a former grocer, teacher and

development officer. He is a businessman, historian,

researcher, blogger and writes his Taissumani

(Inuktitut for ‘long ago’) column in the weekly Nunatsiaq

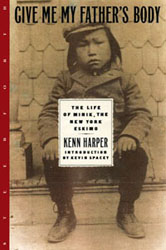

News in print and online.Harper is the author of Give Me My Father's Body, The Life of Minik, the New York Eskimo. It is the story of Minik Wallace, an Inughuit from northern Greenland who, along with his father and four others, was taken by explorer Robert Peary to live in a damp basement where they were studied like animal specimens and put on live display at the Museum of Natural History in New York City before all but Minik died of tuberculosis.

Harper lives in Nunavut’s capital, Iqaluit. He speaks fluent Inuktitut.

Ed: Qillarsuaq appears here with the generous permission of the author, Kenn Harper who wrote the story in two parts for his Taissumani columns in the July 8 and July 17, 2009 editions of Nunatsiaq News.

Read The Qitdlarssuaq Chronicles, parts 1-4, by Renee Wissink beginning in the December 2002 issue of The Fan Hitch.