In this Post

From the

Editor: PostScript – From Famine to Feast

F.I.D.O.: From the Other Side of the World to Qimmiq Territory

Oh, those dog commands!

Dogs – One of the many reasons I loved them

Wally Herbert’s dogs – the Norwegian connection

Nansen Sledge Production

Langsomt på Svalbard (Slowly on Svalbard) Deferred for One Year

Book Review: QIMMEQ – The Greenland Sled Dog

Siu-Ling Han Memorial Scholarship

The Trip of a Lifetime

F.I.D.O.: From the Other Side of the World to Qimmiq Territory

Oh, those dog commands!

Dogs – One of the many reasons I loved them

Wally Herbert’s dogs – the Norwegian connection

Nansen Sledge Production

Langsomt på Svalbard (Slowly on Svalbard) Deferred for One Year

Book Review: QIMMEQ – The Greenland Sled Dog

Siu-Ling Han Memorial Scholarship

The Trip of a Lifetime

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor's/Publisher's

Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch Website and

Publications of the Inuit Sled Dog– the

quarterly Journal (retired

in 2018) and PostScript – are dedicated to the

aboriginal landrace traditional Inuit Sled

Dog as well as related Inuit culture and

traditions.

PostScript is

published intermittently as

material becomes available. Online access

is free at: https://thefanhitch.org.

PostScript welcomes your

letters, stories, comments and

suggestions. The editorial staff reserves

the right to edit submissions used for

publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

QIMMEQ

– The Greenland Sled Dog

Carsten Egevang, Editor

Members of the QIMMEQ Project, contributing authors

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

Carsten Egevang, Editor

Members of the QIMMEQ Project, contributing authors

reviewed by Sue Hamilton

The QIMMEQ Project was born around 2014 as a “multidisciplinary project dealing with the cultural history of the [Greenland] dog, its origins and its health.” A sense of urgency recognized many pressures resulting in a regression in the traditional use of Greenland Dogs and their alarming population decline, down by 50% over the past thirty years. Under the leadership of Professor Morten Meldgaard, a diverse international team, but based at Ilisimatusarfik (the University of Greenland in Nuuk), the QIMMEQ Project established a set of goals, including social/cultural and scientific research, engaging the input from traditional Greenland (and elsewhere) dog teamers, setting an example for future endeavors and producing and sharing the bounties of the QIMMEQ Project’s labors. These outgrowths include conferences in Sisimiut (The Arctic Nomads Symposium and its resulting workshop booklet) and Nuuk, published scientific research, public outreach through the media, a series of five documentaries and, the subject of this book review. Published in March 2020, QIMMEQ – The Greenland Sled Dog is described as “…a tribute to the sled dog and the people who use it and take care of it.” (page 13)

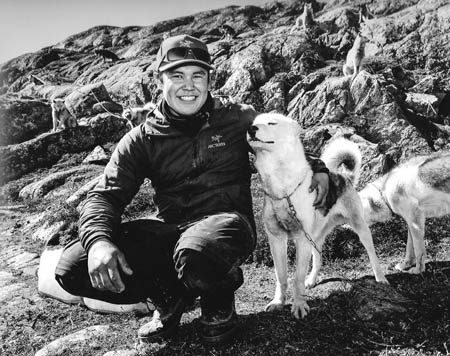

Project participants are to be collectively applauded for the impressive body of knowledge the QIMMEQ Project has generated to date. The group’s photographer/Ph.D. biologist, Carsten Egevang, could be described as the visual presence of the QIMMEQ Project due to his widely viewed extraordinary photography chronicling just about every aspect of Greenland Dogs as well as the people intimately involved with them. Just as one might recognize a well-known composer by his/her musical scores, the spectacular black and white images of arctic dogs, humans and landscapes are readily recognizable as, “Oh that’s got to be an Egevang!”

If a picture is indeed worth a thousand words then Egevang’s 149 images (most including detailed explanations), occupying 148 of QIMMEQ’s 224 pages, including nineteen two-page spreads, is in its own right a stand-alone work. The images range from expressive portraits of dogs to teams at work within an enormously vast natural backdrop, serving to demonstrate to the viewer the dramatic difference in size between landscape versus dog team. There is also no shortage of images showing the relationships between the dogs and their humans.

There are regional

differences in the ways in which dogs are used, and bred

in

Greenland, typically adapted to the physical conditions, such as the type of surface

the sleds are driven on. Mushers may also have personal preferences, which do

not necessarily have any practical significance. An example of this is Scoresby

Hammeken from Ittoqqortoormiit, who uses a team almost exclusively made up

of black dogs (page54)

Greenland, typically adapted to the physical conditions, such as the type of surface

the sleds are driven on. Mushers may also have personal preferences, which do

not necessarily have any practical significance. An example of this is Scoresby

Hammeken from Ittoqqortoormiit, who uses a team almost exclusively made up

of black dogs (page54)

The photography, however, does not simply rest on its own laurels. It serves to enrich the text of a body of work accomplished by the QIMMEQ Project since its inception. Not including the Preface offered by His Royal Highness Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark and the one hundred-and-two References, there are six sections:

