From the Editor: Taxonomy

Taxonomy in Relation to the Inuit Dog

Steve’s Solo Journey

In the News

Far Fur Country Progress Report

Digital Indigenous Democracy Comes to the Canadian North

Media Review: Nuliajuk: Mother of the Sea Beasts

New Printing of Inuit Dog Thesis

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of back issues by volume number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch, Journal

of the Inuit Sled Dog, is published four

times a year. It is available at no cost

online at: https://thefanhitch.org.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

The Fan Hitch welcomes your letters, stories, comments and suggestions. The editorial staff reserves the right to edit submissions used for publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org.

This site is dedicated to the Inuit Dog as well as related Inuit culture and traditions. It is also home to The Fan Hitch, Journal of the Inuit Sled Dog.

From: Turner J. Sidney, (undated) The Kennel Encyclopaedia Volume II,

The Kennel Ltd., Sir W.C. Leng & Co Ltd., Sheffield, England

Taxonomy in Relation to the Inuit Dog1

and Major Historical References to the Breed

by William J. Carpenter

In the Webster Dictionary (1982) taxonomy is defined in its simplest meaning as the “classification, especially of animals and plants.” As a noun Chambers Concise Dictionary (1991) defines it as “classifications or its principles; classification of plants and animals, including the study of the means by which the formation of species etc. takes place.” From the Encyclopædia Britannica online (undated), the free encyclopedia defines taxonomy (general) as “the practice and science (study) of classification of things or concepts, including the principles that underlie such classification”; and taxonomy (biology), “a field of science that encompasses the description, identification, nomenclature, and classification of organisms.”

Allen (1920) in his book Dogs of the American Aborigines (which many people consider to be the earliest definitive work on the topic) made reference to Walter Hund in 1817 as the earliest taxonomy of the Eskimo dog as Canis familiaris sibericus groenlandicus. Allen identified seventeen breeds or types indigenous to the western hemisphere at the time of European contact. These were placed into three groups (Allen, p. 503) based largely on travelers’ accounts and skeletal remains. Eleven fit into what he calls the larger Indian dog type, five into the smaller Indian Dog type while the “Eskimo Dog”, or as the Inuit called it, “qimmiq”, was the sole occupant of the third group. He also referenced Canis familiaris borealis (Desmarest, 1820) followed by Canis borealis (Smith, 1840).

Borealis or boreal in an online dictionary means pertaining to (or of) the north, which is certainly the case with this aboriginal breed of dog, the Inuit Dog. Therefore, from an initial perspective the inclusion of the word “borealis” either by Desmarest or Smith had a direct and clear reference to the north that was the historic and originating home of this breed of dog.

Now in 2014, I have been informed (Hamilton, per communication, 2014) that most if not all modern day taxonomists insist all domestic dogs are simply Canis familiaris. During the course of preparing this paper, in addition to the above references I reviewed an additional nineteen articles and papers from my files dating as far back as the 1800s. What I was looking for was any reference to any scientific names or some mention of taxonomy. As noted below, in spite of significant historic papers and information I found nothing at all in the way of any taxonomic reference.

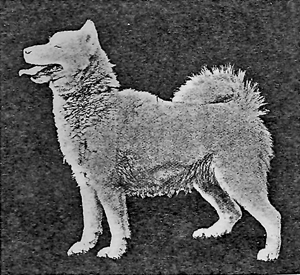

“Eskimo”

From Pure-Bred Dogs: The Breeds and Standards

as Recognized by the American Kennel Club, 1935

In Pure-Bred Dogs (1935, p. 275), the Eskimo Dog Club of America, stated: “The Eskimo dog, claimed by his admirers as the best-footed, toughest and strongest for his size of all breeds, is a native of the Arctic. Originating in all probability in Eastern Siberia he has since been taken by the Eskimo owners to Alaska, Northern Canada, Baffin Island, Labrador and Greenland...As a member of the so-called Spitz Group he is closely related to Alaskan Malamutes2, Siberian Huskies, Samoyeds and Chows3 and more distantly to others, including the Norwegian Elkhound, Finnish Spitz…” The article goes on to say: “As a work dog…he can pull heavier loads greater distances and on less food than almost any other living animal…” (p. 278).

