In This Issue....

ISDI Launches New Partnership in Nunavik

Qimmiit Utirtut's First Litter

Update: Sledge Dog Memorial Fund

Recollections of the Doggy Man

Sledge Dogs of The Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, 1947-50

Video Reviews:

Secrets of Antarctica

Wolf Dog

Return of the Qimutsiit

Dogs That Changed the

World

Product Review: Leather Mittens by Sterling Glove

Navigating

This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index

of back issues by volume number

Search The

Fan Hitch

Articles

to download and print

Ordering

Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our

comprehensive list of resources

Talk

to The Fan

Hitch

The Fan Hitch

home page

ISDI

home page

Editor's/Publisher's Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Sledge Dogs Of The

Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey,

1947-50

by Raymond J. Adie

Introduction

The following notes are intended not as a

rigid set of

rules but as a guide for future Antarctic travellers:

common sense must

be used in their application. Systematic breeding,

training and driving

of dogs are essential in an organization as large as the

Falkland Islands

Dependencies Survey, but modifications must naturally be

made to suit particular

requirements.

Among the first members of the Survey, only

two - Captain

A. Taylor, R.C.E. (Port Lockroy, 1944-45 and Hope Bay,

1945-46) and Surgeon-Commander

E.W. Bingham, R.N. (Stonington Island, 1946-47) - had had

previous sledging

experience. With the exception of a few modifications

derived from Taylor's

experience, Bingham's technique of dog driving was

followed in later years

(Bingham, 1941).

All the sledge dogs originally used were brought from Labrador in 1944 and 1945 (Bingham, 1947a, p. 24, 31; James, 1947, p. 40). Few of these still remained in service in 1948 and 1949, but their progeny, born and bred in the Antarctic, proved larger in size and better-tempered than dogs brought from Labrador (James, 1947, p. 42).

Breeding

To obtain, and to retain in successive

generations, a

high standard of efficiency as a traction animal, sledge

dogs must be bred

with care. With very few exceptions domestic animals have

been improved

immensely by careful breeding through the centuries.

Animals possessing

special qualities, such as size, strength, milk yield and

colour, have

been constantly selected and mated with discrimination.

This preserves

and intensifies the genetic factors which, in good

environmental conditions,

produce in the mature animal whatever is specially valued.

Although sledge

dogs have been used domestically for many generations,

deliberate genetic

research has played little part in breeding. Further

improvement is probably

attainable in physical conformation, stamina, and

physiological efficiency.

In the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, where the

whole dog population

consists of not more than about 300 descendants of the few

dozen animals

originally imported from Labrador, conscious care in

breeding is essential

if efficiency is to be maintained. Continued breeding

within this small

population means that all the dogs must inevitably, after

a few generations,

be related to one another, leading to a concentration of

genetic qualities,

good or bad. So-called in-breeding, its popular meaning

being the close

and haphazard breeding within a small population, commonly

leads to general

deterioration. On the other hand, a very considerable

degree of breeding

between close relatives under proper control is the

standard method of

"fixing" in the breeding qualities of high value. Careful

breeding is thus

essential if the quality of the Falkland Islands

Dependencies Survey stock

of dogs is to be maintained, and the introduction of new

blood may be necessary

in the future. New blood, however, will not ensure high

quality unless

there is conscious discrimination.

The following traits are desirable in dogs

and bitches

selected for breeding: good physique and stamina; ability

to lead a team;

intelligence; good sense of direction; readiness to pull,

even under adverse

conditions; big feet and long, well-built legs; broad

chest and alert stance;

broad head and muzzle. Bitches selected should be good

mothers and capable

of suckling their pups without aid. Some dogs appear to

attain a good physical

condition while at the base but rapidly lose condition

while sledging.

It is therefore inadvisable to breed from them. It is

better to breed dogs

with short coats. At Hope Bay a particularly "shaggy"

strain resulted from

repeated and indiscriminate in-breeding of dogs with thick

woolly coats,

the length of the underwool or fur fibres being almost the

same as that

of the coarser guard hairs. Drift snow tends to adhere to

a "shaggy" coat,

so that a dog becomes encased in ice, or has large balls

of ice hanging

from its coat. At Hope Bay a dog had to be destroyed

because the excessive

weight of ice caused the skin on its back to tear,

exposing the flesh.

