Defining

the Inuit Dog

Canis familiaris borealis

by Sue Hamilton

© December 2011, The Fan Hitch, all rights reserved

revised: December 2020

Canis familiaris borealis

by Sue Hamilton

© December 2011, The Fan Hitch, all rights reserved

revised: December 2020

A.

The Inuit Dog’s place in the natural world

B. The Inuit Dog is not a wolf!

C. Dangerous confusion

B. The Inuit Dog is not a wolf!

C. Dangerous confusion

A. The Name Controversy

B. Defining 'Purity'

C. Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

D. The Belyaev Experiment

E. Summary

B. Defining 'Purity'

C. Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

D. The Belyaev Experiment

E. Summary

A. Ancient

history

B. Recent history: The Inuit Dog in service to nations

B. Recent history: The Inuit Dog in service to nations

1. Exploration

2. War

3. Sovereignty

2. War

3. Sovereignty

C.

Population decline

A. In the North

B. Below the tree line

B. Below the tree line

A.

Inherited diseases

B. Disease prevention and access to veterinary services

B. Disease prevention and access to veterinary services

A.

Appearance

B. Behavior

C. Performance

D. The big picture

VII. The Inuit Dog in

Scientific Research, Films andB. Behavior

C. Performance

D. The big picture

in Print

VIII. Acknowledgements

Appendix 1: Partial list of scientific publications about

the Inuit Dog

Appendix 2: Selected (alphabetical) list of other resources

with a focus on Inuit Dogs

Appendix 3: A small sampling of other resources of

interest

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Defining the Inuit Dog

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

About The Fan Hitch

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor-in-Chief: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch,

Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published

four times a year. It is available at no

cost online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Inuit Dogs from the Thule District of Northwest Greenland

Photo: Tsgt. Dan Rea, USAF

IV. The Inuit Dog in the

21st Century

A. In the North

Despite all that has taken place in the past couple of hundred or so years, and the current socio-economic challenges that continue to keep the future of the traditional Inuit Dog uncertain, this aboriginal dog endures in regions of arctic Canada and northern and eastern districts of Greenland. (While it is largely gone from Alaska and the western Canadian Arctic in the aboriginal use sense, the Inuit Dog exists there to some degree for recreational sledding and tourism). There is some evidence that there may exist (or did exist) Russian "precursors” to Inuit Dogs.

A Russian hunting with his dog, 1960.

From Dogs, published by Barbara Woodhouse

Photograph by Bavaria Verlag.

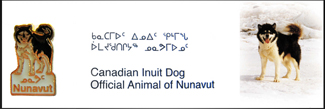

In May 2000 the year-old government of Nunavut honored the Inuit Dog – not the seal, caribou, musk ox or even the polar bear - as its official territorial animal. The choice recognizes the Inuit Dog as being uniquely responsible for the survival of the ancestors of today’s Inuit.

Ken MacRury's dog Ruff (r) was the Inuit Dog model

for Nunavut's official mammal.

Yet despite this recognition, and despite Inuit organizations investing time, effort and money in truth and reconciliation commissions, seeking solace for Elders who remember being left with no means to return to their hunting lifestyle after their dogs were shot; and despite recognizing the role dog teams have in tourism and sport hunting income,there appears to have been a general disconnect between interest in the Inuit Dog’s past and lack of vision to secure its future, with no centralized effort or expressed will to assure the future of this cultural icon. It may not be the role of northern governments to assume all the responsibility for preventing the extinction of such a significant part of their heritage. This belongs to individual northerners and concerned others who care deeply. however, there surely is a role for leadership to play, and not just one where communities hammer out laws further restricting the keeping of traditional dogs.

It has only been within the last decade that activities and programs focusing on the Inuit Sled Dog have come into being.

The QIMMEQ Project was born around 2014 as a “multidisciplinary project dealing with the cultural history of the [Greenland] dog, its origins and its health.” A sense of urgency recognized many pressures resulting in a regression in the traditional use of Greenland Dogs and their alarming population decline, down by 50% over the past thirty years. A diverse international team, but based at Ilisimatusarfik (the University of Greenland in Nuuk), the QIMMEQ Project established a set of goals, including social/cultural and scientific research, engaging the input from traditional Greenland (and elsewhere) dog teamers, setting an example for future endeavors and producing and sharing the bounties of the QIMMEQ Project’s labors which include many scientific papers, two conferences, a five episode documentary and a book.

