Defining

the Inuit Dog

Canis familiaris borealis

by Sue Hamilton

Canis familiaris borealis

by Sue Hamilton

© December 2011, The

Fan Hitch, all rights reserved

revised: December 2020

revised: December 2020

I.

Introduction

A.

The

Inuit Dog’s place in the natural world

B. The Inuit Dog is not a wolf!

C. Dangerous confusion

B. The Inuit Dog is not a wolf!

C. Dangerous confusion

A. The Name Controversy

B. Defining 'Purity'

C. Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

D. The Belyaev Experiment

E. Summary

B. Defining 'Purity'

C. Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

D. The Belyaev Experiment

E. Summary

A. Ancient

history

B. Recent history: The Inuit Dog in service to nations

B. Recent history: The Inuit Dog in service to nations

1. Exploration

2. War

3. Sovereignty

2. War

3. Sovereignty

C.

Population

decline

A. In the North

B. Below the tree line

B. Below the tree line

A.

Inherited

diseases

B. Disease prevention and access to veterinary services

B. Disease prevention and access to veterinary services

A.

Appearance

B. Behavior

C. Performance

D. The big picture

VII. The Inuit Dog in

Scientific Research, Films andB. Behavior

C. Performance

D. The big picture

in Print

VIII. Acknowledgements

Appendix 1: Partial list of scientific publications about

the Inuit Dog

Appendix 2: Selected (alphabetical) list of other resources

with a focus on Inuit Dogs

Appendix 3: A small sampling of other resources of

interest

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Defining the Inuit Dog

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

About The Fan Hitch

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor-in-Chief: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch,

Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published

four times a year. It is available at no

cost online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Copper Eskimo family travelling with dog sled, Coronation Gulf,

Northwest Territories (Nunavut); photographed during the 1913-1918

Canadian Arctic Expedition lead by Vilhjalmur Stefansson.

Photo: R.M.Anderson; archived as #20288 in the Canadian Museum of History

III. History

A. Ancient history

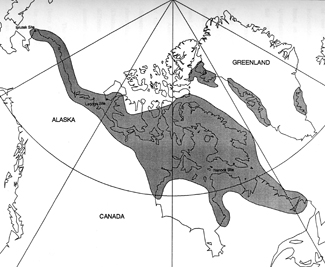

Inuit Migration from Alaska across Canada to Greenland

The earliest evidence

of domestic dogs in North America dates to ~10,000

years ago. Until recently, not much was known about

how, when, and if domestic dogs were introduced to

North America, or if they were domesticated from

North American wolves. Ancient DNA and

archaeological data from a 2018 study (Leathlobhair

et al. 2018) suggests that North American

pre-contact dogs (PCD) belonged to a now extinct

lineage, are most closely related to ancient

Siberian populations, and did not derive from North

American wolves. This data suggests that pre-contact

dogs were introduced to the Americas by people from

Siberia/Beringia, and subsequently went extinct

after the introduction of European breeds.

Interestingly, this now extinct lineage of

pre-contact dogs appears to be closely related to

Arctic breeds (Malamutes and Siberian Huskies),

however, PCD are not the direct ancestor of these

modern breeds. This leads to questions about the

origin of Arctic breeds, both modern and ancient.

The North American Arctic was initially colonized by two waves of humans, and their dogs. The first, the Paleo-Inuit, who arrived in the North American Arctic roughly 4,500 years ago from Siberia, and show little evidence for extensive use of dogs. The second wave occurred ~2,000 years ago, with the arrival of the Thule people (ancestors of the Inuit), who heavily utilized dogs for sled traction. The Thule/Inuit culture brought a unique toolkit with it to North America, including the development and widespread usage of the umiak and kayak for sea travel, and the dog sledge for use on land and ice (Mathiassen, 1927; McGhee, 1996; Gulløv HC. 1997). The Thule people translocated this culture out of Alaska eastward to Greenland, and along the coast of subarctic Eastern Canada starting in 1000 BP (McGhee, 2009; Friesen and Arnold, 2008). The rapid expansion of the Inuit is attributed in part to their exploitation of advanced transportation technologies.