Several of the "shaggy" dogs at Hope Bay were subsequently

sheared like

sheep, but they still became "iced up".

To ensure that a bitch is served by a

particular dog,

both should be chained in close proximity during the heat

period of the

bitch. A bitch on heat in the field can cause chaos, and

at night should

be tethered separately some distance from the rest of the

team. At times

it is desirable that bitches should not be served, for

instance during

the first heat. For this purpose Bob Martin's "Antimate"

has been used

with some success.

Although sixty-eightl pups

were

born at Stonington Island in 1947-48, only three were kept

because

rearing entails much extra work, especially when the

majority of the staff

are absent from the base. For this reason it is considered

preferable to

breed pups at small stations, where more time is available

and food is

more plentiful. On the other hand, dogs bred at a sledging

base can be

trained at an early age to the ways of those who are to

drive them.

All pups born in the field were destroyed soon after birth. Whenever pups are not required they should be killed at the earliest opportunity, preferably within a few hours of birth. If bitches are allowed to suckle even a single pup for several days before it is destroyed, they invariably suffer from enlarged and inflamed mammary glands. This condition may cause abscesses which are difficult to cure, and keep a bitch out of her sledging team for an unnecessarily long period; occasionally it may even be necessary to destroy her. If the pups are taken away at birth, lactation ceases within two or three days, any milk being resorbed. In some cases bitches whose pups have been destroyed at birth retain condition and may be worked after a few days' rest. Others lose condition irrespective of whether they suckle a little or not.

Weaning

In 1948-49 thirteen pups were successfully

reared at Stonington

Island. The bitches were allowed to suckle them until the

beginning of

the third week. During this period the bitches' normal

ration was supplemented

with a special puppy mea1.2 Weaning then began,

first by introducing

the pups to Nestle's sweetened condensed milk mixed with

an equal quantity

of water. Within a week they drank from a saucer, but only

if they were

not allowed to feed from the mother. At this stage they

were fed four times

daily. Before the pups were fed in the morning the bitch

was chained apart

to prevent her suckling them during the day. After the

last feed of the

day the bitch was put back with the pups to keep them warm

during the night.

In the fourth and fifth weeks pups were fed twice daily on

a thin porridge-like

mixture of puppy meal enriched by condensed milk. The

condensed milk was

later omitted, and the food made a little thicker. The

bitch was taken

away from her pups after six to seven weeks. Feeding on

meal continued

until such time as the pups could eat minced seal meat and

liver without

difficulty.

Should a bitch be unable to suckle pups,

they may be reared

from birth on Nestle's sweetened condensed milk, mixed

with water in the

proportion of two parts to one. For this purpose a baby's

bottle and rubber

teat may be used.

In the first few weeks of weaning it is preferable to feed pups a little thrice daily rather than to overfeed them less frequently. Overfeeding may cause intestinal trouble (intussusception), which resulted in the death of three pups at Stonington Island. One meal a day is possible after eight to ten weeks. At this time it is desirable to provide water for the pups until they learn to eat snow.

Kennels and pens

Drift-proof canvas-covered kennels were

provided for bitches

with litters and for young pups being weaned. At night,

and during blizzards,

the entrances were covered with sacking to prevent

drifting snow from filling

the kennels and turning to ice on the floor.

Pup pens were made of netting-covered tubular frames, 4 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. Until the pups were three months old the pen was 4 ft. 6 in. high, but when they became more adventurous and began to climb out, the sections were turned on end to form a pen 6 ft. high. A kennel was built into one side of the pen.

Tethering

At the beginning of 1947 the majority of dogs

at Hope

Bay were roaming freely. During several months of freedom

they had formed

into groups, each with its own "king" dog. There was,

however, one "super-king"

dog acknowledged by minor "kings". There were endless

fights, and it soon

became necessary for a member of the party to be

constantly on watch to

prevent injuries. Eventually the dogs became unmanageable,

especially when

sledging began, and they had to be chained. Another reason

for doing this

was the danger that they would stray (James, 1947, p. 41).

