In this Post

From the

Editor: PostScript – From Famine to Feast

F.I.D.O.: From the Other Side of the World to Qimmiq Territory

Oh, those dog commands!

Dogs – One of the many reasons I loved them

Wally Herbert’s dogs – the Norwegian connection

Nansen Sledge Production

Langsomt på Svalbard (Slowly on Svalbard) Deferred for One Year

Book Review: QIMMEQ – The Greenland Sled Dog

Siu-Ling Han Memorial Scholarship

The Trip of a Lifetime

F.I.D.O.: From the Other Side of the World to Qimmiq Territory

Oh, those dog commands!

Dogs – One of the many reasons I loved them

Wally Herbert’s dogs – the Norwegian connection

Nansen Sledge Production

Langsomt på Svalbard (Slowly on Svalbard) Deferred for One Year

Book Review: QIMMEQ – The Greenland Sled Dog

Siu-Ling Han Memorial Scholarship

The Trip of a Lifetime

Navigating This Site

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Index of articles by subject

Index of Journal editions by

volume number

Index of PostScript editions by publication number

Search The Fan Hitch

Articles to download and print

Ordering Ken MacRury's Thesis

Our comprehensive list of resources

Defining the Inuit Dog

Talk to The Fan Hitch

Shop & Support Center

The Fan Hitch home page

Editor's/Publisher's

Statement

Editor: Sue Hamilton

Webmaster: Mark Hamilton

The Fan Hitch Website and

Publications of the Inuit Sled Dog– the

quarterly Journal (retired

in 2018) and PostScript – are dedicated to the

aboriginal landrace traditional Inuit Sled

Dog as well as related Inuit culture and

traditions.

PostScript is

published intermittently as

material becomes available. Online access

is free at: https://thefanhitch.org.

PostScript welcomes your

letters, stories, comments and

suggestions. The editorial staff reserves

the right to edit submissions used for

publication.

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

Contents of The Fan Hitch Website and its publications are protected by international copyright laws. No photo, drawing or text may be reproduced in any form without written consent. Webmasters please note: written consent is necessary before linking this site to yours! Please forward requests to Sue Hamilton, 55 Town Line Rd., Harwinton, Connecticut 06791, USA or mail@thefanhitch.org

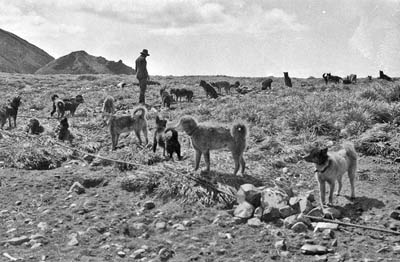

Willie Kulikowski driving the dog team called 'Kelly Gang'. Ian McIntosh is the passenger.

©Russel Marnock/Australian Antarctic Division

Oh, those dog commands!

by Bernadette Hince

I am a dictionary-maker interested in the English words of the world’s polar regions. The dictionaries I write are historical dictionaries. They are slow to write, but (luckily for me) I find them fascinating – and fun. The Oxford English Dictionary from Oxford University Press is probably the world’s best-known English historical dictionary.

I live in Canberra, Australia. This article came about when I contacted the editor of The Fan Hitch PostScript, Sue Hamilton, for advice on whether the term “span” is used in Arctic dog sledging. All the evidence I had suggest that its use is only Antarctic. She was able to confirm that it was not a term she, or others she consulted, knew from the North.

The Antarctic Dictionary

In 2000 my historical dictionary The Antarctic dictionary: a complete guide to Antarctic English was published in Melbourne by CSIRO and Museum Victoria. It includes the distinctive words used in English-speaking Antarctica – not just Australian bases, but British, South African, New Zealand and US – as well as the words of the subantarctic, reaching as far north as the Falklands, Gough Island and Tristan da Cunha, and even Île Amsterdam and Île St. Paul. Many of the terms unique to these places are natural history or science words – words like snow petrel, nightbird, lantern fish, ice krill, Tristan albatross. As far as the Antarctic continent goes, quite a few of the dictionary’s words are related to sledge dogs and travel.

Since the publication of The Antarctic Dictionary I have been making a combined historical dictionary that includes Arctic words as well as the Antarctic ones documented in the 2000 edition. Its working title is The Grand Polar Dictionary. I think I’m getting close to finishing it although, to be truthful, I have felt like this for most of the past ten years.

The capital city of Australia, the world’s driest inhabited continent, might seem a strange place to be researching polar words, but Australia has a long history of Antarctic involvement from the time of Carsten Borchgrevink (or Borchgrevinck) and Henrik Bull, and before Bull’s expedition the southern voyages of navigators such as James Cook and James Clark Ross.