Until recently, it had been unclear what the relationship between Paleo-Inuit and Thule dogs, and pre-contact dogs was. Genetic evidence from ancient archaeological dog remains (Ameen, Feuerborn, Brown, Linderholm et al. 2019), suggests that ancient Paleo-Inuit dogs largely shared the same genetic signature as pre-contact dogs. However, the Thule/Inuit dogs did not possess the pre-contact dog and Paleo-Inuit genetic profile. The ancient Thule/Inuit dogs harbored another genetic signature, which was common in ancient Siberian samples, and did not derive from the Paleo-Inuit dogs. Additionally, (Ameen, Feuerborn, Brown, Linderholm et al. 2019) performed morphometric analysis (Geometric Morphometrics; GMM) on mandibles and crania from these specimens. They found that Thule/Inuit dogs tended to be larger, with a more narrow cranium than Paleo-Inuit dogs, suggesting that these populations are morphologically different, supporting the genetic data.

One must not assume the Inuit Sled Dog to be only the aboriginal sledge dog of the circumpolar north based on its name alone, for it possessed other essential skills as well. Many characteristics: scent locating seal breathing holes (aglu) and birthing lairs, tracking and catching prey wounded by hunters, alerting hunters and family encampments to the presence of bears and then keeping these large predators at bay, carrying belongings on their backs in summer and hauling a heavily laden qamutiq (sledge) over snow and ice covered surfaces, used for clothing (wolves as well) and occasionally as food either preferentially, or during periods of famine (Mason-Maclean, McManus-Fry, and Britton, 2019; Ameen, Feuerborn, Brown, Linderholm et al. 2019), along with their legendary resilience to hardships, have credited the Inuit Dog as being the principal reason for the survival of the ancestors of today’s modern Inuit1 This influence has continued into the mid-twentieth century, at which time the lives of these hunters, already affected by the presence of the outside world, began to dramatically change.

Literature Cited:

Ameen, Carly, Tatiana R. Feuerborn, Sarah K. Brown, Anna Linderholm, Ardern Hulme-Beaman, Ophélie Lebrasseur, Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding et al. "Specialized sledge dogs accompanied Inuit dispersal across the North American Arctic." Proceedings of the Royal Society B 286, no. 1916 (2019): 20191929.

Brown, Sarah K., Christyann M. Darwent, and Benjamin N. Sacks. "Ancient DNA evidence for genetic continuity in arctic dogs." Journal of Archaeological Science 40, no. 2 (2013): 1279-1288.

Leathlobhair, Máire Ní, Angela R. Perri, Evan K. Irving-Pease, Kelsey E. Witt, Anna Linderholm, James Haile, Ophelie Lebrasseur et al. "The evolutionary history of dogs in the Americas."

Science 361, no. 6397 (2018): 81-85.

Masson-Maclean E, McManus-Fry E, Britton K. 2019. The archaeology of dogs at the pre-contact Yup’ik site of Nunalleq, Western Alaska. In Beyond domestication: archaeological investigations into the human-canine connection (eds A Burtt, B Bethke).Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press

McGhee R. 2009. When and why did the Inuit move to the eastern Arctic. In The Northern World, AD900–1400 (eds Herbert Maschner, Owen Mason),pp. 155–164. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Friesen TM, Arnold CD. 2008. The timing of the Thule migration: new dates from the Western Canadian Arctic

Mathiassen T. 1927 Archaeology of the central Eskimos: the Thule culture and its position within the Eskimo culture. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–24. Copenhagen, Denmark: Gyldendaslke Boghandel.

McGhee R. 1996 Ancient people of the Arctic. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

Gulløv HC. 1997 From middle ages to colonial times: archaeological and ethnohistorical studies of the Thule Culture in South West Greenland 1300–1800 AD. Copenhagen, Denmark: Dansk Polar Center.

The North American Arctic was initially colonized by two waves of humans, and their dogs. The first, the Paleo-Inuit, who arrived in the North American Arctic roughly 4,500 years ago from Siberia, and show little evidence for extensive use of dogs. The second wave occurred ~2,000 years ago, with the arrival of the Thule people (ancestors of the Inuit), who heavily utilized dogs for sled traction. The Thule/Inuit culture brought a unique toolkit with it to North America, including the development and widespread usage of the umiak and kayak for sea travel, and the dog sledge for use on land and ice (Mathiassen, 1927; McGhee, 1996; Gulløv HC. 1997). The Thule people translocated this culture out of Alaska eastward to Greenland, and along the coast of subarctic Eastern Canada starting in 1000 BP (McGhee, 2009; Friesen and Arnold, 2008). The rapid expansion of the Inuit is attributed in part to their exploitation of advanced transportation technologies.