A.R. Glen (1939, p. 185) prefers the use of

pens to that

of spans and chains. If there is relatively little

snowfall or drift, and

few dogs, this is a practical proposition, but at a base

like Hope Bay

where there were 134 dogs and pups in 1947, it was

impractical. The same

applies to Bingham's use of deadmen for tethering

(Bingham, 1947b, p. 44).

Tethering lines of steel wire cable (often

called spans)

to which 6 ft. dog chains were attached with bulldog grips

at intervals

of 15 to 18 ft., were used at Hope Bay and Stonington

Island in 1948 and

1949. All chains could be fitted with two swivels and a

swivel clip-hook,

to prevent tangling. Each cable, accommodating nine or ten

dogs (usually

a team), was 3/4 in. in diameter

and each end was

firmly picquetted. The cables were carefully inspected

from time to time

so that fraying could be prevented, or noticed before the

cable snapped.

Occasionally the nuts on a bulldog grip worked loose and

the friction of

a grip sliding along the cable led to rapid fraying. Pairs

of dogs often

came too close if the bulldog grip slipped, and fights

resulted. This trouble

was remedied by unlaying two strands of the cable and

inserting the bulldog

grip through the gap.

Before 1948, dogs at Stonington Island were

tethered to

deadmen buried in the snow at intervals of 15 to 20 ft.

Deadmen were also

used when a few dogs had to be tethered on sea ice during

winter. Disadvantages

are that a dog can easily pull them up in summer, and in

winter they are

difficult to dig out.

Light spans and chains have been suggested

for tethering

at night while sledging (Bird & Bird, 1939, p. 182).

They were used

by Hope Bay parties in 1946, but since 1947 the method

described below

has been used. Spans are cumbersome, and are unnecessary

when dogs are

well trained.

On the whole, the method of tethering

adopted at Hope

Bay and Stonington Island in 1948 and 1949 proved

satisfactory. The comments

of Bingham (1947b, p. 44) on the tethering methods used by

James (1947,

p. 43) were fully supported by later experience. A centre

trace formation

was generally used, the dogs were unharnessed and left

tethered to the

traces by their collars. Some dogs were picquetted

separately for a specific

reason. When fan trace formation was used the dogs were

tethered in threes

by tying three adjacent traces together with a slip knot,

and attaching

them to a picquet.

The use of ice-axes for picquetting (James,

1947, p. 43)

is wrong, and resulted in the breakage of twelve hafts in

two seasons at

one base alone. Steel angle-iron or spiral picquets are

much more efficient

and will hold a team without difficulty. In soft snow a

deadman, made from

a ration-box lid or a picquet laid horizontally, should be

used. A pair

of crampons, buried points downward, are equally

satisfactory.

If dogs are to be tethered, it is essential

to provide

a suitable collar for attaching the clip-hooks to the

chains. Clip-hooks

must be snapped on to the collar itself and never on to

the D-ring of the

collar. Constant pulling on the D-ring very soon ruins a

collar, especially

when dogs are tethered to cables at base for long periods.

Collars may

be of spliced cod-line or marline, flat leather, or a

round rope-core covered

with leather. Each type has a particular use. Unlike most

cheap leather

collars, neither cod-line or marline freeze in winter.

Strap leather collars

can easily be made if buckles and leather are available:

they must not

be too wide, or they will catch in the clip-hooks and wear

quickly in one

place. Strap leather collars were found most successful,

because they slide

easily round the neck, and neither tangle in the ruff nor

chafe the skin

under the throat. Round cross-section leather collars are

preferable but

they are too expensive. The kind of collar used is largely

a matter of

individual preference, but the use of choke collars is

inhumane.

Whenever possible, dogs should be tethered on

snow, because

this keeps them cleaner.