These sections are further divided into many sub-headings offering the reader even more detail, such as: a symposium with impact on cultural policies and research; racing changes dog types; hunting and fishing; reasons for the decline; European contact with Greenland; sled dog genetics; relationship between polar wolves and Greenland Sled Dogs; climate, environmental poisons and diseases; feeding and keeping dogs; a professional dilemma; prospects for the QIMMEQ Project research.Introduction – Dogs of the past and the birth of the QIMMEQ Project

Arctic Nomads – Cultural exchange and dog sled building

Present Day Use of the Dog – A centuries old-tradition in transition

Origin of the Dog – Immigration and evolution history

The Sled Dog’s Health – Diseases and dog keeping

Epilogue – The Future of the Greenland Sled Dog

Very early in the book I was delighted to see Ken MacRury’s master’s thesis The Inuit Dog: Its Provenance, Environment and History acknowledged as “…probably is the most accurate and comprehensive overview of our knowledge about sled dogs so far.” (page 19). Unfortunately Ken, who self-describes doing his master’s work as a “Canadian researcher”, was mis-identified as an “American scientist”.

The book does not shy away from describing the Greenland Dog as a “tool”, not a pet, going into some detail regarding pragmatic solutions regarding sick and old dogs and other practices poorly viewed and understood by outside cultures (tourists). But throughout QIMMEQ many quotes and ten substantial vignettes of team owners explain how they admire, respect and value their dogs.

“My dogs meant the world to me. They

made me a complete human being.”

Bent Heuser, Ilulissat, February 2018 (page 124)

Bent Heuser, Ilulissat, February 2018 (page 124)

QIMMEQ does an admirable job of covering historical, biological, evolutionary, ethnological, archaeological, cultural and traditional health, implications of changes in husbandry practices, regional differences in breeding selections for various traits and mushing. I did take serious objection, however, to a comment on page 82: “The original sled dog of the Alaska region is the Alaskan Malamute.” I nearly fainted! The sentence went on to describe this dog as, “…characterized by its large size, thick fur, stamina, and physical strength, just like the Greenland sled dog.” Well of course! The dogs erroneously identified by the section authors as Alaskan Malamutes (first created in Wonalancet, New Hampshire USA in the late 1920s/early to mid-1930s using aboriginal landrace dogs in part from northwest Alaska) were in fact then called Eskimo Dogs, now Inuit Dogs. I am wondering if the significant distinctions between aboriginal landraces such as the Inuit Sled Dog as one of the first domesticates in the natural world as opposed to cultured breeds such as the Alaskan Malamute created in modern times for vastly different purposes are lost on whomever said this. I also feared that QIMMEQ Project biologists were not going to acknowledge the genetic identity of the Canadian Inuit Dog as one with their Greenland Dog. Much to my relief they did allude to that in a later section, although not as unequivocally as I would have expected.

QIMMEQ portrays a mixed picture of the future of the Greenland Dog. On the one hand it is said that due to their use in hunting, fishing and tourism “the sled dog culture is very much alive.” (page 205). On the other side of the kroner, however, is a dire need for veterinary care – vaccinations, wormings and interventions for injury and illnesses. Additional concerns have been voiced requesting that the dogs be protected from genetic contamination, have access to traditional foods and better husbandry and living conditions, and restricted use of snowmobiles for hunting and fishing.

Mushing downhill

can be a challenging experience for any musher. On steep

slopes, a heavily

loaded sled may gain speed in excess of what the dogs are able to run, and they risk getting run

over from behind. Fisherman Kim Hansen from Ilulissat hitches dogs behind the sled to avoid

risk of injury; simultaneously they help slow the sled down on the way downhill. (page 61)

loaded sled may gain speed in excess of what the dogs are able to run, and they risk getting run

over from behind. Fisherman Kim Hansen from Ilulissat hitches dogs behind the sled to avoid

risk of injury; simultaneously they help slow the sled down on the way downhill. (page 61)

QIMMEQ’s excellent photography and comprehensive text traverse enormous ground. The book has clothbound covers and interior sheets so substantial that turning one page feels more like two. The combination of content and construction define this as book of substance. But even more than this, QIMMEQ’s significance represents commitment to the Greenland Inuit Sled Dog and its associated traditions and culture. I dearly hope that it and its creator, the QIMMEQ Project, are seen as an example to emulate, to spark enthusiasm in others who have a history with aboriginal landraces, in this particular case Arctic Canada.

“As far back as I can

remember, I have been surrounded by sled dogs.

I went along on my first longer sled journey when I was two years old.

My father Hans Peter Jensen, was my first teacher, and he passed all his

knowledge of dogs and sleds on to me. Later on, my fishing buddy

Kim Hansen taught me more.” (page 69)

I went along on my first longer sled journey when I was two years old.

My father Hans Peter Jensen, was my first teacher, and he passed all his

knowledge of dogs and sleds on to me. Later on, my fishing buddy

Kim Hansen taught me more.” (page 69)

Henrik Jensen, Ilulissat, May 2019

Visit Carsten Egevang’s website for many more details about QIMMEQ – The Greenland Sled Dog including more photos (many prints can be purchased), book specifications and purchase (in English, Danish or Greenlandic) information.

The QIMMEQ Project is made possible with financial support from European Union funding; the philanthropic Velux foundation that “…supports technical and scientific research as well as environmental, social and cultural projects in Denmark and internationally”; and other public research and private foundations.