Until recently, it had been unclear what the relationship between Paleo-Inuit and Thule dogs, and pre-contact dogs was. Genetic evidence from ancient archaeological dog remains (Ameen, Feuerborn, Brown, Linderholm et al. 2019), suggests that ancient Paleo-Inuit dogs largely shared the same genetic signature as pre-contact dogs. However, the Thule/Inuit dogs did not possess the pre-contact dog and Paleo-Inuit genetic profile. The ancient Thule/Inuit dogs harbored another genetic signature, which was common in ancient Siberian samples, and did not derive from the Paleo-Inuit dogs. Additionally, (Ameen, Feuerborn, Brown, Linderholm et al. 2019) performed morphometric analysis (Geometric Morphometrics; GMM) on mandibles and crania from these specimens. They found that Thule/Inuit dogs tended to be larger, with a more narrow cranium than Paleo-Inuit dogs, suggesting that these populations are morphologically different, supporting the genetic data.

One must not assume the Inuit Sled Dog to be only the aboriginal sledge dog of the circumpolar north based on its name alone, for it possessed other essential skills as well. Many characteristics: scent locating seal breathing holes (aglu) and birthing lairs, tracking and catching prey wounded by hunters, alerting hunters and family encampments to the presence of bears and then keeping these large predators at bay, carrying belongings on their backs in summer and hauling a heavily laden qamutiq (sledge) over snow and ice covered surfaces, used for clothing (wolves as well) and occasionally as food either preferentially, or during periods of famine (Mason-Maclean, McManus-Fry, and Britton, 2019; Ameen, Feuerborn, Brown, Linderholm et al. 2019), along with their legendary resilience to hardships, have credited the Inuit Dog as being the principal reason for the survival of the ancestors of today’s modern Inuit1 This influence has continued into the mid-twentieth century, at which time the lives of these hunters, already affected by the presence of the outside world, began to dramatically change.

Literature Cited:

Ameen, Carly, Tatiana R. Feuerborn, Sarah K. Brown, Anna Linderholm, Ardern Hulme-Beaman, Ophélie Lebrasseur, Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding et al. "Specialized sledge dogs accompanied Inuit dispersal across the North American Arctic." Proceedings of the Royal Society B 286, no. 1916 (2019): 20191929.

Brown, Sarah K., Christyann M. Darwent, and Benjamin N. Sacks. "Ancient DNA evidence for genetic continuity in arctic dogs." Journal of Archaeological Science 40, no. 2 (2013): 1279-1288.

Leathlobhair, Máire Ní, Angela R. Perri, Evan K. Irving-Pease, Kelsey E. Witt, Anna Linderholm, James Haile, Ophelie Lebrasseur et al. "The evolutionary history of dogs in the Americas."

Science 361, no. 6397 (2018): 81-85.

Masson-Maclean E, McManus-Fry E, Britton K. 2019. The archaeology of dogs at the pre-contact Yup’ik site of Nunalleq, Western Alaska. In Beyond domestication: archaeological investigations into the human-canine connection (eds A Burtt, B Bethke).Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press

McGhee R. 2009. When and why did the Inuit move to the eastern Arctic. In The Northern World, AD900–1400 (eds Herbert Maschner, Owen Mason),pp. 155–164. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Friesen TM, Arnold CD. 2008. The timing of the Thule migration: new dates from the Western Canadian Arctic

Mathiassen T. 1927 Archaeology of the central Eskimos: the Thule culture and its position within the Eskimo culture. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–24. Copenhagen, Denmark: Gyldendaslke Boghandel.

McGhee R. 1996 Ancient people of the Arctic. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

Gulløv HC. 1997 From middle ages to colonial times: archaeological and ethnohistorical studies of the Thule Culture in South West Greenland 1300–1800 AD. Copenhagen, Denmark: Dansk Polar Center.

Ed: The Fan

Hitch is indebted to evolutionary biologist

Sarah K. Brown, PhD for her contribution to

III. A. Ancient History of the Inuit Dog

Sarah K. Brown, PhD for her contribution to

III. A. Ancient History of the Inuit Dog

Looking for seal pups in a birthing lair

Photo: Doug E. Wilkinson; N-1979-05 /NWT archives;

courtesy of the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre

1. Exploration

Arctic

explorers

came to the North eager to gain notoriety and

favor by mapping, naming and claiming arctic

territory for their homeland’s sovereigns. They

also sought to find the fabled Northwest

Passage. Others searched for fame as the first

to reach the geographic North Pole.

Missionaries, as well, came to establish their

religious domination. Fur traders, seeking their

own version of fortune for themselves and the

companies they represented established trading

posts to encourage Inuit to bring in as many fox

and other pelts as could be trapped. It was

through these foreigners, who traveled by dog

team, that the legendary strength and endurance

of the Inuit Sled Dog was made known to the

outside world.