Harnesses

Harnesses used by the Falkland Islands

Dependencies Survey

are made up of 11 in. (flat measurement) tubular lampwick,

usually hand-sewn

with spun yarn. Single thickness 11 in. lampwick should

never be used,

as it stretches, cuts into the dog's coat, and chafes the

skin. Well-fitting

harnesses are essential for efficient hauling, and for

dogs of normal size

(of about 85 to 90 lb.) the measurements are shown in Fig.

2. If necessary

the measurements of A'B' and A'D' may be increased or

decreased by 1 in.

or, very occasionally, more. If a dog can easily slip out,

the harness

is at fault, generally because it fits badly under the

forelegs. Several

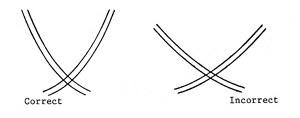

modifications to the original pattern (Fig. 1) may be

made: for instance,

the back straps (A'E') of the harness can be nipped at C';

the cross-piece

can be lengthened by increasing it from 6 to 8 in.: the

shoulder straps

(B'D') can be increased to 12 in. instead of the customary

10 to 11 in.,

and A'B' can be reduced from 13 to 7 in. The reduction in

length of the

shoulder strap and the corresponding increase in length of

the cross-piece

not only provides a better neck aperture but a more

comfortable fit on

the shoulders. This point is illustrated in Fig. 3, where

the original

and modified patterns of neck aperture are shown. The

cross formed by the

two shoulder straps should rest on the centre of the

chest, as shown in

Fig. 4.

Fig. 1. Lampwick dog harness. Pattern (after Bingham)

used by F.I.D.S.

in 1946.

Fig. 2. Lampwick dog harness. Pattern (as modified by

the author) used

by F.I.D.S. after 1947

(S.P.R.I. No 52/61/1). A'B', 7 in.; A'C', 7 in.; A'D',

19 in.; B'D',

12 in; C'E', 6 in; cross-piece, 8 1/2

in.

Fig. 3. Neck aperture.

Fig. 4. Shoulder straps.

Some dogs delight in extricating themselves

from harness,

however well-fitting it may be. To prevent this a small

loop-and-toggle

belly-band may be fitted at F' (Fig. 2).

If the dog's name is embroidered or inked on

the cross-piece,

identification is simple, and anyone who knows the dogs by

name can harness

the team. Coloured tags, until 1948 at Stonington Island,

were of little

value for this purpose because invariably the team driver

was the only

person who knew to which animal each particular harness

belonged. Lampwick

harnesses may freeze: the cross-threads of some types of

lampwick crack

and fray, leaving a tangled mass of longitudinal threads.

This can be prevented

by soaking in paraffin prior to use, a treatment which

does not harm the

dogs' skin.

As Glen (1939, p. 186) comments, dogs seldom chew harnesses and traces when they are well-fed and comfortable. As soon as they become very hungry, or entangled in the traces, they revert to chewing.

Traces

Although the method of driving and

consequently the type

of trace used should depend on surface conditions and the

nature of the

terrain, a driver usually prefers one particlar method and

type of trace,

which he must however be prepared to change with changing

conditons. Of

the two methods used at Stonington Island in the sledging

seasons from

1948 to 1950 - centre trace and paired fan3 -

the former was

used by every driver with great success, and was preferred

owing to its

simplicity.

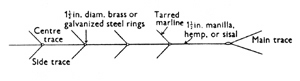

Fig. 5. Centre trace, with side traces and main

trace.

Centre trace. The centre trace was standard and accommodated nine dogs. Extensions to take two additional dogs could easily be added. The trace, made of 11 in. sisal rope4, comprised three sections 7ft. 6 in. long and one 9 ft. long, with 1 in. metal rings spliced between each section. Although galvanized steel rings were generally used, stout brass rings are preferable because they do not rust and wear the splices. The 9 ft. section had a 3 to 4 in. loop spliced in the end attached to the main trace. Reinforcement of this loop with a canvas sleeve prevented wear.

Fig. 6. Side traces as modified by the author (S.P.R.I.

No. 52/61/3.)

