From the Editor: Taxonomy

Taxonomy in Relation to the Inuit Dog

Steve’s Solo Journey

In the News

Far Fur Country Progress Report

Digital Indigenous Democracy Comes to the Canadian North

Media Review: Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts

New Printing of Inuit Dog Thesis

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

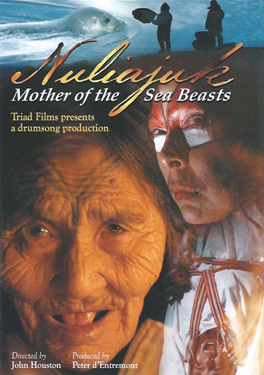

Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

The title of this intriguing film belies its complexity and depth. Only in part is it the history of the most powerful and feared Inuit deity who, as an independent-minded young woman, suffered trickery, adversity and brutality before becoming the Mother of the Sea Beasts as well as the mother of Native North Americans and white people.

Nuliajuk (pronounced noo-li-AH-yook), or Sedna as She is more commonly known, refused to marry the man her father chose for her. Angered by her obstinacy, he tricked her into marrying his lead dog who first appeared to her as a handsome man. Her pregnancy resulted half the young turning out more like their Inuk mother and they became the First Nations / Native Americans while the other half took after their dog father, becoming Qallunaat (white people). Her father eventually exiled his daughter and her young to an island and had her husband take food there. But Nuliajuk’s father deliberately drowned her dog-husband and thus became his daughter’s sole provider. On his arrival at the island with food, Nuliajuk instructed her children to tear him to pieces. Now, with no food source, Nuliajuk set her children out to sea. She instructed her dog-children to return when they learned to support themselves.

Alone on the island, she falls in love with a sea bird disguised as a human and they go out to sea in his kayak. While resting on an ice floe, she sees his short legs and realizes she has been tricked once again, this time into marrying a bird. She screams for help and her father comes back to life and to her rescue. They escape by boat but the sea bird goes after them. Fearing the angry bird, Nuliajuk’s father pushes her out of the boat. As she desperately tries to hang on her father chops off her fingers, knuckle by knuckle, and as the pieces fall into the sea they become all the different seals and whales. Nuliajuk descends to the bottom of the sea having become the Creator and Mother of the sea beasts.

According to the film’s director, John Houston (who is also the narrator) Inuit perception of Nuliajuk’s 10,000-year history as omnipotent giver and withholder of sustenance (in the form of successful or unsuccessful hunting) began to change about a century ago with the arrival of whalers and the unrelenting influence of the church. These men on ships had the ability to successfully harvest the largest beast of the sea, bowhead whales, seemingly without need of Nuliajuk’s benevolence. In converting the “godless pagans” to its own doctrines, the church subjugated Inuit and compelled them to turn their backs on their own supreme deity to instead worship a god foreign to them. So back in the 1800s these two groups represented “a force other than Nuliajuk dispensing new and exotic bounty” and ways of life, cutting the heart out of Inuit spirituality and the vital link to the natural world of which they were a part, diminishing the all-powerful Nuliajuk in different ways, ripping out the underpinnings of this aboriginal culture. Some Inuit who became staunch Christians went as far as to completely turn their back on Nuliajuk, refusing to speak of Her to their children.

John Houston during the directing of Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts

Photo: Chris Ball

For Houston, the making of Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts was a personal journey, having spent a happy childhood in the Canadian North with Inuit he came to feel were his extended family. He describes returning to the North as a dog-man to learn of his roots, as if he were struggling to find his own place somewhere between his childhood with Inuit friends and “family” and his modern adult world.

To learn and understand the history of Nuliajuk’s life, Houston brings a present day Danish ethnographer along on the journey, as well as examines the work of Knud Rasmussen (1922). Nearly eighty years later, John and the ethnologist are hearing stories about Her identical to those told to Rasmussen by Inuit. Viewers will also see Houston interview Inuit and white Anglican ministers, retired shamans and Elders to understand their relationship with Nuliajuk both before and after their religious redirection to the church. He learns that many sincerely regretted allowing their conversion to Christianity to steer them away from traditional spirituality. This dichotomy is seen as another example of Inuit struggles between their historical way of life and the intrusion of the modern world. And as Houston heard, “Some Inuit are [now] reaching back to go forward.”

Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts includes many scenes depicting Her life story in the form of an incredible performance by Greenland’s Tukak Theater troupe. Inuit transformation in attitude towards Nuliajuk under the influence of the outside world and Houston’s own search for self enlightenment are skillfully told using the rich imagery of Inuit prints and carvings, captivating photos and films of Inuit culture and traditions from very long ago (including Knud Rasmussen’s travels by dog team) and today and interviews with Elders (English subtitles). Everything about this film is riveting, but what I find especially appealing is the gorgeous photography of Inuit, many of them Elders, being interviewed. Watching their faces – sculpted by exposure to the elements, some by traditional tattoos and by age and life on the land – while narrating recollections of lives ruled by Nuliajuk’s impulses, gives me a sense of what treasures Elders are. Clearly Houston knew this as well and we should be grateful that he did. Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts would be a valued addition to your polar video library.

Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts has won many awards: 2002 Golden Sheaf Award, Best Multicultural/Race

Relations at the Yorkton Short Film and Video Festival; 2002 Award for Outstanding Achievement in a Documentary 1st Directors Guild of Canada Awards; 2002 Winner of a Bronze Plaque at the 50th Annual Columbus International Film & Video Festival; 2002 Winner of the Bee Cinematography Award/Documentary New York International Independent Film & Video Festival. It was made in 2001 by Triad Film Production and drumsong communications, inc. It is 50 minutes, 51 seconds long. Along with five other Houston films about the North, it is available from:

Northernspring Inc.

DVD Subdistributor: Ree Brennin Houston, President

5455 Inglis Street

Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3H 1J6

Tel: 902-422-7174

email: ree@redshift.com

Houston North Gallery

To see the complete list of available Houston films along with a fine gallery of available northern art created in various disciplines, please visit the online Houston North Gallery.