Defining

the Inuit Dog

Canis familiaris borealis

by Sue Hamilton

Canis familiaris borealis

by Sue Hamilton

© December 2011, The

Fan Hitch, all rights reserved

revised: December 2020

revised: December 2020

A.

The Inuit Dog’s place in the natural world

B. The Inuit Dog is not a wolf!

C. Dangerous confusion

B. The Inuit Dog is not a wolf!

C. Dangerous confusion

A. The Name Controversy

B. Defining 'Purity'

C. Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

D. The Belyaev Experiment

E. Summary

B. Defining 'Purity'

C. Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

D. The Belyaev Experiment

E. Summary

A. Ancient

history

B. Recent history: The Inuit Dog in service to nations

B. Recent history: The Inuit Dog in service to nations

1. Exploration

2. War

3. Sovereignty

2. War

3. Sovereignty

C.

Population decline

A. In the North

B. Below the tree line

B. Below the tree line

A.

Inherited diseases

B. Disease prevention and access to veterinary services

B. Disease prevention and access to veterinary services

A.

Appearance

B. Behavior

C. Performance

D. The big picture

VII. The Inuit Dog in

Scientific Research, Films andB. Behavior

C. Performance

D. The big picture

in Print

VIII. Acknowledgements

Appendix 1: Partial list of scientific publications about

the Inuit Dog

Appendix 2: Selected (alphabetical) list of other resources

with a focus on Inuit Dogs

Appendix 3: A small sampling of other resources of

interest

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Defining the Inuit Dog

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

About The Fan Hitch

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor-in-Chief: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch,

Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published

four times a year. It is available at no

cost online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

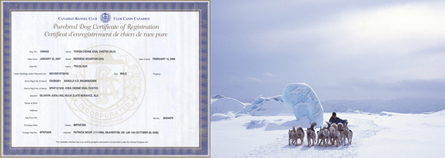

Although he lives below the tree line, sledding through the Skarvheimen Mountains

of Norway still offers Gisle Uren and his Greenland Dogs a polar landscape perfect

for arctic expedition training.

Photo: Jens Otto Nørbech-Eidem

II. Nomenclature,

Genetics and Identity

A. The name controversy

There is confusion regarding

terminology. Questions often asked are, “What is the

difference between a Canadian Inuit Dog and a Canadian

Eskimo Dog (CED)?” “Are they different from a Greenland

Dog?” “What is an Inuit Sled Dog?”

The name "Eskimo" is a corruption of a name assigned by non-Inuit more than a century ago. It has long since been considered pejorative, and the name was almost entirely abandoned at the time of the first Inuit Circumpolar Conference held in Barrow, Alaska in 1977 when "Inuit", meaning The People, was officially adopted. Honoring the desire to be identified as "Inuit" is not an issue of political correctness, but a matter of respecting the wishes of those who prefer to be called by a name of their own choosing, not one assigned to them by another culture. However, the term "Eskimo" is still used in an historic sense. And it is appropriate to identify Alaskan Yupik/Aleut as "Eskimo". The word is also used in the world of cultured all breed kennel club registered dogs, including the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC) who registers both the CED and the Greenland Dog (The CKC offers a massively confusing description of the Greenland Dog as follows: “Since the Inuit people of Canada’s Arctic were known to have emigrated from Greenland many centuries ago bringing their sled dogs with them, it’s possible this hardy polar Spitz breed is the forerunner of our native Canadian Eskimo Dog.”), The Kennel Club (Great Britain) who registers separately a CED and a Greenland Dog (calling it native to Greenland), and the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) who separately recognizes the CED and the Greenland Dog (Greenland listed as country of origin).