Side traces. The best length for

side traces is

between 2 ft. 3 in. and 2 ft. 6 in. Two types were used,

both made of tarred

marline.

The first type (Fig. 7) consisted of a loop

spliced at

each end of a suitable length of line, with a catspaw knot

attaching the

clip-hook to the side trace, and the side trace to the

ring of the centre

trace. The loop of the catspaw often slips over the

clip-hook swivel, preventing

it from working correctly, and may cause the trace to

unlay.

The second type (Fig. 6) is made of splicing a loop at one end of the line and a clip-hook at the other, care being taken not to make the clip-hook splice too small. The side trace is then attached to the centre trace by a catspaw knot.

Fig. 7. Side trace (S. P. R. I. No. 52/61/2).

If the loop at the clip-hook end of the side

trace wears

through, the trace can be shortened and the clip-hook

respliced. The length

of the leading dog's trace is determined by the team

driver according to

its habits.

On all sledge journeys spare traces, complete

with clip-hooks,

were carried to avoid delays when traces broke.

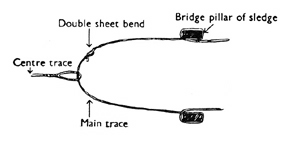

Main trace. With the exception mentioned below, each sledge was equipped with an ordinary one-piece main trace, to which the centre trace was attached by two adjacent karabiners. The karabiners, however, were found to wear both the main and the centre traces at attachment points. To prevent this a canvas sleeve was sewn over the main trace. Rubber hose has also been used for this purpose.

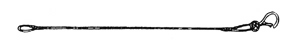

Fig. 8. Main trace (as modified by the author).

A modified type of main trace, made in two

parts (Fig.

8), proved easier to operate, even when iced-up. A loop

was spliced at

one end, and when the centre trace loop was slipped over

the other end,

a double sheet bend was tied; reknotting in a different

place each time

distributes wear evenly over attachment points.

A square toggle and loop, similar to that used by Bingham (1941, p. 79), can be used, but does not prevent continual wear at attachments.

Fan traces. Sets of paired fan

traces for seven,

nine and eleven dogs were available at Stonington Island,

and were used

for the greater part of the 1947-48 season, but hardly at

all in 1948-49

and 1949-50. The most suitable measurements for individual

traces were

two of 9 ft., two of 15 ft., two of 21 ft., two of 27 ft.,

and one of 33

ft.

The difference in length between pairs of traces is 6 ft., and a square-toggled extension trace is used for attaching them to the main trace. This type of extension (Bingham, 1941, p. 379) to the main trace is important, because it allows easy unravelling of the fan throughout the day without the possibility of dogs escaping.

Feeding

During the summer it was customary at base to

give each

dog approximately 4 lb. of seal meat without blubber every

alternate day.

Blubber was not given to dogs during the summer because it

always passes

straight through them, and invariably finds its way on to

their coats,

which become badly matted.

During the winter the dogs at base usually

received every

alternate day approximately 6 lb. of meat and blubber, of

which a third

was blubber. In 1948 very few seals were killed at

Stonington Island after

the beginning of March.5 The resulting shortage

of meat necessitated

the introduction of different forms of feeding. Blubber

which had been

saved during the late summer was cut into squares weighing

approximately

1 to 1 1/2 lb. One of these,

together with 2 lb. of

Bovril dog pemmican, constituted one meal. Because dogs

appear to need

oil or blubber, especially in winter, stock fish (dried

cod) was used together

with blubber as a meal on alternate days. Owing to the

limited quantities

of seal blubber and stock fish available at Stonington

Island in 1948,

pemmican alone was fed to the dogs for long periods. In

order to provide

some variety, it was finally decided to feed pemmican

daily for three days

followed by stock fish and blubber on the fourth day to

last two days.

Occasionally stock fish were fed together with 1 lb. of

pemmican on alternate

days.