With the establishment of the Nunavik and Nunavut Truth Commissions, much valuable history about the traditional use of dogs has been documented in the process of acquiring Elders testimonies describing the 19050-1970 period. Official Canadian federal government apologies have been accompanied by financial settlements, portions of which have been allocated for sled dog related issues. As recently as October 2020 the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, using some of the $2.9 million settlement dollars, has established a Qimmiit Revitalization Project.

Today few Inuit can follow in the footsteps of their Elders and live a traditional lifestyle using dogs. However, many Inuit feel strongly about their culture and, along with a few very dedicated non-Inuit, keep and use dogs. And so traditional Inuit Dogs can still be found in their native habitat of arctic Canada and Greenland still used for harvesting country food for people and dogs, as well as sport hunting, eco-tourism and expedition travel.

Traveling on qamutiit (sledges) and with dogs harnessed in the traditional fan hitch formation, events such as the Nunavut Quest in the Baffin region and Ivakkak in Nunavik are popular "races". They should not be confused with events like the Iditarod. The logistics and goals are different. While strictly speaking participation and support does not specifically encourage the breeding, keeping and continued use of the traditional Inuit Dog, these events are significant in that they do promote the culture of dog team travel, paying homage to Elders who remember their past living on the land, while stimulating keen interest in the younger generation in whose hands the future of the Inuit Dog rests. It appears that grass roots efforts are springing up among both individuals and communities. Sometimes working together, and with enormous dedication, effort, sacrifice and little government support, dog team owners, Elders and cultural organizations, such as Clyde River, Nunavut’s Ilisaqsivik Qimmivut Program, are reaffirming/teaching Inuit values, which in one way or another can all be linked to the traditional uses of dog teams, to younger Inuit as well to tourists and other visitors seeking an eco/cultural experience.

Driving dogs west central Greenland.

photo: Hamilton

This caribou will feed humans and dogs.

photo: Hamilton

From Iqaluit up the east coast of Baffin Island

to Pond Inlet, Nunavut, 2009.

photo: Lynn Peplinski

Unlike cultured breeds of "working" dogs (sled dogs, hunting dogs, herding dogs) that have been incorporated into an all-breed kennel club registry program and bred to a written show dog breed standard, the Inuit Dog can be found outside of the arctic in both North America and Europe maintained and selected for reproduction based on its toughness and the ability to prove its working heritage. These dogs are used on recreational teams as well as multiple teams maintained by tourism outfitters and polar adventurers.

Ludovic Pirani's team takes a break on a trail

in Ontario, Canada. photo: Pirani

Femundsmarka National Park, Norway, April 2020. Eight dogs,

four in my team, two each in my daughters’ teams. Sleds

all loaded with enough food and gear for a week of

back-country sledding. Photo: Gisle Uren

Experts in canine landraces of Africa, Johan and Edith Gallant stated, "A landrace becomes a breed the moment it is taken out of his natural environment or niche and is then selectively bred towards a certain breed standard and/or purpose which differs from its ancestral background. A breed could eventually stay a landrace, if the breeders would go back regularly and get some dogs from where they originated."1

In addition to the periodic infusion of arctic-bred and proven aboriginal genes into below-the-treeline stock, Ken MacRury advises that extra attention must be paid to selection of dogs to be bred in light of what new undesirable "expressions" may manifest without the benefit of the rigors of a polar climate and lifestyle. 2 This includes diagnostic testing for inherited diseases and de-sexing dogs that have a poor work ethic or temperament not suited or appropriate for future generations. This is confirmed by Ginsburg's explanation of the role of buffering genes [II B] and how the Inuit Dog below the tree line may loose its standing as an aboriginal dog outside of its "native habitat".

1 "Breed, Landrace and Purity: What do they mean?" by Johan and Edith Gallant, The Fan Hitch, V13 N1; December 2010

2 Personal communication and comment in the September 2003 issue of The Fan Hitch, V5 N4 in his Featured Inuit Dog Owner, Part 2 interview