From the Editor: Taxonomy

Taxonomy in Relation to the Inuit Dog

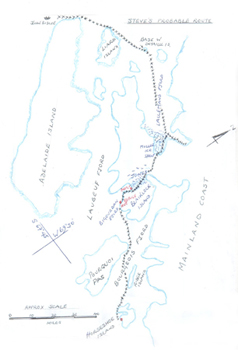

Steve’s Solo Journey

In the News

Far Fur Country Progress Report

Digital Indigenous Democracy Comes to the Canadian North

Media Review: Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts

New Printing of Inuit Dog Thesis

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

Steve (l) and Porgy at Base W Photo: Robin Perry

Steve’s Solo Journey

Peter Gibbs

February 2014

It was early March 1959. The John Biscoe under Skipper Johnston was due to relieve the four of us from the southern most Stonington Island Base. But the ice in Marguerite Bay on the west-central side of the Antarctic Peninsula was shore-fast to the horizon. Doc Henry Wyatt, Pete Forster, Keith Hoskins and I battened down the old hut windows and door and loaded up five sledges to the four teams of dogs. With my team, the Admirals, hauling two of the sledges, we quickly sledged some thirty miles up to Horseshoe Island’s Base Y on weathered but wind-blasted ice. The Admirals showed off their amazing capabilities as if knowing it was my last journey.

Satellite image of Antarctica with the peninsula circled in red.

Orthographic projection of NASA's Blue Marble data set,

Dave Pape/Anna Frodesiak. Modified by Agis Fasseas.

The Americans heard of the Biscoe’s fast ice difficulties and sent the icebreaker Northwind and two helicopters to assist. In spite of her power Northwind could not smash a passage through four-foot ice into Horseshoe Base without difficulty and delay and the four of us were flown forty miles out to the ships, leaving the four dog teams at Base Y. Over the next two weeks Northwind very slowly broke a passage from the edge of bay ice at the southern end of Adelaide Island up its west coast with the Biscoe having to be towed by steel cable at times in the icebreaker’s wake. By the 31st of March the two ships reached the Matha Strait to pick up all the men and the six dog teams of Base W Detaille Island (under Brian Foote) that had been closed by policy. They sledged to the ships some forty miles away, the last three teams arriving at the ships just north of Adelaide Island ice piedmont at 0230 hours on the first of April. I was asleep but with some others was awoken to help tether the teams and get them and the kit aboard...quite simple with obedient husky co-operation. However, one of them, Steve, did not trust these strange guys with their entreaties and slipping his harness he scampered free. With temperatures dropping to +10F (-12C) and new ice forming Skipper Johnston could not risk being beset so he ordered passage northwards while those of us at the rail watched Steve’s wolf-like forlorn figure getting smaller until out of sight but not out of mind. None of us thought he stood a chance, although we had worked with these dogs for two years and witnessed ten of the fourteen dogs survive a fatal break up of winter ice that killed three men from Horseshoe on their way to the Dion Islands. Yet with Base W closed we assumed Steve had sealed his own fate.

We underestimated the incredible resourcefulness and staying power of the husky. Steve turned up about three months later at Horseshoe Island, paws bleeding and sore but tail wagging and tongue lolling as the new base personnel had to believe their eyes. Robin Perry was the new leader at Horseshoe Base. This is his account:

“A few days before the feast of midwinter (1959) a strange dog was noticed creating a hullabaloo among the teams out on the spans. I had no difficulty in recognizing Steve. He had been on the loose for nearly three months and seemed pleased to find people again. I attached him among the Spartans where he was not exactly well received at first! We found he was a good 20lbs above his normal weight, but in excellent form. I speculated that he had gorged himself on the seal pile left at Base W then felt the need for the company of the pack. He had done the journey from Base Y (Horseshoe) to W the previous year so that may have helped him find his way over the glaciers and sea ice.”

This is the story of Steve’s journey, surmised from the midwinter round trip travels Doc Sandy Imray and I did from Horseshoe Island to Detaille Island via the Blaiklock Island Refuge, the sea ice having now set to enable this. Having celebrated one mid-winter party at Horseshoe, we accompanied Angus Erskine and Jim Madell who had completed an autumn journey on the plateau and were returning to their Base W. Steve was not a lead dog but a recollection of this more southerly base and the route that was taken must have stayed in his mind.

The first forty miles from the ships across good ice with fresh tracks to Detaille Island was swift and Steve could follow the scent of pee marks on many bergy bits. Not having worked out that the base was closed with no men or dogs there to welcome him back to his home, he was indeed bemused to find nothing but a boarded up hut and silent spans and chains. He sat on his haunches and let out a prolonged wolfy howl.