On all sledge journeys the dogs were given 1

lb. of pemmican

a day. Double feeds were given whenever signs of fatigue

appeared. At Stonington

Island in 1948 it became the practice to reserve a small

stock of seal

meat, as a special contribution to the dogs' diet in the

ten days before

a winter sledging journey began; this provided four good

meals, which perhaps

helped the dogs to withstand the rigours of winter

sledging. Lack of stamina

during any particular winter journey may be accounted for

by poor feeding

prior to the start. While the dogs were away on such a

journey, a number

of seals were often killed in Neny Fjord, and on their

return to base the

dogs were given seal meat and blubber for several weeks

until the next

journey began. From the beginning of October until the

beginning of March

the following year they were fed on seal meat. This,

together with constant

exercise, made a great improvement in their general

condition.

The failure to revictual Stonington Island

in the summer

of 1948-49 caused a shortage of dog pemmican, and in 1949

precautions were

taken to ensure that the dogs would have an adequate

supply of seal blubber

throughout the winter. Again seal meat and blubber were

stored for feeding

the dogs before the winter journeys. No signs of any

dietary deficiencies

were observed in the ensuing winter.

As prolonged feeding on pemmican in the

field may be detrimental

to the dogs' health, it is desirable to give them seal

meat once or twice

every ten days, especially if heavy loads are being hauled

and the duration

of the journey exceeds thirty days. While sledging during

winter, dogs

were given more than 1 lb. of pemmican daily whenever

sufficient was available.

An extra 1/2 lb. of pemmican on

alternate days is

preferable, but it is usually difficult to carry the

additional load. K.S.P.

Butler did this on the main southern journey in 1947-48

down the west coast

of the Weddell Sea, and all his dogs returned to base in

excellent physical

condition after 105 days in the field.6 Butler

was able to give

his dogs 1 1/4 lb. of pemmican

daily because his party

had air support.

James (1947, p. 41) and Bingham (1941, p.

373) both advocate

hot meals for dogs at base in winter. Once again, this

depends upon the

number of dogs; with large numbers it is out of the

question, but for sick

dogs, or bitches with litters, it is certainly advisable.

In summer, when

snow is not available at the tethering place, dogs must be

given water

for drinking every day.

At Stonington Island in 1948 a total of 3260 lb. of pemmican was used for feeding at base in the winter, and approximately 5000 lb. during sledge journeys. In addition, fifteen bales of stock fish and some eighty seals were used at base. Similar quantities were consumed in 1949.

Training

Pups were accustomed to harness by walking

them round,

thus allowing them to exercise their natural instinct to

pull. The next

step was to run them in a quiet team, at first alongside a

bitch. Normally

a pup will pull with vigour, and within half an hour will

become completely

exhausted. Such training for ten successive days should

enable a pup to

take part in journeys. Stamina for pulling heavy loads

over great distances

for long periods develops only after a pup has been in the

field for several

months.

Pups can be trained to pull in any of the

standard formations,

but it was found most successful to use a centre trace

because when several

pups are pulling in paired fan formation chaos usually

results. Once discipline

has been instilled, training can continue using paired fan

traces. With

several older dogs in the leading positions, usually two

young dogs are

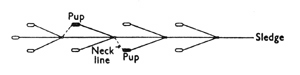

inspanned in the centre of the team (Fig. 9). An

additional neck line from

the pup's collar or shoulder straps to the centre trace

ring ahead generally

prevents the pup from dawdling, pulling out of harness

backwards, or otherwise

causing trouble. A belly-band (Fig. 2) may be used in

addition to the neck

line to prevent the pup from slipping out of the harness.

In training leaders, care should be taken to accustom the dog to a forward position in the team at an early stage; later the dog should be put up alongside the leader until such time as he will answer all commands and is proficient in leading. Then he may lead his own team.

Fig. 9. Centre trace formation, showing method of

pup-training.

The words of command used by the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey are corruptions from arctic terms. In order to standardize them the following terms were used at Stonington Island:

To start "UP DOGS, WEET"

To stop "A-a-a-a-"

Turn right "AUK, AUK" ("au" pronounced as "ou" in loud)

Turn left "I-r-r-re" (with a long rolling "r")

With well-trained teams it is unnecessary to repeat commands, unless turning right or left, when the command must be repeated until the dogs are heading in the required direction.