In the Kennel Encyclopaedia Turner (undated, p. 594) writes: “…Being a native of Polar region…It will scarcely be questioned that this breed is the nearest approach to a wild animal of any of the canine tribe…” He goes on (p. 601) to say: “A peculiarity of the Eskimo (and one which indicates further the semi-wild nature of this dog) lies in the fact that he does not bark. The dog is quite incapable of doing so. Instead, he issues a spasmodic moan [howl in today’s terminology]…The Eskimo never becomes really domesticated in the sense that other dogs do…for he retains an apparently inborn tendency to attack other animals, however large, and will without hesitation, tackle and perhaps kill, a cow…” “In the feeding of these dogs…it is very essential that there should be an ample supply of meat and fish to keep them in anything like proper condition.” (p. 602).

From: Turner J. Sidney, (undated) The Kennel Encyclopaedia Volume II,

The Kennel Ltd., Sir W.C. Leng & Co Ltd., Sheffield, England

I recently read a Breeding-back Blog entry dated Wednesday, 19 February 2014, “Is the dog a domesticated wolf or something different?”. The blog had a very interesting text: “Dogs are adapted to a more starch-rich diet than wolves, this is either an adaptation to their domestic niche or a trait inherited from their wild ancestors. Generalist canids and feral dogs are opportunistic, voluntary human commensals that reproduce in human’s neighbourhood, while wolves never do so voluntarily. The former usually are meso- to hypo- carnivores, while wolves, being the largest extant canids, regularly take down big game.”

It is not just wolves that take down big game. I can personally attest to the ability of Eskimo Dogs to instinctively hunt and kill prey. During the construction period of the Polaris Mine on Little Cornwallis Island in the Canadian High Arctic during 1979 and 1980 I had a contract with Bechtel Engineering who was building the mine facilities. I was running a polar bear deterrent program to keep man and bear apart as Little Cornwallis Island had one of the highest polar bear densities in the area and during peak construction there were several hundred construction workers rotating in and out of the site. As well as delivering an education program, I had two packs of Inuit Dogs at the site each with a pack leader or boss dog and each pack having its own territory, as set out by feeding areas and having walked the boss dogs on lines to let them mark their own territory with frequent urination spots. The process of establishing separate zones or territories worked extremely well so as to provide dogs in the two areas to keep bears away. They were under the care of an Inuit Elder who had dogs most of his life. I won’t go into detail as to how well the polar bear deterrent program worked but suffice it to say it worked very well and numerous cases were documented of the dogs chasing bears away from the site. However near the end of the program the dogs from the north pack decided to wander off to the west and explore. They ended up on Bathurst Island having travelled over the sea ice, and for a three-week period until we got them back they hunted, killed and ate several caribou that were on the island. On one occasion in Yellowknife I looked out my window only to see several three-month-old Inuit Dog puppies that had escaped from their pen chasing our pet goat and nipping at her legs trying to bring her down. They failed only because I intervened.

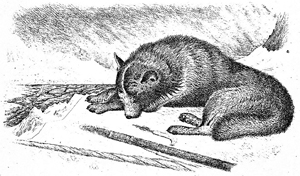

The Greenland Dog

By Reinagle; from Taplin’s Sportsman’s Cabinet; 1803

As to being meat eaters, from my own personal experience in the 1970s when first raising Inuit Dogs in Yellowknife, NWT using donated commercial dog food high in starch and with grain based protein, my dogs and puppies were plagued with constant diarrhoea and weight loss. It was only when I switched to raw meat/fish and fat that they fully recovered. Raw meat and/or fish plus at least 35 to 50% fat remained the sole diet for all Inuit Dogs I raised or took on long distance trips. Under cold working conditions they received as high as 7,000 kcal per day. MacRury (1991, p. 30) first quotes Perry in The North Pole (1910, p. 74) “…Their food is meat and meat only.” MacRury goes on to write “The Inuit Dog is naturally carnivorous…Its preferred food…is from marine mammals: seals, walrus, and…small whales…”

A great deal of research has gone into the feeding of sledge dogs primarily in relation to their use in the Arctic and Antarctic, including the British Antarctic Survey and the earlier Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey with dogs originating from Canada and Greenland. The research papers reviewed include those of Taylor (1957), Orr (1965), Wyatt (1963) and Adie (1953). The common theme in all the papers is the benefits of raw seal meat and blubber (or in the Arctic the meat would have included whale, walrus or bear as well as seal). Commercial pemmican (66% protein and 33% fat) and Nutrican (25% protein, 45% fat and 21% carbohydrates) were referenced by Orr (1965) but he illustrates the dogs always benefited more from raw red meat and blubber.