The policy of kennel clubs registering "Canadian Eskimo Dogs" and "Greenland Dogs" instead of identifying them as "Inuit Dogs" is an artificial contrivance, not based on the scientifically proven reality that the aboriginal Canadian Inuit Dog and the aboriginal Greenland Dog are indeed the same landrace. In his 1991 masters thesis, The Inuit Dog: Its Provenance, Environment and History, MacRury describes the Inuit Dog as one landrace that was found from Alaska to Greenland, based on the migration pattern of ancient Inuit ancestors and archaeological findings at early living sites. This was later confirmed for the first time ever by DNA analysis. In her Veterinary Masters Thesis, Dr. Hanne Friis Andersen states, "…there is no genetic evidence that states the presence of two different dog breeds in the native Arctic. From a geneticist’s point of view, based on this study the Canadian Inuit dog and Greenland dog is one breed divided into subpopulations."1

The name "Eskimo" is a corruption of a name assigned by non-Inuit more than a century ago. It has long since been considered pejorative, and the name was almost entirely abandoned at the time of the first Inuit Circumpolar Conference held in Barrow, Alaska in 1977 when "Inuit", meaning The People, was officially adopted. Honoring the desire to be identified as "Inuit" is not an issue of political correctness, but a matter of respecting the wishes of those who prefer to be called by a name of their own choosing, not one assigned to them by another culture. However, the term "Eskimo" is still used in an historic sense. And it is appropriate to identify Alaskan Yupik/Aleut as "Eskimo". The word is also used in the world of cultured all breed kennel club registered dogs, including the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC) who registers both the CED and the Greenland Dog (The CKC offers a massively confusing description of the Greenland Dog as follows: “Since the Inuit people of Canada’s Arctic were known to have emigrated from Greenland many centuries ago bringing their sled dogs with them, it’s possible this hardy polar Spitz breed is the forerunner of our native Canadian Eskimo Dog.”), The Kennel Club (Great Britain) who registers separately a CED and a Greenland Dog (calling it native to Greenland), and the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) who separately recognizes the CED and the Greenland Dog (Greenland listed as country of origin).

The policy of kennel clubs registering "Canadian Eskimo Dogs" and "Greenland Dogs" instead of identifying them as "Inuit Dogs" is an artificial contrivance, not based on the scientifically proven reality that the aboriginal Canadian Inuit Dog and the aboriginal Greenland Dog are indeed the same landrace. In his 1991 masters thesis, The Inuit Dog: Its Provenance, Environment and History, MacRury describes the Inuit Dog as one landrace that was found from Alaska to Greenland, based on the migration pattern of ancient Inuit ancestors and archaeological findings at early living sites. This was later confirmed for the first time ever by DNA analysis. In her Veterinary Masters Thesis, Dr. Hanne Friis Andersen states, "…there is no genetic evidence that states the presence of two different dog breeds in the native Arctic. From a geneticist’s point of view, based on this study the Canadian Inuit dog and Greenland dog is one breed divided into subpopulations."1

|

Inuit Dogs

in the Baffin Region |

Inuit Dogs

in Sermiligaaq, East

|

In 1990s era issues of the Canadian Eskimo Dog Gazette mention was made of Canadian Eskimo Dog Association (CEDA) members discussing voting to change the name to Canadian Inuit Dog and then petitioning the CKC to make the change official. That proposal seemed to have died away. Recently however, here and there on websites fanciers of dogs for show and pet now identify their animals as "Canadian Eskimo/Inuit Dogs" or "CED/CID". And there has once again appeared a movement to petition kennel club registries to change the official name. Trying to understand why this is happening would be merely speculative. Changing the name, officially or otherwise, of the kennel club registered (or hope to be registered) dog from "Canadian Eskimo Dog" to "Canadian Inuit Dog" or whatever would be like a sleight-of-hand deception. Owner/breeders could hide their "cultured" dogs bred to show and pet standards behind the true aboriginal dog that can actually perform as their ancestors have done. The distinctions between what the aboriginal Canadian Inuit Dog represents and can do and what the kennel club registered Canadian Eskimo Dog represents but cannot do should be defined at least in part by their different labels.

B. Defining 'purity'

The question has also been

asked, "Is an Inuit Dog a pure breed?" To those wedded to

the world of all-breed kennel club registered dogs, purity

is defined as a multi-generational pedigree consecrated by

an official club registration number. Others who

understand and respect the nature of aboriginal landrace

dogs know that:

Having traveled extensively throughout the Canadian Arctic, Bill Carpenter and John McGrath were alarmed by the dwindling numbers of traditional dogs seen. In the early 1970s they established the Eskimo Dog Recovery Project. The two men collected examples of dogs from working teams across the Arctic and bred them at Carpenter's kennel in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada. The endeavor was a success in that it resulted in a revitalized number of these aboriginal dogs. In order to "validate" their work, those animals were registered with the Canadian Kennel Club.3 Some of the Recovery Project dogs were placed with breeders who lived in the Arctic and elsewhere below the tree line who reproduced and used them strictly as working dogs. And it is from those sources that represent some but not all of the today's authentic traditional stock remaining in the Arctic, now identified as Inuit Dogs or Inuit Sled Dogs. Other dogs from the Recovery Project were taken up by the Canadian Kennel Club dog show and pet fancy. This was an unintended consequence, at least according to Carpenter and McGrath. Eschewing the world of show dogs and pets, Carpenter said in a January 31, 2001 New York Times interview:

"The word "purebred" is an invention of the modern dog world. Due to environmental isolation and survival of the fittest, landraces are pure."2This concept may be incomprehensible or at best poorly digested by average "cultured dog breed" pet owners and it is often vigorously rejected by breeders of show and pet dogs who insist that only dogs whose parentage can be listed on a validated pedigree form are "purebred." Yet at the same time these very people cling tightly to and advertise with great enthusiasm their romantic representation of an ancestral/authentic history (one lacking kennel club registries), despite their own dogs being diluted by time and change in habitat and the loss of traditional working skills during their conversion to show/pet lifestyles.

Having traveled extensively throughout the Canadian Arctic, Bill Carpenter and John McGrath were alarmed by the dwindling numbers of traditional dogs seen. In the early 1970s they established the Eskimo Dog Recovery Project. The two men collected examples of dogs from working teams across the Arctic and bred them at Carpenter's kennel in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada. The endeavor was a success in that it resulted in a revitalized number of these aboriginal dogs. In order to "validate" their work, those animals were registered with the Canadian Kennel Club.3 Some of the Recovery Project dogs were placed with breeders who lived in the Arctic and elsewhere below the tree line who reproduced and used them strictly as working dogs. And it is from those sources that represent some but not all of the today's authentic traditional stock remaining in the Arctic, now identified as Inuit Dogs or Inuit Sled Dogs. Other dogs from the Recovery Project were taken up by the Canadian Kennel Club dog show and pet fancy. This was an unintended consequence, at least according to Carpenter and McGrath. Eschewing the world of show dogs and pets, Carpenter said in a January 31, 2001 New York Times interview:

"The future of this dog is not with southern dog shows, not with pet owners on leashes. The future of this dog lies in its cultural setting. The future of the dog is in the hands of the northerners."Because some of these CKC registered dogs can be traced back to the Recovery Project does not mean that these are the only "pure" dogs remaining as has been claimed.4 It simply indicates that this is a population of dogs whose lineage is known back to the Recovery Project.

C.

Mistaken Identity: Promoting a breed vs. avoiding

extinction

Back in late 19th

century Victorian England the keeping, breeding and

creating of new breeds of dogs strictly as pets and

for competition at shows became hugely popular and

is acknowledged as the beginning of the end for the

functional skills of many working breeds.5 Yet

today naïve enthusiasts believe they can "save the

rare Eskimo Dog" by "promoting the breed" through

making and selling puppies, exhibiting at dog shows,

displaying cute photographs of their dogs and

children and racing their dogs for a few kilometers

in front of a wheeled cart or occasionally a sled.

As long as they are referring only to the registered

show/pet dog, they may (or may not) be correct.

However, as promoting in this manner is not

synonymous with avoiding extinction, they are wrong

in believing their dogs are the same as authentic

aboriginal dogs of Canada and Greenland.

|

These are the prizes for winning a beauty contest. |

The prize

for good working dogs in an Antarctic ground

blizzard is you get to live. Photo: Drummond Small |

Enthusiasts of kennel club

registered dogs have also conducted a media campaign to

try to convince (and therefore have misled) the public

that their breed is endangered and in need of government

involvement in a rescue effort.6

Publically pleading their case, they cited a high point

population of some 20,000 dogs, which represents a figure

used by Inuit organizations as the population of

aboriginal dogs prior to 1950, down to a low point of 200

or so which represents the number of CKC registered dogs,

the real object of their lament – a comparison of apples

to oranges. While traceable back to the Eskimo Dog

Recovery Project, these dogs have been bred to a show

standard and as pets, not strict adherence to traditional

performance and challenged by the severe polar conditions

which selects for the most capable and heartiest stock.