In the early 20th century, sledge dogs were also used in the small region of mainland southeastern Australia which has winter snow cover, as this Mt Kosciuszko (then ‘Kosciusko’) photograph below shows:

‘Eskimo dogs (used in Antarctic Expeditions) at the Hotel Kosciusko, New

South Wales, Australia, sled pulled by huskies, ca1900 – ca1925.’

glass lantern slide, gift of SJ Jones

source: State Library of Victoria

Rich resources are now available online for researchers. The National Library of Australia, located here in Canberra, also has strong polar holdings. I was able to supplement my local research with periods at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK with its unbeatable polar library, and a few short research trips to a number of subantarctic islands (the French islands of Amsterdam, St. Paul, the Crozets and Kerguelen, New Zealand’s Snares, Antipodes, Auckland and Campbell Islands, and Australia’s Heard/McDonald and Macquarie Islands) and to Antarctica (Davis and Casey stations, alas, not before the removal of the dogs and some of the historic huts of the Ross Sea region). As many if not all The Fan Hitch readers will know, under the Madrid Protocol all dogs were removed from Antarctica by April 1994 making any Antarctic dog-related terms historical from that date onwards.

“Ah”

Like the Oxford English Dictionary, the polar dictionary I am working on has quotations for every word, as well as definitions. One example is the word “ah”, a sledge dog command used in the Arctic and (formerly) Antarctica.

The earliest use in print of “ah” is in SK Hutton’s Among the Eskimos of Labrador (1912), where he says:

Towards noon a man ahead of us shouted “Ah” at the top of his voice, and every driver took up the cry. All the dogs stopped and lay down of one accord … Julius suddenly said “A-ah”. The dogs lay down very willingly.Twenty-odd years later in Antarctica, the British Graham Land Expedition was also using the command. A. Stephenson writes in John Rymill’s 1939 book Southern lights: the official account of the British Graham Land Expedition 1934-1937:

As soon as Fleming shouted “Ah!” and the team came to rest, Riley pounced on Nanok before he had a chance to remember he was not in harness.And in 1953 F. Spencer Chapman says in Watkins’ last expedition:

We used the Angmagssalik words of command which the dogs were supposed to understand: ... A very high-pitched Ille! Ille! Ille! to go to the right, and a deep, nasal Ai! to make them stop.But while in Antarctica where “ah” meant only ‘stop’, the command can also be used to mean not ‘stop’ but ‘go!’. In the Arctic, D. Howarth writes about a Greenland experience in the 1957 book The sledge patrol:

He calls to the team to go – “Ah, ah” – and cracks his whip.As you can see, there is some confusion about the meanings of dog commands. In addition, sometimes in the process of being transferred from northern to southern hemisphere, the meaning seems to get blurrier.

‘Dogs tethered out on Macquarie Island 1911’

photographer Douglas Mawson

source: State

Library of New South Wales, Australia

“Auk”Take another word, “auk” (which is also spelt eeyuk, ouk and yuk). In a 1953 issue of Polar Record (vol. 6 no. 45) Raymond Adie records that “auk’”means ‘turn right’:

Turn right “Auk, Auk” (“au”

pronounced as “ou” in loud).

The New Zealand Trans-Antarctic Expedition’s newsletter of October 1956 also noted:

“Yuk” for a right-hand turn.

Sometimes, though, “auk” means the opposite. In Shelagh Robinson’s Huskies in harness: a love story in Antarctica (1995) Rod Ledingham says:

I was given a team called the Picts, and shown the commands: the one for left was ‘auk’.This is confusing, especially if you are supposed to be clarifying the meaning of words, which is what most people think dictionary-writers ought to do. As it turns out, I’m not the first person to have had trouble untangling dog commands. In a 1957 Polar Record (vol. 8 no. 56), RJF Taylor said:

The actual words used on F.I.D.S. have been standardized. To turn left is Irr-r-re, to turn right Auk. Croft gives the Eskimo words as Ille for right and Yuk for left, i.e. there has been a transposition of these words when they were anglicized.Perhaps the confusion over the meanings of these and other dog terms is not news to The Fan Hitch readers. It is probably an area where there are many variations anyway. Maybe there are almost as many variations as there are individual dog drivers. Trying to pin down a shouted command which can probably be heard in many different ways is also difficult. At any rate, it has been for this dictionary-maker. So if you should have any helpful thoughts, or examples that you think might help me to sort things out, I would love to hear from you. My email address is: coldwords@gmail.com.

Thumper, lead dog of the BAS Husky team the Huns, with Rupert Summerson

photo Rupert Summerson, Adelaide Island, Antarctica 1981

Bernadette Hince is a dictionary-maker and historian. Her PhD thesis concerned the environmental history of seven subantarctic islands. She has also worked on dictionaries of Australian and New Zealand English.