The Hobbits, a

British Antarctic Survey dog team, sledging on sea ice

Painting by Mike Skidmore

Painting by Mike Skidmore

When

polar exploration headed south, the Inuit Dog's

reputation made it the choice (although not exclusive to

every expedition or nationality) of Australia, New

Zealand, France and Great Britain who established

Antarctic bases in the early 20th century. Beginning in

the 1940s, the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey

(FIDS), now called the British Antarctic Survey (BAS),

began the golden era of Antarctic exploration and

scientific discovery. Much of the early knowledge

gained, still invaluable to this day, was made possible

thanks to the endurance and stamina of "British

Antarctic Huskies" – Inuit Sled Dogs2.

Due to political maneuvering associated with the Madrid Protocol, all non-indigenous life (except human) was banned from the continent as of April 1994. Save for a very few BAS huskies that were "repatriated" to their homeland in Arctic Quebec (Nunavik), the British government ordered the doggy men, many of whom who owed their lives to the dogs, to shoot these loyal companions. The remorse and bitterness over this act has not lessened over time. Nearly fifty years since some of these "Fids", as they are still nostalgically called, sledged across the continent, they still show fierce loyalty and respect for their dogs.3 The British Antarctic Husky Memorial was created to honor these dogs so that their contributions will never be forgotten.

Sadly, the dogs returned to Arctic Quebec died and no animals can be traced back to the BAS dogs, thus losing a valuable and unique genetic population of Inuit Sled Dogs. However, frozen semen from one of the dogs returned to Canada was collected and stored in a sperm bank.4

Due to political maneuvering associated with the Madrid Protocol, all non-indigenous life (except human) was banned from the continent as of April 1994. Save for a very few BAS huskies that were "repatriated" to their homeland in Arctic Quebec (Nunavik), the British government ordered the doggy men, many of whom who owed their lives to the dogs, to shoot these loyal companions. The remorse and bitterness over this act has not lessened over time. Nearly fifty years since some of these "Fids", as they are still nostalgically called, sledged across the continent, they still show fierce loyalty and respect for their dogs.3 The British Antarctic Husky Memorial was created to honor these dogs so that their contributions will never be forgotten.

Sadly, the dogs returned to Arctic Quebec died and no animals can be traced back to the BAS dogs, thus losing a valuable and unique genetic population of Inuit Sled Dogs. However, frozen semen from one of the dogs returned to Canada was collected and stored in a sperm bank.4

2. War

The

original establishment of a British presence in Antarctica

was part of the wartime (WWII) effort, Operation Tabarin.

But Inuit Dogs were "recruited" with plans to use them in

Europe as well. In his article, Sled

Dogs in His Majesty's Service: Clark's Eskimo Dogs in

World War II, Charles L. Dean, author of Soldiers and Sled Dogs: A

History of Military Mushing, describes how

in 1942 the British military arranged for the purchase of

Inuit Dogs from Ed Clark of Lincoln, New Hampshire. These

dogs were sent to both Iceland and Scotland, destined to

work in Norway.

3. Sovereignty

In

post-war Greenland, with the cold

war heating up, the Danish

government established a secret

military sledge dog patrol, code

name "Operation Resolute". Three

years later the program was

revealed to the public as the now

famous Sirius Patrol. Today, from

their headquarters in Daneborg on

Greenland's east coast, the only military dog sledge

patrol in the world sends

out five teams of two Danish

soldiers and eleven dogs traveling

the huge expanse of north and

northeast Greenland surveilling

Danish sovereignty, conducting

military exercises and serving as

the civilian police authority.

During a typical year,

collectively the teams may cover

over 11,000

mi (18,000 km).

Sirius Patrol dog man Peter Schmidt Mikkelsen and

his team, from 1000 Days with Sirius by P. Mikkelsen,

Photo: Peter Schmidt Mikkelsen

In April 2010, a Sirius

Patrol team was invited to participate in OP Nunalivut 10,

a joint operation by the Canadian Forces in Canada's

North. It utilizes the unique capabilities of the Canadian

Rangers in support of Joint Task Force North (JTFN)

operations in the extreme environment of the high Arctic.