The Esquimaux Dog has also been referenced by Berjeau (1863) and others:

Jessie in 1866 said: “The dog [Esquimaux Dog] is the only domestic animal of these people [Esquimaux], whom he aids in draught and in chase …” (page 211); and again on page 245: “Of all the animals that live in these high latitudes, none are so deserving of being noticed as the dog.”

From Researches into the History of the British Dog

by George R. Jessie; 1866

“The Eskimo dog, sure footed, tough, and strong for his size, is a native of the Arctic...A product of the “survival of the fittest” over a period of at least two thousand years in rigorous localities, he is unsurpassed in his field. Not only does he provide a feasible means of transportation in winter, but he is an excellent pack animal in the summer…Since his employment by explorers...more rapid strides have been made in the Arctic and Antarctic than in the two preceding centuries.” (American Kennel Club, 1935, p. 147).

“Characteristics, measurements, size, weights and use, of in drawing sleighs...” (Dalziel et. al., 1897).

“The Esquima Dog – a moderately large dog of twenty-two to twenty-three inches in height, of wolf-like appearance…They are only half domesticated, though employed in large teams to draw sledges over the ice and snow of northern America…” (Mills, 1898).

“No doubt the number of expeditions to the Arctic regions of late years, and the keen public interest in all their details, has had the effect of bringing these dogs [Esquimaux], so important to all Arctic explorers, more to the front. There is a quaint, independent air about them…” (Moore, 1900).

Esquimaux Ch. Arctic King; Mrs. H.G. Brooke, owner

From All About Dogs; 1900; R. H. Moore

“The Labrador ‘husky’ dog is not different in appearance from the Alaskan Malamute…The pure white strain seen in Labrador and Ungava, on the other hand, is rare in Alaska.” (Hawkins, 1916).

“The Esquimaux Dogs; these dogs are the only beast of burden in the northern part of America and the adjacent islands, being sometimes employed to carry materials for hunting or the products of their chase on their backs…” (Walsh, 1919).

“The Eskimo is classified by the Kennel Club [Great Britain] as a distinct and respectable breed…” (Leighton, 1922).

“The early history of the Esquimaux …is of interest,” according to MacRury 1991, p. 10 quoting Kenyon (1975).

Frobisher (1577) mentions the use of sledge-dog.

Theodate (1636) writes, “They howl rather than bark …”

Ash (1927, p. 143), “In the history of the breed in England the Esquimaux dog was first allotted a class at the Kennel Club Show at the Agricultural Hall in 1888.”

Lawson (1932, p. 18) states, “The real Eskimo dogs are natives of Greenland, Labrador, and the northeastern part of North America…” and “This dog is classified by the Kennel Club as a distinct and respectable breed.”

Mills (1898, p. 80) also references and describes the Esquimaux Dog and adds: “They are only half domesticated …”

In some of my earlier writings, notes and presentations and as it has been used in the past, I used the scientific name of Canis familiaris borealis. MacRury (1991, p. 10) also used this name when he stated, “Since the identification of the Inuit Dog (Canis familiaris borealis) in the sixteenth century …” In providing me for review of the section he wrote on the Canadian Eskimo Dog, Dr. Bryan Cummins used Canis familiaris borealis. Then on May 1, 2000 the Legislative Assembly designated symbols of the newly formed Nunavut Territory to accompany Nunavut’s flag, coat of Arms and Mace, using the name Canis familiaris borealis to identify the territory’s chosen Official Animal, the Canadian Inuit Dog.