Acknowledgements

The writer gratefully acknowledges information about

dog-breeding contributed

by G.C.L. Bertram, and constructive criticism by B.B

Roberts and V.E. Fuchs.

References

BINGHAM, E.W. (1941). Sledging and sledge dogs. Polar

Record, Vol.

3, No. 21, p. 367-85.

BINGHAM, E.W. (1947a). The Falkland Islands Dependencies

Survey, 1946-47.

Polar Record, Vol. 5, Nos. 33/34, p. 27-39.

BINGHAM, E.W. (1947b). Comments on D. James's article on

the sledge

dogs of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, see

below. Polar Record,

Vol. 5, Nos. 33/34, p. 43-44.

BIRD, C.G. & Bird, E.G. (1939). The management of

sledge dogs.

Polar Record, Vol. 3, No. 18, p. 180-84.

GLEN, A.R. (1939). Comments on Messrs Bird's article on

the management

of sledge dogs, see above. Polar Record, Vol. 3, No. 18,

p. 184-87.

JAMES, DAVID (1947). The sledge dogs of the Falkland

Islands Dependencies

Survey, 1945-46. Polar Record, Vol. 5, Nos. 33/34, p.

40-43.

Postscript

The first draft of the article reprinted

above (by courtesy

of the Editor of The Polar Record) was written at

Stonington Island in

1949 as a "base report" on the state of the dog

population. In due time,

and after countless redrafts, it was published in 1952.

Many articles on

huskies and dog handling, both Arctic and Antarctic, had

previously appeared

in The Polar Record, and the idea behind the publication

of this article

was to reflect the dog-handling techniques current in the

Antarctic in

1950. David James had already written about the dogs used

by Operation

Tabarin, and Surgeon Commander E.W. Bingham had recorded

aspects of dog-handling

in the first days of the Falkland Islands Dependencies

Survey.

In the early years of FIDS there was total

reliance on

dogs for transport. All of the long reconnaissance

journeys were done by

dog sledge with virtually no support, except for a few

field depots. At

one time, to say you had been to the Antarctic was

tantamount to saying

you were an expert dog driver - far from the truth,

because there is much

more to successful dog-driving than meets the

inexperienced eye!

However, field-work techniques were

changing. The first

aircraft arrived in the Antarctic to support FIDS field

work and it was

not uncommon to see a two-man sledging unit, complete with

dogs, being

loaded aboard one of these aircraft. Then came the first

motor toboggans

which were initially used on an experimental basis until

their reliability

was thoroughly proven. Once field work had been fully

mechanized, the dogs

were slowly relegated to a back-up role and a small

breeding population

of about 40 dogs was maintained at Adelaide Island. This

decision precipitated

countless fierce arguments between the "pro-dog" and the

"pro-vehicle"

camps, and to this day, even in England, these same

arguments go on between

ex-Fids. This is still one of the main talking points at

BAS Club Reunions!

Times have changed; all of us must move with

advancing

technology, but for how much longer will the Survey's dog

population survive.

It is difficult to appreciate fully that 26 years have

passed since this

article was first drafted.

End Notes

1 Out of sixty of these pups (in eight cases

sex was not

identified before destruction) forty-five were males and

fifteen females.

2 "Casco Puppy Meal", a proprietary dog food,

was available

at Stonington Island.

3 "Paired fan" (trace lengths in pairs except

for single

leader) is a new term suggested for what has previously

been known by a

variety of terms such as "modified fan", "modified fan

hitch", "British

Graham Land Expedition method" or "Mackenzie River

method".

4 Sisal rope was used because neither manilla

nor hemp was

available. Manilla and hemp wear better and last much

longer than sisal.

5 No seals were brought from the Argentine

Islands in February

1948, because the John Biscoe was unable to make a second

run round the

Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey bases.

6 This period includes the ninety-nine days of

the main

journey and six days travel immediately preceding. Seal

meat was fed at

intervals throughout this period.