This has impacted on the dogs' original identity.

Some mushers keeping other than these aboriginal dogs have sought to whittle away at the Inuit Dog's persona. It is their illogical belief that since the dog no longer needs to hunt polar bear, it no longer needs to retain its legendary Inuit Dog temperament (mistakenly assuming that the dog's temperament is solely a consequence of its hunting skills). This aspect of the Inuit Dog presents a management challenge for many sled dog keepers who either cannot or do not want to cope with this landrace.

Members of the non-mushing community also seek to chip away at the authentic Inuit Dog:

Some mushers keeping other than these aboriginal dogs have sought to whittle away at the Inuit Dog's persona. It is their illogical belief that since the dog no longer needs to hunt polar bear, it no longer needs to retain its legendary Inuit Dog temperament (mistakenly assuming that the dog's temperament is solely a consequence of its hunting skills). This aspect of the Inuit Dog presents a management challenge for many sled dog keepers who either cannot or do not want to cope with this landrace.

Members of the non-mushing community also seek to chip away at the authentic Inuit Dog:

"Nowadays not so much people need a [Canadian

Eskimo/Inuit] dog to pull a sled, so probably taking

them to shows or exhibitions, or, in general, spread the

word about them, might save them in the future…"7

This equally illogical

concept of "saving" a breed is actually what destroys it!

Champagne would not be champagne without the bubbles.

Lacking the effort to re-cork the bottle, the contents go

flat. Breeders cannot pick and choose characteristics that

fit in with their limited dog handling skills, their

lifestyles and of those to whom they hope to peddle their

puppies. Ignoring the characteristics that are hallmarks

of the Inuit Dog, will result in changes so profound that

the outcome is the creation of a different breed

altogether.

D. The Belyaev ExperimentBack in the mid-20th

century, Russian geneticist Dr. Dmitry Belyaev began a

groundbreaking experiment in an effort to study the

evolution of dog domestication. On a Siberian fur fox

farm, he bred only those animals with the least flight

distance from humans to see if they could be

tamed/domesticated. The results were startling. Aside from

an increasingly biddable dog-like behavior, the appearance

of a typical wild silver fox morphed to display features

found in domestic dogs: piebald coats, floppy ears, blue

eyes, curled tails. .8

|

|

| Selection

based on behavior alone has resulted in the

dramatic change from terrified of human approach

and wild type coat color (left) to social

attraction and a piebald coat color pattern

right). |

These photos were taken in

Novosibirsk on the experimental farm of the

Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the

Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy

of Science. |

The lesson of what happens when selection is made on the basis of a behavior not native to the original animal is one that resonates with aboriginal dog enthusiasts, in this case Inuit Dogs. Misguided owner-breeders of kennel club registered Eskimo Dogs and Greenland Dogs are too intent on their mission to "save the breed" even if they cannot possibly (nor do they want to) duplicate the same environment and working conditions to honestly keep it from going extinct. What they refuse to accept, for any number of reasons, is that what they have in their back yards can be described as the equivalent of Belyaev's genetically (behaviorally) modified fur foxes. If someone wanted to wear a silver fox coat, it is not likely that they would think one that had blotches of color like a pinto horse could be considered authentic. Although not referring to a change in phenotype as seen in the side-by-side fox images above, reproduction of dogs not consistent with their traditional characteristics will mean a loss of the essential survival and working abilities, alterations not necessarily visible to the naked eye, but gone nonetheless.

Belyaev's work is a critical contribution to the argument that aboriginal dogs can only remain so by being challenged by climate and work as performed in their native habitats to remain as they have been for centuries, or even millennia..

E.

Summary

This paper presumably proves "purity." Purity proving itself in the work environment.

Photo: K. Suboch

The official CKC breed

standard makes no meaningful/useful mention of working

ability. While it lists faults and disqualifications, some

of which relate to what an authentic dog ought not look

like (albeit ignoring the natural range that one would

expect in an aboriginal landrace), there are no faults or

disqualifications relating to its actual capabilities.

| Pedigree (purity) alone without validation of performance does not confer breeding worthiness. The dogs must do more than "talk the talk" to truly be considered authentic. The dogs must prove they can "walk the walk". |

"It looks good on paper, Leonardo,

but will it

fly?"