In recent years a great deal of work has gone into DNA studies on dogs of the Arctic. In 1999 I was first contacted by Janice Koler, founder of the Primitive and Aboriginal Dog Society. She had asked me to provide some hair samples from Canadian Inuit/Eskimo Dogs for an mtDNA study by Dr. Peter Savolainen, Institute of Biotechnology, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. Now we see more published studies on DNA including Brown’s work published in The Fan Hitch Volume 15, Number 2 March 2013 “ Antiquity Of the Inuit Sled Dog, Supported by Recent Ancient DNA Studies”. We also have the 2013 paper by van Asch et. al., “Pre-Columbian origins of Native American dog breeds, with only limited replacement by European dogs confirming mtDNA analysis”. Both papers reference the Arctic breeds of Inuit, Eskimo and Greenland dogs as seeming to constitute a separate genetic group who share a common gene pool including haplotype or sequence A31.

The question I raise is “Should the modern day taxonomists look at the unique and primitive features of the Inuit Dog in light of recent and ongoing mtDNA studies and other references to the Inuit Dog?” I believe the answer is certainly yes.

About the author:

William (Bill) Carpenter moved to the Northwest Territories (NWT) from Alberta in 1971, first working as a biologist with the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) and then later as a Senior Environmental Policy Advisor for the Executive Secretariat of the GNWT.

In 1974 he brought full time veterinary service to the NWT by building a clinic and hiring the first resident veterinarians for the North. On occasion Bill was himself a so-called para-vet as he often had to attend to the emergency needs of animal owners when his resident veterinarian was out of Yellowknife. For 21 years Bill provided this veterinary service to not only Yellowknife but all of the NWT.

In 1975 he left his government position and began his well-known work of preserving part of northern Canada's culture and history. This involved raising and breeding the indigenous Canadian Eskimo Dog (Qimmiq - the only domestic indigenous animal kept by the Inuit of Arctic Canada) which was then on the brink of extinction. The National Film Board of Canada produced a documentary film on Bill’s work called “Qimmiq – Canada’s Arctic Dog”. A second documentary called “Dogs of the Midnight Sun” by Summerhill Production shown on the Discovery Channel again covered the Canadian Eskimo Dog work undertaken by Bill Carpenter as well as others who used this indigenous breed of dog.

In 1979, to celebrate the opening of the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre and the retirement of then Commissioner S.M Hodgson, Bill and a companion undertook a 29 day dog sledging expedition from Resolute Bay to the southern tip of the Prince of Wales Island. In 1981, Bill also led a return expedition from Yellowknife to Hay River, circumnavigating the main body of Great Slave Lake with 4 teams of dogs to carry the mail to Hay River as a fund raising project of Rotary International.

In 1986 the first dogs from the “William J Carpenter Canadian Eskimo Dog Research Foundation” were registered with the Canadian Kennel Club. These dogs, many of which were given to other Canadian breeders, formed the basic stock for reviving the breed. Bill has written or co-authored several papers on the Canadian Eskimo Dog for presentation at universities, archaeological conferences and international symposiums. He also was involved in a Swedish based DNA research project on aboriginal dogs. The Canadian Inuit Dog as it is now called is one of the official symbols of the Government of Nunavut.

Bill has won conservation awards for his stewardship of the environment and in 2002 was a recipient of the Queen’s Jubilee Medal. He now lives in Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada where in “retirement” he continues to work on conservation projects.

ENDNOTES

1 It is worth noting that in the older literature this breed of dog was also called Esquimaux; Esquima, Esquimau Dog, Eskimo dog, Esquimaux, Esquimaux Huskie, Eskimo Huskie, Huskie & Husky. This was also often the case with the American Kennel Club (AKC), the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC) and the Kennel Club of England. CKC now calls the breed Canadian Eskimo Dog.

2 This certainly would have been the case in 1935. I previously read an article by Macbeth written for the AKC in the 1950s. Her references on the Malamute only go back to the late 1920s, then the only references are that of the Eskimo dog, the dog that the Thule people had across the entire Arctic.