Evensong at Adelaide, an un-named husky giving vent to emotion.

Photo: Geoff Renner

from Of Dogs and Men by Kevin Walton and Rick Atkinson;

Published by Images of Malvern, 1996

A few seconds later the silence was broken by the echo of his own wail from Liard Island to the west and the buttresses of Murphy Glacier on the mainland to the east. He pricked up his ears looking one way then the other. It had never been so calm and quiet to notice before these echoes like ghost dogs. He could not settle and traversed the island sniffing the air and looking. Maybe one of the base party was still here or they would come with a team of his mates. One big consolation was the seal pile. The carcasses were not hard frozen and the night of his journey had given him an appetite. Skuas had opened up the hide of the topmost seal. Steve tore at the carcass, lunging at the skuas who glided noisily just out of reach. Satiated, he lay down by the steps to the hut where the drifted snow of winter had thawed and left a shelter partly under the hut.His journey was over. He deserved to feel proud but that is a human sentiment. He had covered at least 140 miles.

A full belly and confident reasoning that before long he would hear the “Huit huit” (go, go), “Irrre irrre!” (left, left) and “Auk, auk” (right, right) shouts of a dog driver and catch the team’s scent, lent comfort and hope to his lonely vigil. But day after day passed. The sun set behind Liard Island, the days grew shorter and the nights colder. No men and no dogs came. A blizzard blew down the Murphy Glacier picking up all the summer snow in a blind fury. Steve sheltered by the steps to the hut and became drifted over. Nose tucked into tail he curled up for days until he sensed it quiet above and breaking the crust shook himself free. He had experienced many lie-ups before on the trail, one lasting ten days when in the following calm the drivers would dig out the dogs and tent getting all onto the new surface now three feet or more higher. His stiff fellow dogs would stretch their legs whining and eager to get on the move while growling at sparring partners. The recollection triggered a yen to be back on the trail with fellow mates obedient to their human masters, hauling in harness every ounce of their own 115-pound weight. He had to leave the comfort of his seal pile and find company again somewhere south over frozen fjords and glaciers. With hindquarters to the sun he started south up Lallemand Fjord following his shadow and memory of a previous journey when Bodger was leading.

In southern Lallemand Fjord he got lost in a graveyard of grounded icebergs with high drifts between them. So he back-tracked climbing over high pressure ridges. Skirting the mountains to the west he rounded Hooke Point, now recognizing features from his previous journey between the bases. The ice was rapidly melting, ready for a late summer break out. Steve swam across melt pools. An incautious penguin that torpedoed onto a flow in his path provided a welcome meal. They, along with the skuas, petrels and terns were preparing to migrate northwards. The Muller Ice Shelf blocked his path but he found access onto it where it abutted a rocky slope. Here in an area of absolute calm the temperature fell and it snowed soft feathery flakes, blotting out visibility and sense of direction. The accumulating snow had no substance to it. Like a mole the husky tried to tunnel forwards but wisely he conserved energy and lay up, floundering to the surface as needed. After some days a katabatic wind raised clouds of drift and gave the surface enough firmness to allow him to continue his journey, and as he climbed to the top of the Heim Glacier he could trot and jump the sastrugi ridges. He sensed black holes where snow bridges had collapsed and cautiously pawing forward on his belly he crossed the sunken bridges. Had he plunged into a crevasse there would have been no story to relate. But providence and will come to the aid of the lone survivors the likes of Mawson and Osman, whether man or dog. Steve skirted the ice scoops on the Jones Shelf and made for the depot on the beach of Bigourdan Fjord. Tearing open a box of pemmican he restored his energy for the last eight miles on rotten ice to the Refuge hut on the west coast of Blaiklock Island. It was deserted but scents of men, dogs and especially some manky seals above the high water mark buoyed his spirits. Can huskies count days or appreciate awesome scenery? Mount Thor as we called the 7500 ft high massif sent down avalanches into the head of Bigourdan Fjord. The Reid Glacier shone rosy tints as the midday sun just skimmed its horizon. Fast ice covered the fjord and new ice was forming across the melt pools. Now sustained by his rest and seal feeds he loped and swam the last twenty-five miles through the Narrows and down to Ridge Island, galloping the last two miles as the scent of men and dogs grew stronger, finally greeting his fellow mates on the span.

I wish to thank Denis Goldring for details of the Base W exit and to Robin Perry for comments and the photo of Steve and look-alike twin Porgy.