In an interview at the conclusion of the joint

Canadian/Danish exercise, published in the June

2010 issue of The Fan Hitch Journal Captain

Neal Whitman, Deputy Commander of 1 Canadian Ranger Patrol

Group, stated that the Canadian military had no plans to

specifically form a Sirius Patrol-like division. "There

is a very unique capability that works very well for the

Danish concept of operations where they're patrolling

along the north eastern coast of Greenland in a very

isolated environment," Whitman explained. "In

our context it gets a little bit different though

because our area of operations is a lot more heavily

populated really than the areas that the Sirius Patrol

operates in. We operate directly with the aboriginal

communities. Fifty-eight different communities

participate in the [annual] program and a total of

sixteen hundred Rangers, which is quite different from

the twelve that participate in the Sirius Patrol. For

our purposes, again we just choose whatever the

community wants to use to get out on the land. If they

want to use dog sleds then we can support that and if

they want to use snowmachines we can support that. So

for us it's really tied in to what the community wants

to do and what they feel is the way to get around."

C. The population decline

There is no doubt that the numbers of traditional Inuit Dogs working in the Canadian North5 has dwindled precipitously in the last century, leading to Bill Carpenter and John McGrath's efforts to restore their numbers with their creation of the Eskimo Dog Recovery Project (see II B). Some of these reasons were:

C. The population decline

There is no doubt that the numbers of traditional Inuit Dogs working in the Canadian North5 has dwindled precipitously in the last century, leading to Bill Carpenter and John McGrath's efforts to restore their numbers with their creation of the Eskimo Dog Recovery Project (see II B). Some of these reasons were:

- genetic contamination by non-indigenous dogs brought north by explorers, missionaries, prospectors, fur traders and other workers;

- diseases introduced by southern dogs to disease-naive aboriginal dogs;

- population decline as a result of a hunting society relocating into settlements, which accelerated beginning in the 1950s;

- arrival of the snowmachine (although many Inuit wives still admit that they don't worry when their husbands go out hunting by dog team, but they do when snowmobiles are used. A dog team will not break down; they can find their way in a blizzard; they can help with the hunt; and they have a sense when the sea ice is dangerously thin);

- Surely the most controversial and contentious issue involving the decline of traditional working teams of Inuit Sled Dogs is what is commonly referred to as the slaughter of sled dogs by the RCMP and others said to have taken place from the 1950s to the 1970s. A year-long self-examination by the RCMP concluded in 2006 that some dogs were killed to end their suffering from sickness and for human safety reasons. However, investigations by both the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (Nunavut) and Makivik (Nunavik) truth commissions' investigations, concluded in 2010, have determined otherwise and described far more complex issues leading to the killing of sled dogs as well as other cultural-social injustices.6

Challenges to a vibrant

northern population of traditional Inuit Dogs continue

with:

- influences of a wage-earning economy and lifestyle;

- loss of Elders to teach traditional ways;

- lack of access to vaccines and veterinary care.

Elder Paloosie Koonaloosie was a traditional and very well

respected hunter from Qikiqtarjuaq, Nunavut. After he died,

none of his children wished to continue on with their father's

way of life. Photo: Kevin Slater, Mahoosuc Guide Service

The presence of non-indigenous dogs is now ubiquitous throughout the Canadian North and currently there are no regulatory mechanisms in place to control this influx, either by outright banning or by allowing only altered dogs to accompany their owners north. In Greenland there is a law forbidding non-indigenous breeds into regions where sled dogs are kept as a measure to keep the Greenland Inuit Dog uncontaminated. However it is believed that strict enforcement has not been in place. For example, after a 1986 distemper epidemic, traditional Inuit Dogs from the north Baffin region of Canada were sent into the Thule District of Greenland. Dogs were also sent into this region from other parts of Greenland as well.7

1 The Inuit Dog: Its Provenance, Environment and History; Ian Kenneth MacRury; pg 45, para. 1.

2 See The Contribution of Dogs to Exploration in Antarctica by Peter Gibbs, The Fan Hitch, V5N2, March 2003.

3 Two of the many examples found throughout The Fan Hitch are: How do you say good-bye? by Peter Noble; V10, N4, September 2008 and Brave Little Heart by Ken Pawson, V2 N2, November 1999.

4 Personal communication, Winter 2009.

5 Although it is apparent that there are still authentic Inuit Dogs in Greenland, the status of that population is not clearly known to this author.

6 The RCMP, Qikiqtani Truth Commission and Makivik official reports can be found under "Official reports regarding Canadian Federal Government vis-a-vis Inuit social/cultural issues, including sled dogs" on The Fan Hitch Resources page.

7 Personal communications with people of the Baffin region.