3 The Chow is thought to be one of the oldest breeds of dogs (with recent DNA analysis confirming this) that probably originated on the high steppe regions of Siberia or Mongolia. Wikipedia

REFERENCES

Adie, Raymond J, 1953, Sledge Dogs of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey; reprinted from the Polar Record, Volume 6, Number 45, January 1958.

Allen, Glover, 1920; Dogs of the American Aborigines, Bulletin: Museum of Comparative Zoology.

American Kennel Club (undated) The Feeding, Care, and Handling of Pure-Bred Dogs, and the History and Standard of Every Breed Admitted to AKC Registration, Garden City Books, Garden City, New York.

Ash, Edward C., 1927; Dogs: Their History and Development Volume 1 p. 133-144; Ernest Benn Limited, London.

Berjeau, Charles, 1863; The Varieties of Dogs, Dulau & Co. 37 Soho Square, London, England.

Brown, Sarah K, 2013; Antiquity of the Inuit Sled Dog, Supported by Recent Ancient DNA Studies, The Fan Hitch Volume 15, Number 2 March 2013.

Chambers Concise Dictionary, New Edition; 1991, W R Chambers Ltd. P. 1097.

Dalziel Hugh, Gray D.J., Jagger Mrs., Piesse Alexander C., edited by Drury, W.D.; British Dogs, The History, Characteristics, Points, Club Standards and General Management, Vol. III, 1897; L. Upcott Gill, 170, Strand, WC London.

Desmarest, Mammology 1, 1820; p. 194.

En.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Encyclopædia_Britannica.

Hamilton, Sue, February 24, 2014; personal communication.

Hawkins, E.W., 1916; The Labrador Eskimo, No. 14 Anthropological Series, Geological Survey, Department of Mines, Government Printing Bureau, Ottawa.istory, V

Hund, Walter, 1817; p. 27.

http://dictionary.reference.com/

The Breeding-back Blog; Wednesday, 19 February 2014.

Jessie, George R., Researches into the History of the British Dog; 1866, Robert Hardwicke, 192, Piccadilly, London, p. 211, p. 245.

Lawson, James Gilchrist, The Book of Dogs, Photographs and Descriptions of the 103 Leading Breeds; 1932, Rand McNally & Company, Chicago.

Leighton, Robert, The Complete Book of the Dog; 1922, Cassell and Company, Ltd, London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne.

MacRury, Ian Kenneth, The Inuit Dog: Its Provenance, Environment and History; 1991; submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Polar Studies, Darwin College, Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Mills, Wesley, M.A., M.D., D.V.S. The Dog Book, A Manual on the Dog: His Origin, Varieties, Breeding, Education, and General Management in Health and Disease; 1898, T. Fisher Unwin, Paternoster Square, London.

Moore, R. H., All About Dogs, 1900; John Lane, London and New York.

Orr, N.W.M. 1965; The Food Requirements of Antarctic Sledge Dogs; Canine and Feline Nutritional Requirements, Proceedings of a Symposium organized by the British Small Animal Veterinary Association; London 1964.

Webster’s New World Dictionary, 1982; Warner Books, page 613.

Pure-Bred Dogs, The Breeds and Standards as Recognized by the American Kennel Club, 1935; Introduction by Charles T. Inglee, G. Howard Watt Inc. New York.

Smith, Hamilton, 1840 Jardine’s Nat. Library Mammalia 10, p. 127, plate 2.

Taylor R.J.F, 1957; The Breeding and Maintenance of Sledge Dogs, Polar Record 8, p 429. (published in two parts in The Fan Hitch. Part 1 here. Part 2 here.)

Turner J. Sidney, (undated); The Kennel Encyclopaedia Volume II, The Kennel Ltd., Sir W.C Leng & Co Ltd., Sheffield, England.

van Asch, Zhang, Oskarsson, Klutsch, Amorin and Savolainen, 2013; Pre-Columbian origins of Native American dog breeds, with only limited replacement by European dogs confirming mtDNA analysis; Published by the Royal Society B.

Walsh, J.H., The Dogs of Great Britain, America and Other Countries; 1919, Orange Judd Company, New York.

Wyatt, H.T., 1963; Further Experiments on the Nutrition of Sledge Dogs, British Journal of Nutrition Volume 17, p 273 – 279.