Leonardo DaVinci's vision of a helicopter,

also called the "ariel-screw"

In his thesis, MacRury

emphasizes the absolute need for performance based

breeding.9

He recounted the story of a Baffin Island community that

at one point had no working teams, then obtained from all

over the region a variety of dogs that neither performed

well nor "looked the part". But after four or five years

of intense selection and culling, the resulting dogs

exemplified the most authentic type in appearance,

behavior and capabilities10.

In a June 21, 1988 New

York Times interview eminent behavioral

geneticist, Dr. Benson E. Ginsburg, Professor Emeritus at

the University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, said,

"Genetic variability is

built into a species so it can adapt if conditions

change. In wild forms, the coyote and wolf, there are

what we call buffering systems so that genes they have

are not necessarily expressed. In domestication [here

referring to cultured breeds], the system of genes that

buffer differences from the norm are bred out.''

Dr. Ginsburg concluded, ''We

have selected away from the buffering system, so all

possibilities can appear, and dogs can freely show all

their genetic variability." It may have taken

four or five years for that Baffin Island community to

restore the Inuit Dog, but it is certain that it takes a

lot less time, perhaps a carelessly bred generation or

two, to destroy a landrace!

So the answer to the question, "Is the Canadian Inuit Dog/Greenland Dog/Inuit Sled Dog the same as the Canadian Eskimo Dog?" is both "yes" and "no". The two names are not interchangeable when one is comparing dogs bred based on their ability to thrive and work in their native habitat (Canadian Inuit Dog) and the other is being promoted, owned, kept and bred essentially as a cultured pet/show dog (Canadian Eskimo Dog)! The genetic origins may be the same but only through culling and selection based on arctic conditions and successful work may return the CED to being the dog of its predecessors. One thing is certain. The real endangered species is not the registered show dog, but the aboriginal landrace of the North.

1 Population Genetic Analyses of

the Greenland dog and Canadian Inuit dog, May 2005 by Dr.

Hanne Friis Andersen, Royal Veterinary and Agricultural

University, Frederiksberg, Denmark.So the answer to the question, "Is the Canadian Inuit Dog/Greenland Dog/Inuit Sled Dog the same as the Canadian Eskimo Dog?" is both "yes" and "no". The two names are not interchangeable when one is comparing dogs bred based on their ability to thrive and work in their native habitat (Canadian Inuit Dog) and the other is being promoted, owned, kept and bred essentially as a cultured pet/show dog (Canadian Eskimo Dog)! The genetic origins may be the same but only through culling and selection based on arctic conditions and successful work may return the CED to being the dog of its predecessors. One thing is certain. The real endangered species is not the registered show dog, but the aboriginal landrace of the North.

2 ”Breed, Landrace and Purity: What do they mean?” by Edith and Johan Gallant, The Fan Hitch Journal, V13, N1; December 2010

3 The Canadian Eskimo Dog had already been registered by both the Canadian and American Kennel Clubs, the latter decertifying the breed sometime in the 1950s due to lack of sufficient numbers.

4 From a July 2002 sled dog email discussion list, “…the Canadian Eskimo Dog Association of Canada which is an international group. Please do not feel it necessary to be "P.C" [politically correct] and change the name as the dogs are officially recognized by the CKC as well as the Ministry of Agriculture as the above name. As an aside - "inuit dogs" refer to a crossbred version of our dogs, as well as one Canadian version of the alaskan version - gets very confusing. Thanks.” N.D. Nicole Doyon, Secretary/Photographer - Canadian Eskimo Dog Association of Canada.”

5 Dogs That Changed the World;

Evolutionary Changes In Domesticated Dogs: The Broken Covenant Of The Wild, Part 1 and Part 3 - Cultured Breeds and Show-Pet Dogs.

6 See: The Games People Play: Save the Sled Dog or Save the Show Dog, The Fan Hitch, V6N2, March 2004

7 Debora Segna, personal communication, April 2012.

8 How to Tame a Fox: (and Build a Dog) Visionary Scientists and a Siberian Tale of Jump-Started Evolution by Lee Alan Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut

9 The Inuit Dog: Its Provenance, Environment and History; Ian Kenneth MacRury. Chapter 1, pg 5, pp 3.

10 Personal communication.